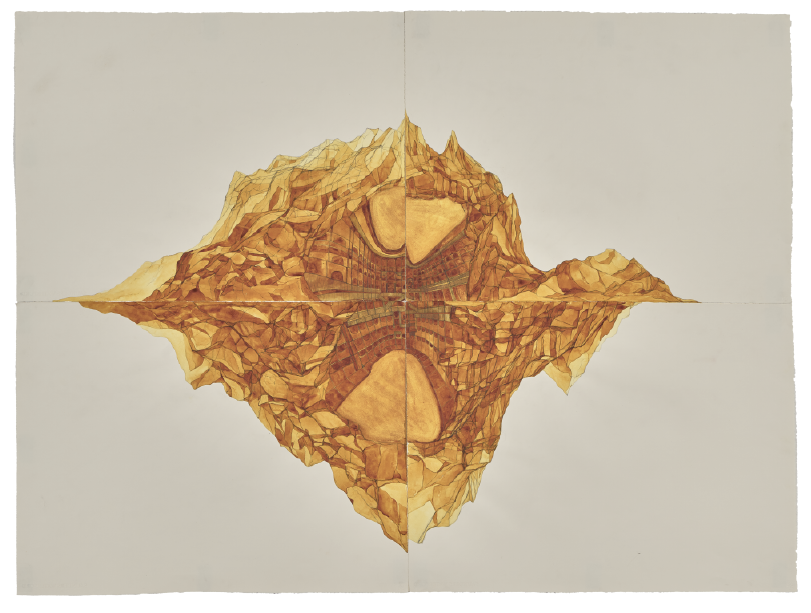

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Singer, 2014. Mixed media on paper. Courtesy of the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg.

4. Dialogic processes, decolonial pedagogic practice and humanizing history

03.01.2021

I recently wrote about artist Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s use of volcanoes, exploring them a way of linking geology with ecology, the physical with the ephemeral, the objective with the subjective. This was an opportunity to think about how the entanglement between aesthetic (understood as embodied, sensuous encounters with Nature) and art (understood as imaginative visualisations of Nature) are inextricably part and parcel of knowledge production. In her most recent exhibition Battlecry (2020), Sunstrum volcanoes help to imagine concepts like deep time that are outside of the realm of human experience, help to abstract human context to think with angry rock formations, help to engage with art as a way of knowing—even when we really have no idea what is happening, deep down below the lithosphere. Even though it is well established, recognised and theorised that art production is knowledge production by virtue of being a cognitive act, the lines between art, science, and activism blur and sometimes a landing point (like a volcano) is useful for detangling the interdisciplinary boundaries between the arts, humanities, social sciences and geosciences. Some of the questions that preoccupied me while writing that piece live on in this project, questions about ways to adopt interdisciplinary reading and writing approaches to art and questions about mechanisms for communicating and critiquing environmental risk, education and debate in visual arts

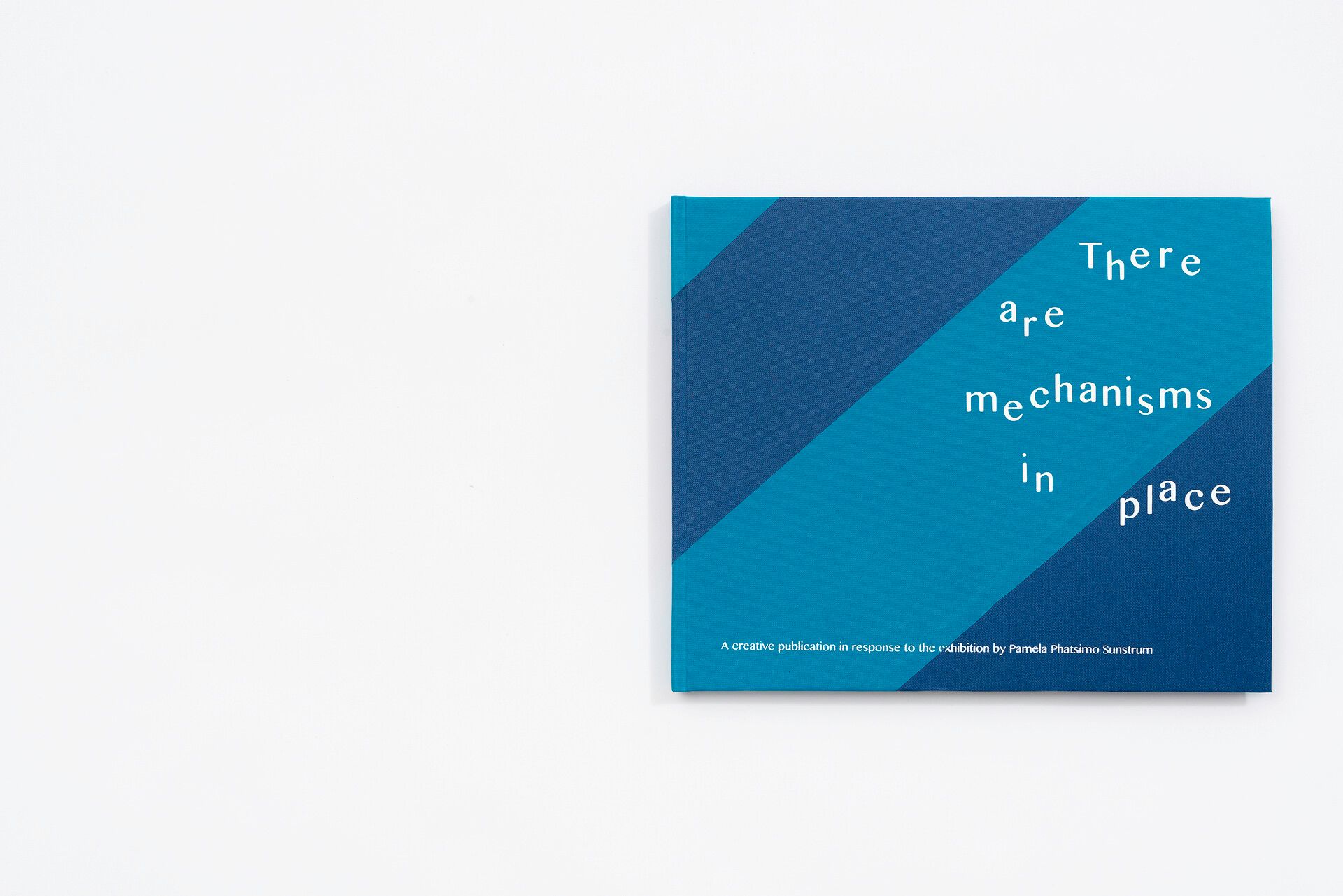

In this sense, the collaborative spirit of There are Mechanisms in Place (2020), a response to Sunstrum’s practice was a huge inspiration. Nkgopoleng Moloi cogently describes the publication as a sacred text on the basis of how it offers discursive tools, makes meaning of ambiguity and shapes visions of liberation, “The publication does not simply explain the exhibition, but rather offers alternate engagements through dialogue, interruption, assembling and gathering”.

Cover. Courtesy of Natal Collective.

“The exhibition and the creative publication are both ways of thinking together without being limited by expectations – it is a way to explore, to engage – it is a space to be. It is a moment, a convergence and a point of departure.”

In the introduction, curators Nomusa Makhubu and Nkule Mabaso explain how Sunstrum’s work and the creative responses to it in the publication foreground histories; illuminate the significance of spatial politics; detail the disorientation and delirium of postcolonial, post-apartheid, neoliberal society; explore the depths of memory entrenched in landscape, and how ideas of the sublime can take us beyond how we conceive of scientific nature; and investigate the intersection of science and technology in the alternative geographical space proposed by the work.

Still thinking of moments as sites of knowledge creation, I spoke with Makhubu and Mabaso about their work and the process of putting together the creative publication. Nkule Mabaso is an artist and curator, currently curator at the Michaelis Galleries at the University of Cape Town. Recent projects include the curation of the South Africa Pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2019, Venice together with Nomusa Makhubu , associate professor of Art History and Visual Culture at Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town. Both teach art history and write as academics, and do “most of the exciting work in collaboration.” This focus on collaboration guided much of our conversation, as Mabaso explained that, “there is a long history of heroizing a single curator, but curating is inherently collaborative and we see out work as part of an intellectual dialogue that has a lot to do with how we are developing themes and ideas and concepts through our curatorial work and publications.”

Makhubu then expanded that much curatorial collaboration is not entirely horizontal, either resulting in collaboration with artists or institutions in ways that give rise to difficult hierarchies that they try to avoid by working with artists and writers “more laterally, less vertically, as equals to expand the conversation, without interest in individual ego to make room for more generative conversation.” Laughingly, she suggested that “there are too many heroes” a reference to the wit behind Dear History, We Don’t Need Another Hero (2018), curated by Gabi Ngcobo for the 10th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art. This exhibition “confronted the incessant anxieties perpetuated by a wilful disregard for complex subjectivities”, and like the Tina Turner song that the title references, rejected the seduction of saviour narratives, instead thinking and acting beyond art, and “refusing to be seduced by unyielding knowledge systems and historical narratives that contribute to the creation of toxic subjectivities.”

Toxic subjectivities abound in climate change, from denialism to green colonialism. But a potential salve is to be found in how both Makhubu and Mabaso stressed the importance of the dialogic processes guiding their curatorial work and publications: “we didn’t just want another exhibition catalogue. We wanted natural engagement with what was on display instead of just writing a review: to take the moment as a catalyst to express a response through one’s own practice. In this way, a dialogic exhibition was accompanied by a dialogic publication free from toxic subjectivity.

View of Nkule Mabaso. Visual essay. Courtesy of Natal Collective

We spoke briefly about decolonial pedagogic practice, and while both admitted to never sitting down and going, “okay now its time to do decolonial work”, they recognise the pervasive nature of coloniality in the institutions that they work with which makes it important not to just say things about decoloniality but to find ways beyond it to generate different knowledges about agency, ways of humanizing how we work and relate to each other. Thinking and doing, being empowered in practice, beyond rhetoric. Decolonial pedagogy is embodied too: one part of you might be well-versed in theory but another part needs to ask “how does this become part of the work without needing to announce ‘okay now I am wearing my decolonial hat’?” It’s about going, “now I am working so how do I, and my ideas, fit into this understanding of broader systems? How do I work with people who share my ideas or don’t , while maintain the integrity of those ideas?”

Ngcobo described the aim of the 10th Berlin Biennale as being to produce “a plan for how to face a collective madness” and Makhubu and Mabaso’s approach to curating might just be that plan. Unpacking the title of their exhibition at the Venice Biennale 2019, they explain that

“The stronger we become is a way to think about social resilience. People create coping mechanisms under harsh socio-economic conditions. Being resilient not only means being strong, but also means being pliable. However, the persistence of divisive plutocratic politics, means that people continue to be stretched to a point where they can no longer take it. The rise in global movements against social injustice is a sign that we have to think more carefully about resilience and the will to resist. With this exhibition we are acknowledging the climate of cynicism and disillusionment. We are also acknowledging what it is that makes us fully human, in the context of a dehumanising history.”

This focus on collaborative humanizing isn’t something that can easily be theorised or methodologized, in either the sciences or the arts. But in this moment, this project, this site of knowledge production, Makhubu and Mabaso’s work is ineffable and instructional, to say the least.

Read the next text 5. Mineralizing land and fabulating climate (see related below) which introduces the idea of climate consciousness as fabulation.

References:

Khan, S. (2020) “Curating as World-Making – An Art on Our Mind Creative Dialogue. Journal of African Cultural Studies Volume 32, 2020 – Issue 4

Krivane, E. (2018) “Interview with Gabi Ngcobo” On-Curating. Available here

Leibbrandt, T.(2019) “Venice Biennale 2019: In conversation with curators Nkule Mabaso and Nomusa Makhubu” Artthrob. Available here

Sindi-Leigh McBride

Researcher and writer from Johannesburg, and a PhD candidate at the Centre for African Studies, University of Basel.

3. Knowledge production as radical sharing and curation as care

Conversations with Bukola Oyebode and Danielle Bowler, editors Read more

2. Communicating without aestheticizing or academicizing

Conversation with Angela Chan, creative climate communicator Read more