Fostering Learning Environments for the Future

School of Commons (SoC) is a ten-month programme and community-based initiative situated within the Zürich University of the Arts with a strong commitment to the exploration and advancement of self-organised knowledge production1. Despite taking its form as a School, SoC stands apart from traditional educational structures in that its content and direction are not predetermined by a fixed program or curricula. Instead, they are shaped by the collective know-how, ways and workings, aspirations, and curiosity of its dedicated communities. This approach garners a collaborative, communal spirit that runs throughout SoC’s programme and learning environments, creating a dynamic that allows for fresh perspectives, innovative ideas, and a continuous evolution of knowledge exploration and distribution.

Projects that have taken part in SoC are hugely varied in their form, approach, and vision. Over the eight years of its existence, SoC has welcomed projects focussing on alternative housing models, (ultra) translation, language production, LARPing, alternate worlding, expanded publishing, teleportation, and learning from fungi and forests, just to name select examples2. Though the projects that shape SoC straddle the scope of research and practice, all are united in their endeavour to learn from, share with, and exchange as part of commons-informed learning environments, amongst diverse peers and publics.

Despite the malleable structure of the School of Commons, certain core infrastructures inform, maintain, and uphold the learning environments, which, in turn, allow for unexpected encounters, new connections, and evolving directions to unfold and flourish within each cohort. Moreover, these infrastructures lay the basis for the two central components that compose the SoC learning environments, the first being the notion of “peer learning” and the second being “commoning practices”. This article is an exploration of the core infrastructures and methods from which the learning environments, based upon the principles of peer learning and commoning practices, have been maintained and reproduced. The examples will be examined both through the lens of the theoretical frameworks from which these environments are grounded, as well as the core methodologies that have been developed through active ways and workings brought to life through the day-to-day activities, and programmatic structures within the SoC learning community.

SOC LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

School of Commons produces, and is, in turn, produced by multiple forms of learning. The learning environments themselves can be understood simply as digital, physical and satellite in their form. The main programme offering and exchange of SoC is facilitated digitally, using video technology and digital meeting infrastructures for connecting and exchange. This is used in combination with collaboration focussed tools such as Etherpads, Miroboards, Zoom and Discord, which are considered core methodologies for alternative ways and workings in and of themselves. The emphasis on digital learning environments as the basis for SoC is paramount, as it ensures access for participants anywhere in the world. Each year, in correspondence with the selected cohort, differing time zones, meeting schedules and digital meeting offerings are assembled to ensure maximum participation accessibility. The digital toolset builds upon the accessibility further by ensuring the programme can incorporate and honour different languages, registers, modes of participation, communication and expression.

The physical learning environment of SoC is mainly based around the Zürich University of the Arts, Switzerland where each cohort gathers twice a year for an “intensive weekend” of sharing and exchanging, and an “end of year assembly” for making public the processes, progress, and findings of the research projects. These public and semi-public exchanges usually take the form of exhibitions, workshops, town halls, walks and lectures. Alongside the University Campus, public spaces, bars, cafes and off-spaces are activated for walks, talks, drinks, parties, talks, and other encounters that sit outside of the “official” programme of School of Commons, but are just as influential to the ways and working of participants’ individual and collective processes. The satellite learning environments of SoC take place across different countries, cities and contexts, around the world. This includes satellite programmes as companions to the bi-yearly Zürich meetups. Examples of which have previously taken place in Chile, South Africa, Costa Rica, the Netherlands, and Germany.

The satellite learning environment also encompasses the alumni network of School of Commons which expands far beyond the confines of the ten-month programme. The growing School of Commons alumni network is an active and engaged community who continue to build upon their knowledge and connections garnered during SoC, to visit, meet up, exchange and plan programming outside of the current SoC activities.

SOC CORE INFRASTRUCTURES

Each learning environment within the overall structure of SoC is in turn made up of both tangible and intangible infrastructures that inform their ways of working, and the shape and form they take. The use of infrastructural frameworks for understanding these specific learning environments within SoC takes inspiration from Susan Leigh Star’s interpretation of infrastructures as a “fundamentally relational concept, becoming real infrastructure in relation to organised practices”3. This approach very much aligns with SoC’s learning environments form of practice-based learning built upon relationality, and relation-based knowledge production and dissemination. This viewpoint is enhanced by Lauren Berlant’s description of infrastructures in The Commons: Infrastructure for Troubling Times, as “the movement or patterning of social form. The living mediation that organises life: the lifeworld of structure”4. “Lifeworld” seems particularly apt as it encapsulates how infrastructures are alive: active, malleable, and adaptive substrates, that are always in response to new information, inputs, and adaptation in accordance with evolving needs and requirements.

The importance of infrastructures as frameworks for more tangible learning formats is emphasised in Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space, where Keller Easterling explains that infrastructures act as binding mediums in organisations, structures, and environments. He states “Infrastructures determine the conditions under which we live our lives and give us a deeper understanding of the world. Infrastructures allow the movement of people, goods, of information. They offer the ground on which systems operate and services are offered”5. This is combined with a deeper understanding of infrastructures as “embedded”, invisible, ephemeral relations that take place within a learning environment, as described by Erik Klingenberg, who conveys infrastructure as “sunk into and inside of other structures, social arrangements, and technologies.”6

SoC has also developed learning environments based on a series of select infrastructures that inform how the learning environments are made, creates spaces and relations, and behave. It is through the workings of these infrastructures that certain inherent outcomes of the SoC learning environments take form and shape. For instance, safe spaces, strong relational connections, confidence for participants to choose process over progress methodologies, renewed approaches towards experimentation, the unknown, and systems of unlearning with their practices. The first infrastructure in which SoC bases its learning environments upon is affective infrastructure; infrastructures based upon an understanding and appreciation of the importance of affect in establishing relations with one another, and choosing how we wish to live and be in the world. Sara Ahmed demonstrates in Affective Economies that affect can be understood as a condition, a reaction, an embodiment of feeling and/or desire that is cognitive, proprioceptive, behaviour and psychological7. Affect can be felt, transmitted, responded to through language, gesture, facial recognition, voice, posture, and recognition of emotion8. Affect as an infrastructural form is further strengthened by Lauren Berlant, who states, “affective assemblages are what bind us to each other and to the world itself. They are an invitation to study and practise different forms of persistent togetherness or ongoingness. Ways to keep in, and with, these messed up, troubled times”9. Affective infrastructures showcase acts or “structures of feeling or desire”, desire for different ways of being together, of working together and ways of understanding the world. Affective infrastructures place feeling and memory at the forefront of their operationality, as well as their methods of doing, ways of producing and organising. They question how imaginative, living infrastructures can accommodate multiplicity and difference, mobilise bodies, and build new worlds. One of the main ways in which affective infrastructures appear throughout SoC is in the “process over outcome” ethos and methodology. From the point of application to the final assembly, no expectation is placed on participants to produce or provide a set outcome or result.

Instead, the emphasis is placed on process, understood by new connections, insight, and perspectives, in turn new ways of imagining and enacting how to be together, how to exchange, how to work together, and what knowledge feels, looks, sounds, and smells like.

One of the ways in which these often ephemeral processes are documented is through the Ways & Workings (W&W) directory10. Ways and Workings is a methodology developed by School of Commons which assembles and amasses the various themes, methods, and environments that are essential to forming spaces of learning and knowledge. W&W function as navigational tools that seek to connect various sites of work, practice, and research. In turn creating a broad, alternative, multidimensional directory of how to work together, how to work within and around dominant, often oppressive, systems, and how to imagine knowledge, distribution, research, and practice, otherwise. The Ways & Workings acknowledged and activated in the directory are typically informal, against-the-grain, and alternative in their approach.

Another example of capturing these processes and affective infrastructures is through the multiple publishing channels that flow through SoC. Each project is provided with a dedicated digital publishing space to share, through text, video, audio or otherwise, moments, findings, and challenges in their process trajectory. Each year the collective digital publication ISSUES is compiled that seeks to document some of the changes, challenges, questions and ways and workings participants have developed through their projects, but also as a cohort11. These are combined with key milestones throughout the programme such as “Kitchen Sessions”. A dedicated time and space where each project are invited to share not only their project and interests, but the context from which they are researching and practising. The Kitchen Session is a safely facilitated space where room for unlearning, not-knowing is facilitated, academic or artistic vulnerability and fragility can be engendered in a way that is encouraged and supported.

The second infrastructure which forms the core of the SoC learning environments are care infrastructure. Care infrastructures seek to resituate the personal, the public and the political in relation to one another, in turn building new relationship models. These infrastructures work through the “collective”; through exchange, sharing and togetherness, as opposed to the individual, or through set power hierarchies. Researcher and curator Sascia Bailer states, “to care is to be co-dependent, to extend and share resources, knowledge, and to feel commitment and solidarity. A central ethical principle in our social infrastructures”12. Care infrastructures call for structural vulnerability and fragility, and dedicated spaces to build values and experiences of trust, support, self-worth, and recognition. They ensure that wellbeing and support are at the core of all operations, in combination with, as theorist and curator Daphne Drago states, “the need to care critically, to care with and for each other”13.

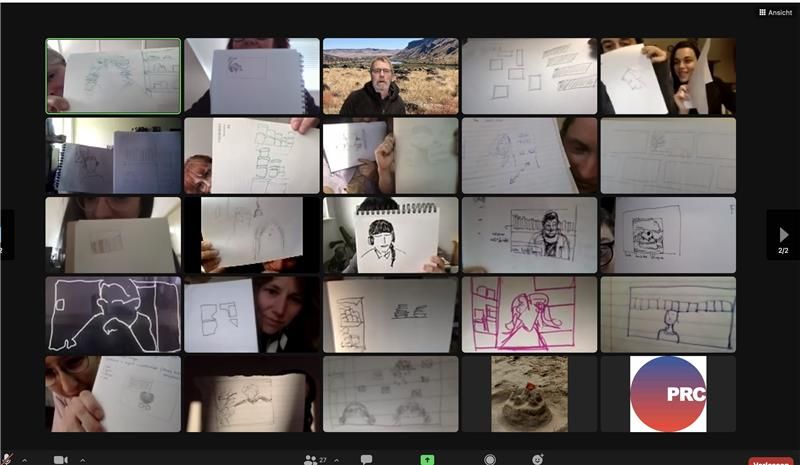

A smaller scale, less tangible, yet no less integral method for harnessing care infrastructures through the duration of the SoC programme is through the check-in and check-out methodology that begins and ends each collective meeting and/or public session. These check-ins range from drawing other participants in the room, to singing together, to joining somatic and breathwork exercises. Through the repetition of always entering in and leaving the digital space in this way a sense of safety, cohesion and calmness is garnered, as well as fostering connectivity and relationality.

An example of a SoC check-in moment. Participants are asked to select another participant in the room, without telling them, and spend 10 minutes drawing them. All participants reveal their drawings at the same time.

A more tangible example, and one of the earliest for each programmatic cycle is using a Care Rider. A dedicated form that each participant is required to fill out to share, with their permission, access needs, preferred communication styles, preferred programmatic structures, and the level of (self) organisation and accountability that will allow them to thrive within the programme. Alongside the Care Rider, SoC offers small one to one session which introduces the Care Rider as an apparatus, and examples of what could be included, as, for a Care Rider fulfil its care function, it must be accessible to those who wish to complete it.

The Care Rider is combined with further protocols that uphold care-based values of SoC. These can be found in a dedicated code of conduct, codes of participation, which emphasise that the act of participation can take many shapes and forms, depending on the needs and capacity of the individual, including the right to leave at any point. Moreover, alternative forms of documentation and access to information and knowledge production are provided as aftercare for most meetings and events: through alternative transcriptions, recordings, email summaries, and extra meetings, to ensure that it can be accessed later or from afar.

Perhaps one of the more overt infrastructure layers with SoC is commons infrastructure, understood as the dynamic of assembling, especially with a basis built on social practices, modes of sociality, and ways of defining social, ecological, and planetary relations. Commons infrastructures are not only based on sharing and exchanging, for instance with resources and knowledge, but also on the acknowledgement of difference and conflict. In this sense, they can be dialogical, experiential, as well as a lens for critique and affirmation as much as a method for resistance and creation. In The Posthuman Glossary Lindsay Grace Weber states they “should be understood as constant emergence, of commons social, economic, and environmental relations and practices. They are spaces of experimentation for both theorizing and practicing, providing a lens for critique and affirmation and a method of resistance and creation”14.

Within SoC, commons infrastructures are present across many levels. Firstly, through the active dismantling of the teacher/student dichotomy. This is encouraged through the open exchange sessions during the planned Kitchen Sessions, as well as the multiple open spaces for self-organisation which are placed throughout the programme. During on-site weekends together each project is invited to participate with a workshop, walk, talk, performance, or otherwise, of their choosing, in which others in the programme attend. Beyond this planned programme of workshops and events, open spaces are left for experiments in collaboration and participation to merge. When such moments occur, the barriers between the knowledge “giver” and the workshop “attendee” start to become remixed. For all programming, SoC offers the 3/3 model: one third offering/giving, one third being offered/taking, and one third free space to encourage unexpected and spontaneous connections and collaborators. This model demonstrates that not only can every student be a teacher, and vice versa, but given the appropriate facilitation and space often dynamics are assembled where these roles can be both embodied simultaneously and entirely dismantled. This dismantling of the teacher/student dichotomy is further strengthened with the active dissolution of disciplinary silos throughout the programme. This is actively championed by connecting projects and people through curiosities and interests, rather than specific skill-sets or disciplinary backgrounds.

An example of an open Kitchen Session, a presentation of what Open Learning can look like in different contexts.

A further core commons infrastructure within SoC is the commitment to “making public”. Making public is a programme trajectory that encompasses apparatus such as the annual digital publication ISSUES, dedicated publishing blogs, the Ways and Working trajectory, public events, and public podcasts. Making Public is thus the action of reproducing the knowledge, know-how and methodologies, brought to, formed within, and circulated amongst the SoC environments, outwards. Be that to the cohort, to alumni, to publics, and much further beyond. With consent, all that is produced within SoC, be that an etherpad workshop exercise, a publication, or a radio broadcast, is made public through the different digital and physical tools that are circulated as part of the programme and infrastructure. Knowledge is treated as a material and immaterial resource that, once identified, and activated, becomes porous throughout and outside of the structures of SoC. In doing so, becoming connected to and expanded upon by relevant groups and communities with similar curiosities.

To specifically discuss conflict and difference management, a core component of commons infrastructure. The SoC Code of Conduct acts as the primary basis for how modes of communication and behaviour are expected to be enacted. Beyond this, sessions dedicated to individual and group feedback, meditation and conflict resolution are accessible to participants throughout the entire programme, alongside dedicated moments after key-milestones for larger-scale feedback to be shared. Moreover, all participants have access to dedicated one to one feedback and check-in sessions throughout the year where topics such as accessibility, conflicts, and barriers are regularly addressed and, if required, discussed.

The final infrastructure of note is social infrastructure, PEER LEARNING which runs along the intersections of differing socialites, and can be found within the complex combinations of objects, spaces, persons, practices, and principles within a given environment and in particular social relations to one another. Essentially, social infrastructures form the foundations of how we interact and how we gather. Dedicated spaces and structures are therefore vital for channelling social infrastructures and for strong social infrastructural bonds, relationships, and behaviours to be nurtured. In Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization and the Decline of Civic Life, Erik Klingenberg states that social infrastructures is one of the main factors for engendering social cohesion as, “social cohesion develops through repeated human interaction and join participation in shared projects, not merely from a principles commitment to abstract values and beliefs” 15.

The social infrastructure within SoC naturally appears more overtly during the longer physical get-togethers positioned throughout the programme. These include the Intensive Weekend at the midpoint of the programme in June where participants can share and show their “process”, and any results they wish to disseminate, or challenges they would prefer to ruminate on, and the end of year assembly where these are made public. These moments have made pre-planned social infrastructures as part of their setup and structure: exchange-based workshops, knowledge circulation, and participatory events, and planned collective free time. What is perhaps more pertinent is that it is the more unplanned “between'' moments that more affective social infrastructures come to life. Acts of cooking together, staying in the same accommodation, walking together between locations, and cleaning together creates a social fabric of connections and collaborations.

Alongside natural occurrences of social cohesion, there are also more meditated moments throughout the programme, too, where the SoC team take on a more facilitation-focussed role. The most obvious of these moments is the kick-off weekend, facilitated digitally. During the kick-off weekend each project is invited to share a little about their work and context, as well as some of the questions they wish to explore, or challenges they are either already, or foresee facing. Through these presentations, always followed by a dedicated open question and response session, a networked correlation of curiosities and interests, problems and pathways begin to emerge. From this social information, the SoC team begins to suggest, sometimes expected, often unexpected connections. Further dedicated spaces for crossover and connection are then facilitated through focus groups, group check ins, and “extracurricular” activities such as reading groups, writing groups and yoga sessions, where cohesion is notably strengthened.

Within the SoC learning environments there are clear links between each of the above infrastructures, as rather than being standalone substrates, they work best when informing one another, as part of a networked infrastructure of togetherness, or, as infrastructural design engineer Louis Bucciarelli understands it, a “dense interwoven fabric”16.

A further important element to consider when examining infrastructures in relation to the SoC learning environments is that although infrastructures and subtracts enact, inform, and perpetrate all forms of organising and organisational methods, infrastructures are used and upheld by people, and, therefore, by access. Infrastructures are not separate to or from us. They are implemented, maintained, and reproduced by those who sit within their structures and systems. Therefore, alongside the implementation of such infrastructures there also needs to be the assurance that first, they are accessible, and, once so, are maintained, cared for and, if appropriate, reproduced by those affected by and affecting them. This is why SoC always understands its community and publics not only as being integral to the maintenance of the core learning infrastructures, but as part of the very infrastructures themselves.

A performance and working during the SoC Intensive 2022 on Street games of Our Childhoods

PEER LEARNING

This series of infrastructures come together as the basis for the two key components that together form the SoC learning environments. These come under two main categories: peer learning and commoning practices. Peer learning has emerged as a powerful educational method that harnesses the collective knowledge and experiences of learners, placing them at the centre of the learning process. It recognizes that individuals have a lot to gain from engaging with their peers, fostering collaborative and interactive environments that promote deeper understanding, critical thinking, and personal growth. At its core, peer learning involves the active engagement and participation of learners in a reciprocal exchange of knowledge, skills, and perspectives. Rather than relying solely on traditional teacher-student dynamics, peer learning encourages learners to become both teachers and learners themselves, creating a symbiotic relationship where everyone benefits from the shared expertise within the group.

One of the fundamental principles of peer learning is that learners are uniquely positioned to support and challenge one another. By working together, sharing ideas, and providing feedback, peers can offer multiple perspectives and diverse approaches to problem-solving, encouraging a deeper exploration of concepts and fostering creativity. This collaborative process helps learners develop critical thinking skills, enhances their communication abilities, and promotes a sense of ownership over their learning journey.

In peer learning environments, learners can engage actively in the construction of knowledges. Through discussions, group projects, and cooperative activities, they can deepen their understanding by articulating their thoughts and engaging in meaningful dialogue with their peers. This interactive process encourages reflection, as well as the exploration of different viewpoints. In turn nurturing a sense of empathy and respect for others' perspectives. Moreover, peer learning provides a supportive and inclusive learning community. It creates a space where learners feel comfortable expressing their ideas, seeking assistance, and learning from their peers' experiences. This collaborative approach fosters a sense of belonging, increases motivation, and encourages learners to take ownership of their education.

Peer learning also has numerous benefits beyond the academic realm. It cultivates important social and interpersonal skills, such as active listening, empathy, and effective communication. By collaborating with peers from diverse backgrounds, learners develop cross-cultural understanding, tolerance, and appreciation for different perspectives. These interpersonal skills are invaluable in preparing individuals for the complexities of the professional world and in broader society.

The peer learning structure of SoC, which centres curiosity-driven research and practice, life-long learning, and interdisciplinary approaches, establishes a community of practitioners in which reciprocal exchange, openness, and a friendly atmosphere are the main ingredients to social cohesion and successful peer-centred collaborations. Participants are the central part of the larger whole within the SoC structure, in which their presence is both valued and necessary. The aim of this peer learning structure is to develop a programme that is open to all, making the knowledge and practices that arise from our labs publicly available. Collaborations are encouraged between different age groups, disciplines, and (educational) backgrounds. Participants are encouraged to take ownership and authorship of their programme experience and knowledge pursuits, either by organising and hosting events themselves, or by inviting guest speakers and tutors that are relevant to their research. The role of SoC is to support and help organise the educational programme their participants would like to experience. In this sense, a needs and requirements offering is provided, where the peer learning structure directly responds to the peers which form its core.

The outcome of this specific kind of learning structure can be witnessed through the entangled mutual support systems, cross disciplinary collaborations, process-oriented focuses, and non-linear research and practice trajectories that emerge year after year. The approaches, process, outcomes and needs and requirements that materialise from the participants themselves then continuously feed into the peer learning structure that defines the directions and focuses SoC takes each year.

COMMONING PRACTICES

To speak of the “commons” within School of Commons, it is first useful to provide the basis for the terminology and model that commons, and commoning practices provide to institutions and structures like SoC. The commons has been understood as the shared use and management of resources by and for a community. Intrinsic to the existence of a commons is a sharing of governance, a sense of communal belonging, co-operation among community members or commoners, and a deepened sense of societal responsibility 17. Community activist Karl Linn believes that when sufficiently sustained, “commons offer spaces of experimentation and encounter that can be personalised to meet the needs of their individual community.”18In this respect, commoning can be recognized as a guiding principle of organisation, a strategy for assemblage, and the embodiment of coordinates for maintaining community relations.

Historically speaking, the commons is by no means a new concept. With an etymology dating back to the British feudal living of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the direct link between commons, land and ownership has continued ever since19. This being said, the 1960s saw a particular resurgence of use of the commons framework in a bid to oppose the advancing neoliberalization of governments that was being experienced during this period. From 1960 onwards discussions surrounding the commons become mainly associated with economics and governance, especially in scholarly discourse, following the publication of Garrett Hardin’s influential essay The Tragedy of the Commons. Hardin’s publication mourned the overuse of natural resources and the subsequent accelerated enclosure of common pool resources20.

Partly as a response to Hardin’s pessimistic approach, economist Elinor Ostrom issued a series of works examining the ways in which commons were seen to be flourishing around different parts of the world21. In her publications she attempted to forge feasible frameworks and guides for successfully, and sustainably, reproducing these examples of successful commoning. Ostrom’s work gained both scholarly and popular attention after she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009, sparking another wave of interest in the economic and societal relevance of the commons. Such a resurgence was especially apparent during this period due to coinciding with the repercussions of the European financial crash.

More recently, the commons has come to also be understood in relation to methods and spaces which facilitate the mutual exchange between aesthetics and politics and as a method of raising awareness of social ecologies of the individual, the collective and the institution22. Therefore, despite established scholarly attention on material commons, the frequent referencing of knowledge commons, digital commons, network commons and creative commons is becoming visible, suggesting a considerable shift in contemporary understandings of the concept. This is supported by Michael Hardt and Anthony Negri, influential theorists on the relationship between commons, ideologies and governance, who argue that the “common” is now not only limited to natural resources, but also contributes to the production of language, knowledge, codes, information, emotion and affect, proving immaterial commons to be an essential a resource in the resistance against neoliberal agendas23.

By considering commons as a composite term that encompasses the political, economic, social, and cultural, we can understand “the commons” within a framework such as a “school” is one in which the environments both enable and distribute resources around art, culture, knowledge and language.

Through these common spaces of experimentation, learning and encounter ecologies of care, through collaborative and cooperative means, transform knowledge production into something for and of “the common”, rather than being protected and privatised.

To establish a commons as part of any given environment or structure, three key components are required: the commons (resources), commoners (people, a community, a group) and commoning practices (the act of sharing said resources with said people)24. Commoning practices thus centre methods approaches which aim to facilitate the equally accessible management and distribution of a set of resources, within a given community. Commoning practices within learning environments therefore work with alternative models of openaccess distribution, non-hierarchical practices, and co-creation, collaboration, and relationality focused methods.

Within the SoC learning environments commoning practices work across multiple trajectories yet are always in direct connection to one another. They are at times formal, at others informal, and, moreover, can be both material and immaterial in their representation. The knowledge that can be produced and shared as part of these actions and practices is broad and entangled in its scope: tacit knowledge, inherited knowledge, lived experience, context-specific know-how are just as vital to the commoning within SoC as the establishing and remixing of theoretical, pedagogical, scientific, artistic or philosophical propositions. Commoning can take the form of a newly acquired tool for accessibility, an alternative form of participation or exchange, in the sharing of a reading list, supporting during workshops, teaching a new recipe to cook together during an in-person gathering. However, commoning is also a change in perspective, understanding or imagining of what it means to work together, to be together, to know and to do, demonstrated through the many Ways and Workings that have been assembled over the eight years of SoC’s existence.

It is through the large scale, identifiable commoning activities, such as public workshops, cross-cultural collaborations, open-source documentation, publication contributions and ways and workings activations that the commons is seen within SoC. Yet commoning is also visceral experience through the smaller scale, humdrum activities. Through the smaller and the larger scale, the visible and invisible, the interwoven commons fabric of SoC upholds larger structures of peer learning, learning infrastructures and learning environments that together, produce a global, ten-month community-based programme based around active, ongoing, continuous notions of commoning.

CONCLUSION: LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS FOR THE FUTURE

Through its learning environments, infrastructures, and apparatus of peer learning and commoning practices, School of Commons has composed a clear framework for producing alternative structures for knowledge production and distribution. To look towards the future of learning environments, and how they can continue to adapt and evolve, the answer lies simply, yet in varying forms, in accessible. First and foremost, in ensuring that programmes like SoC, but the many others that are also endeavouring to offer alternatives to formal education systems and traditional pedagogical structures, are accessible to the many, and not only the select few.

Moreover, one of the ways in which learning environments can continue to strive towards access is ensuring they remain critical, open, and adaptive to the changing needs, desires, and requirements, and to both support and reflect the communities, contexts and society they seek to serve. In tangible terms, this requires room for reflection and growth, as well as space for new ideas, experiments, and tryouts to take place. A key component to peer learning and commoning structures is precisely this space to learn and unlearn, to try and to fail, but to ensure it is being enacted in a safe and supportive structure. With specific learning environments like those of SoC, a certain degree must be handed to the peers themselves to choose and dictate the direction they want to take, not only for their cohort, but for the future iterations that will follow.

Accessibility can also be understood in terms of replicability and reproduction. The programme and self-organised curricula of SoC is open access, with most knowledge structures and outputs produced being publicly available. Yet available doesn’t always equate too accessible. Features like the W&W Directory is an activation of such resources to provide access to the methodologies, approaches and environments that are created and circulated as part of the programme. The hope is that others can take inspiration either from individual W&W, or the larger structures created in combination with the many other uses of the programme to produce other learning environments and infrastructure that respond to differing contexts, demands, urgencies, and desires.

All the core components that form learning environments like SoC: infrastructural frameworks, peer learning structures, commoning practices, and accessibility, are in a constant state of flux. They are actions, conditions, apparatus’ to be strived for, and adapted towards, and never a permanent state. Learning environments both present and the future must have an acute awareness towards this, and to understand it is the people and the communities that form within these environments that make up these layers, and it is for them and their present and future wishes to which all of these layers and components must remain committed and responsive to.

[1] About – SoC. (2023, October 16). https://schoolofcommons.org/

[2] Labs – SoC. (2023, April 26). https://schoolofcommons.org/program

[3] Star, Susan L. The Ethnography of Infrastructure. Boundary Objects and Beyond, 2016, 473-488.p.380

[4] Berlant, L. (2016). The Commons: Infrastructures for troubling times*. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(3), 393-419. p.1

[5] Easterling, K. (2014). Extrastatecraft: The power of infrastructure space. Brooklyn. Verso Books. p.7

[6] Klinenberg, Eric. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. Danvers: Crown, 2018. Palaces for the people p.32

[7] Ahmed, S. (2004). Affective economies. Social Text, 22(2), 117-139. p.119

[8] Ahmed, S. (2004). Affective economies. Social Text, 22(2), 117-139. p.119

[9] Affective Infrastructures: A Tableau, Altar, Scene, Diorama, or Archipelago - A conversation with Marija Bozinovska Jones, Lou Cornum, Daphne Dragona, Maya Indira Ganesh, Tung-Hui Hu, Fernando Monteiro, Nadège, Pedro Oliveira, Femke Snelting https://archive.transmediale.de/ content/affective-infrastructures-a-tableau-altar-scene-diorama-orarchipelago

[10] "Ways & Workings – SoC." Last modified November 2, 2023. https:// www.schoolofcommons.org/waysworkings.

[11] School of Commons issues. (n.d.). School of Commons Issues. https://schoolofcommons.org/making-public/issues

[12] Bailer, S. (2020). Sascia bailer: Curating, care and Corona. p.32 [

13] Affective infrastructure. (n.d.). creating commons. https:// creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/tag/affective-infrastructure/

[14] Lindsay Grace Weber, “The Commons” in Braidotti, R., & Hlavajova, M. (2018). Posthuman glossary. London. Bloomsbury Publishing. (2018) p.85

[15] Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. Danvers. Crown., p.27

[16] Bucciarelli, L. L. (1988). An ethnographic perspective on engineering design. Design Studies, 9(3), 159-168. p.131

[17] Karl Lin Commons and Community in Gmelch, George, and Petra Kuppinger. (2018). Urban Life: Readings in the Anthropology of the City, Sixth Edition. Long Grove, USA: Waveland Press. p.9

[18] Karl Lin Commons and Community in Gmelch, George, and Petra Kuppinger. (2018). Urban Life: Readings in the Anthropology of the City, Sixth Edition. Long Grove, USA: Waveland Press. p.9 [19] Bruyne, Paul D., and Pascal Gielen. (2011). Community Art: The Politics of Trespassing. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Valiz. p.4

[20] Surhone, Lambert M., Miriam T. Timpledon, and Susan F. Marseken. (2010). Tragedy of the Commons: Garrett Hardin, The Commons, Diner's Dilemma, Enlightened Self- ‐Interest, Population Control, Inverse Commons, Common Heritage of Mankind. London, England: Betascript Publishing.

[21] Hess, Charlotte, and Elinor Ostrom. (2011). Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice. Cambridge. Mit Press.

[22] Braidotti, Rosi, and Maria Hlavajova. (2018) Posthuman Glossary. London. Bloomsbury Publishing. p.83 [23] Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. (2009). COMMONWEALTH. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. p.4

[24] Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the Commons. Cambridge. University Press.

EXCERPT

1. Despite taking its form as a School, SoC stands apart from traditional educational structures in that its content and direction are not predetermined by a fixed program or curricula. Instead, they are shaped by the collective know-how, ways and workings, aspirations, and curiosity of its dedicated communities.

2. Within the SoC learning environments there are clear links between each of the above infrastructures, as rather than being standalone substrates, they work best when informing one another, as part of a networked infrastructure of togetherness.

3. Commons infrastructures are not only based on sharing and exchanging, for instance with resources and knowledge, but also on the acknowledgement of difference and conflict.

4. It is through the large scale, identifiable commoning activities, such as public workshops, cross-cultural collaborations, open-source documentation, publication contributions and ways and workings activations that the commons is seen within SoC.

Amy Gowen

Since 2023, Amy has been part of the leadership team at the School of Commons, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste (ZHdK), overseeing the Publishing and Public Program. In 2024, she was appointed Deputy Director.

School of Commons

Global community-learning space.