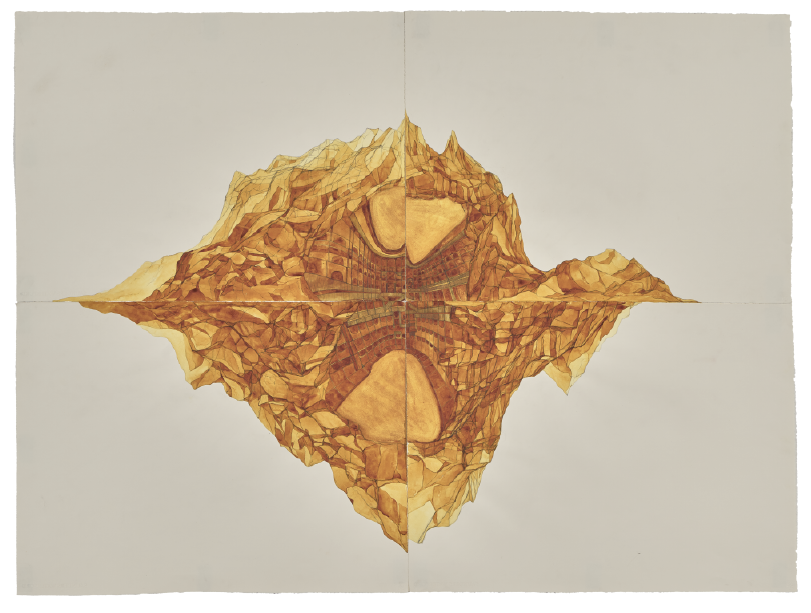

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi. End of History II, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

I initially began this project planning to only speak with arts editors, thinking of them as the perfect meeting point between artists, curators, writers and readers. But when I started my interviews, I was luckily to speak with two ineffable individuals who made me think differently (as editors do) about knowledge production. Doing academic work, I think about this a lot but often from within the confines of an academic institution. For this project, I wanted to get outside of this structure, to think about both art and climate differently.

One of my first interviews was with Bukola Oyebode, a writer, editor and publisher. She is the founder and editor-in-chief of art magazine The Sole Adventurer (Nigeria). Initially a blog about contemporary Nigerian art, the publication became a fully-fledged magazine in 2018. Published online and in special print editions, it now covers art from across Africa and the diaspora. Oyebode’s many projects include the TSA Master Class, facilitated by Chika Okeke-Agulu, award-winning art critic and professor of art history at Princeton University.

Oyebode explained that the Master Class was set up not just to establish more critical voices in the art scene, but to connect older generations art critics and historians with young art writers. She emphasised the huge disconnect in the flow of history between different generations of arts writers, a problem seldom addressed by institutions, like universities or galleries, more focused on the practical business of studying, making or selling art, and not as attuned to pedagogy in a communal sense. This simple, but important, observation reminded me of an essay by artist Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, “Radical Sharing”. In it she confesses her self-doubt when asked to give a keynote address on a panel devoted to knowledge production, worried that she did not know enough about it to speak confidently on the topic. “Like much else in today’s world of hyper-specialization, knowledge and discussion about the means of its production seem to belong to experts, academics, other intellectuals, not me.” This perception of knowledge as the domain of those more senior or educated is pervasive across epistemes, from scientific climate studies or arts criticism.

Nkosi’s essay first unpacks and defines knowledge, knowledge production and sites of knowledge production because as she observes, “calling something knowledge can be a political act, even a radical one”. She then presents a range of artistic strategies for widening the scope of what we consider to be knowledge, for widening the scope and reach of ideas to a common benefit. “Radical sharing always has inclusivity as one of its aims. Radical sharing privileges the power of human interaction of creating community of deep listening, of sharing ownership of really seeing one another. There is a sense of agency invoked in at of radical sharing.”

She also asks ”What place might radical sharing have within dominant sites of knowledge production, institutional settings with established hierarchies and power relations? This was the question on my mind when I spoke with Danielle Bowler, Culture Editor at New Frame (South Africa), a not-for-profit, social justice media publication, dedicated to pro-poor, pro-working class well-written and well-illustrated journalism that is accessible and jargon free. New Frame is editorially independent and all editorial decisions are made by the editors in conjunction with our reporters and photographers. Having worked with Bowler before, I have personal experience of how intentional she is about thinking through all of the many dynamics involved when working with both writers and arts, but having her articulate her own ethos behind this was especially illuminating.

She explained that of course all writing can be artistic but culture writing can really lend itself to that, through the process and form, so in a sense the work of editing is also a form of curating, after all, even the act of making a reading list is a site of curation. She referred to an incredible interview with curator Renee Mussai who discusses exhibition-making as “a creative, generative ‘doing’ activity – dialogic, and activist at its core… the desire is to create a visceral experience – yet one that is at once emotional, intellectual, political, personal, sensual – that is felt in the body and the mind, and hopefully, proves restorative and transformative for/to some… encourages different ways of seeing, thinking, and being – even if only temporary – and invites us to reflect and think critically about our core values, the changing worlds we live in, the historical conditions that have shaped us… and to imagine possible futures and different modes of futurity.”

Thinking about modes of futurity in the layered practices of both editing and curation, Bowler explained that the desire to centre a feminist ethic in her work led to thinking about care work in art or, the ethics of care. This awareness and commitment to a particular ethos in the everyday practices is quite similar to Nkosi’s suggestion that moments can be sites of knowledge production – shaped by an ethic and a politic. Mussai also discusses “the communion between art and activism – its disrupting power, if you will – and in the transformation and activation of space(s).”

Here, Bowler’s focus on the importance of language, not just in the literal sense of the words in texts, but in moments (like when sending emails) or sites (like the culture desk of a publication) is critical. This is especially relevant when trying to articulate vast planetary questions about changes to earth-systems. As a starting point, Bowler explains that with language at the heart of curating written work, applied creative practice can and should be about learning with every piece. Thinking with, through and towards a deeper understanding of the work being written about, whether that is climate report or an exhibition review. These conversations with Oyedobe and Bowler (not to mention the reading they led me to) really opened up my thinking about the flow of history and sites of knowledge curation. And this, ideally, is what deschooling is all about.

Click below for the next text, 4. Dialogic processes, decolonial pedagogic practice and humanizing history, which investigates dialogic processes and decolonial pedagogic practice in curation and publications.

Sindi-Leigh McBride

Researcher and writer from Johannesburg, and a PhD candidate at the Centre for African Studies, University of Basel.

4. Dialogic processes, decolonial pedagogic practice and humanizing history

Conversation with Nomusa Makhubu and Nkule Mabaso, curators Read more

2. Communicating without aestheticizing or academicizing

Conversation with Angela Chan, creative climate communicator Read more