What resources are needed in order to enter into mentoring relationships?

Mentoring as Practice

- [2025]

- Nora Sobbe

How are mentoring relationships initiated?

What role do differences in experience play in this form of relationship – or can they be understood as peer-to-peer encounters?

How does group mentoring differ from one-on-one mentoring situations?

How do mentoring relationships relate to other social forms such as friendship, partnership, or (chosen) family? Could mentoring perhaps be understood as a conversational mode that friendships, partnerships, and other relationships may temporarily adopt? Or does mentoring extend beyond the moment of speaking?

Do mentoring relationships serve a broader purpose that exceeds the one-on-one encounter?

The project Mentoring as Practice introduces a note-spitting machine (a machine, which spits out small pieces of paper with short text inputs) to people currently engaged as mentees or mentors, as well as to those interested in starting a mentoring relationship. Mentoring is a vessel for learning/teaching, often part of everyday study life at art universities. Students are accompanied by a mentor in developing their projects, with the mentor responding to the topics or projects the mentee brings to each session. The exact way of working is usually left to the individuals involved, making mentoring a format that raises the question of how and in what constellations we want to learn together.

As a mentee, I often was not fully aware that, with each mentoring session, I was actually involved in shaping how mentoring could unfold; instead, I found myself questioning certain interactions in terms of how well they aligned with my preconceived notions of what mentoring is meant to be. I realized that unspoken and undiscussed assumptions about the mentee/mentor relationship may limit how we experiment with different ways of learning as mentees/mentors.

This finding motivated the development of a note-spitting machine that initiates an exchange between various mentee/mentor constellations by circulating statements, questions, gestures, and methods. The machine accompanies mentoring sessions, spitting out notes randomly toward mentee or mentor and prompting both to reflect on and discuss their preconceptions of mentoring. A feeding station invites mentee and mentor to feed the mechanism with findings from their own exchange, which will inform upcoming mentoring sessions.

The project questions whether a structuralization of mentoring sessions might help to hold the openness of mentoring as a learning format and invite mentees and mentors to shape/enact mentoring as a practice.

Kann eine punktuelle Formalisierung von Mentoring-Sessions Gestaltungsspielraum öffnen?

note-spitting mechanism

concept object: Nora Sobbe realization object: Johannes Reck, Marcel Rickli photo: ©Marcel Rickli

HOW THE NOTE-SPITTING-MACHINE WORKS:

The object is positioned during mentoring sessions between mentee (A) and mentor (B) and spits out notes at defined time intervals (within a random range) in the direction of A/B. The notes contain utterances/questions/gestures/methods. A or B is invited to read the note aloud to their counterpart in several ways: as an offer for interaction; by distancing themselves from it and thereby updating the mentoring setting as it exists; modifying it in contrast to the slip of paper; and so on. A feeding station is crucial for the setting, where the pool of statements and questions from which the object randomly selects is generated. Mentees and mentors are invited to type on a keyboard utterances/questions they would have liked to say/ask in a mentoring session to note actions waiting to be realized within a mentoring session (“I actually wish I had recorded the conversation.”) or to note actions/gestures that could become a method (“I brought strawberries from my neighbor’s garden, just take some!”). The notes are digitally saved and can be assigned to either A or B, or they are saved under the category “A/B”: here the object randomly decides whether the statement/question will be spat in the direction of A or B during upcoming mentoring sessions. The note-spitting machine draws on the digital storage that is generated by mentees and mentors at the feeding station.

WORKSHOP WITH THE PEERS OF THE 25/26 SCHOOL OF COMMONS COHORT:

During the School of Commons Gathering from July 4–6, I collected slips of paper with the peersof the 25/26 cohort for the note-spitting-machine. It was one of the first opportunities to generate notes for the spitting mechanism. In a roughly 50-minute workshop, we simulated mentoring sessions in which the note-spitting object was involved in an adapted form.

I asked the workshop participants to form groups of three. Each group member briefly introduced a topic or project they were currently working on and would like to explore further through discussion. In the next step, each group selected one of these topics or projects. The person who had proposed the chosen topic became the mentee, while the other two negotiated who would take on the role of note-taker during the conversation and who would act as the mentor. For approximately 30 minutes, participants were then invited to discuss the mentee’s topic, or, in the case of the note-taker, to document the conversation. The mentee could express in advance any preferences regarding what the notes should focus on.

To involve the note-spitting-machine in this setting with several mentoring sessions of three-person groups, it was necessary to adapt the way the object functioned, since it existed and currently exists only in a single version and cannot participate in multiple mentoring sessions simultaneously. I therefore positioned myself next to the spit mechanism, and every time the mechanism would have stuck out its tongue and spat out a slip, I projected a note labeled “Mentee:” / “Mentor.” Additionally, a small auditory signal was needed to draw the mentee’s and mentor’s attention to the “spat-out” slip. The mentee and mentor could then decide whether to integrate the statement/question/method/gesture written on the slip into their conversation or to distance themselves from it.

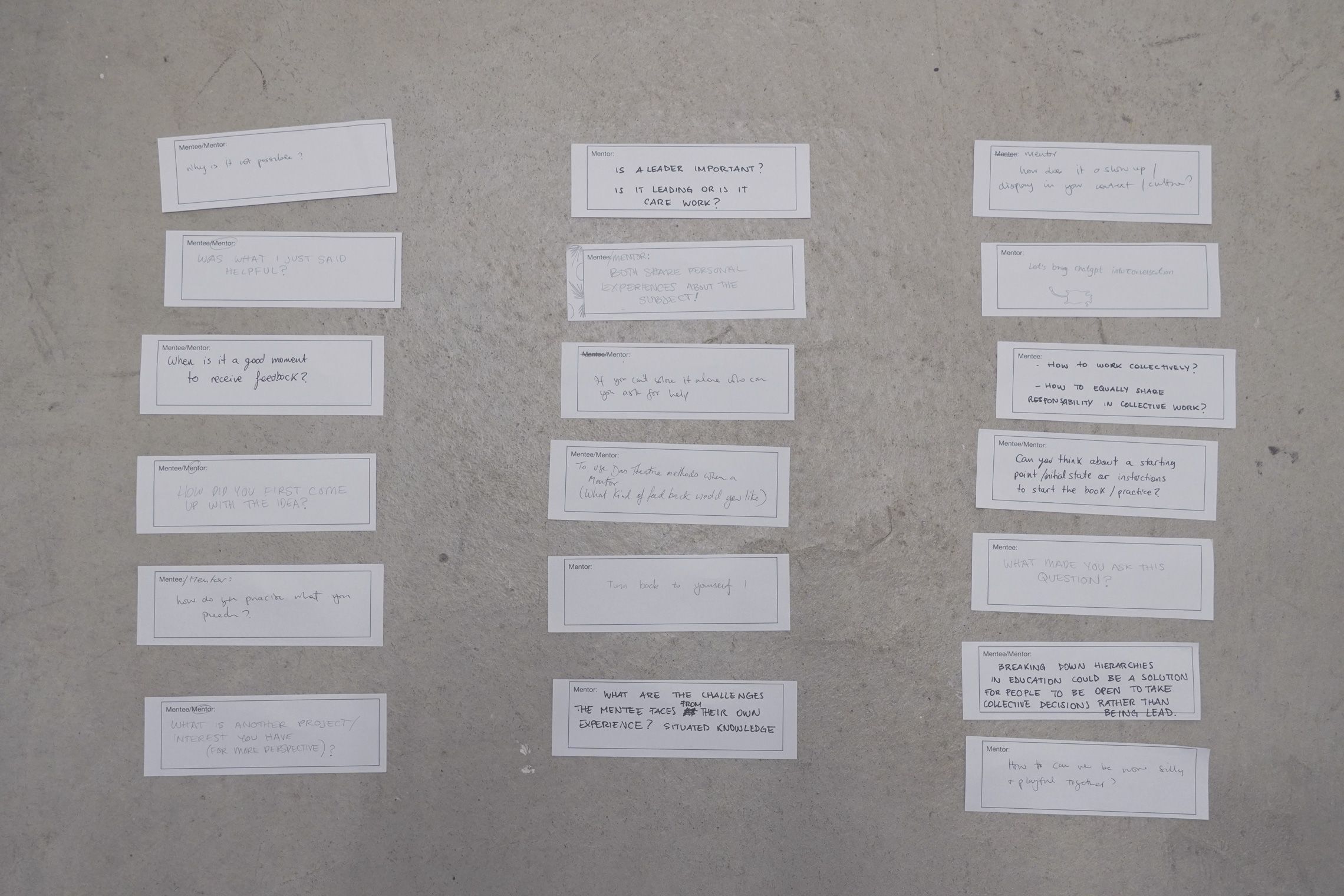

At the end of the workshop, the groups were asked to use the final ten minutes to write down statements, questions, methods, or gestures that could inform future mentoring sessions:

Mentor: How does it show up/display in your context/culture?

Mentee/Mentor: Why is it not possible?

Mentee: How to work collectively? How to equally share responsibility in collective work?

Mentor: What are the challenges the Mentee faces from their own experience? Situated Knowledge

Mentor: Is a leader important? Is it leading or is it care work?

Mentor: How did you first come up with the idea?

Mentee: What made you ask this question?

Mentor: Was what I just said helpful?

Mentor: Turn back to yourself!

Mentor: Let’s bring ChatGPT into conversation.

Mentee: You could form a silly research/mutual aid group.

Mentee/Mentor: How do you practice what you teach?

Mentor: How can we be more silly + playful together?

Mentee/Mentor: Both share personal experiences about the subject!

Mentee/Mentor: Can you think about a starting point/initial state or instructions to start the book/practice?

Mentee/Mentor: When is it a good moment to receive feedback?

Mentee/Mentor: To use DAS Theatre methods when a Mentor (What kind of feedback would you like).

Mentor: What is another project/interest you have (for more perspective)?

notes collected within the SoC Cohort 2025/2026

Nora Sobbe

Nora reacts to specific social situations through object-design processes that invite exploration of social interactions which may initially feel familiar.

SoC Gathering, 2025

04.07.2025 — 06.07.2025

Reflecting on the SoC Gathering this past week at Zurich University of the Arts. Find out more

SoC Assembly 2026

05.02.2026 — 08.02.2026, Thurs 15:30–18:00 | Fri 15:00–18:00 | Sat 10:30–13:00 | Sun 11:00–13:00 / 15:00–17:00

SoC Assembly 2026: Programme Find out more