Fire is Scary: Translating Sound and Image

‘...There is always mistranslation because a translation can never be a perfect rendering from one space or one language to another. It is bound to be somewhat misunderstood, as we are all always misunderstood in every dialogue we undertake...There is no perfect transparency.’ -Stuart Hall 1

Sol wrote a short poetic text combining her two diary notes from one day. Her translation began with choosing words or sentences and detaching them from her personal experience. The following process of language translation from Korean to English gave more chance for the text to expand its meaning. But try communicating in quotes to a new supervisor, or factoring literary coping mechanisms into funding applications and you will quickly see that.

On the very morning of the 18th of March 2019, I'd had a bizarre dream, so I wrote it down in half-sleep, then the Utrecht shooting* incident happened, which was very near my house. I scrabbled about the experience and my feelings towards it at night. Later, I decided to write a new text using two writings of that day as material, wondering how much or what kind of personal traces would remain if I treated them as sets of words or sentences and try not to involve myself in it.

The first translation step happened in choosing words and sentences, weaving them together to create another story. Even though I wanted to exclude a particular event, my emotions, conditions and the specific people in the dream from original writings, I still had a reason to choose those diaries. I thought, what is the core thing I wanted to deliver from them. I challenged myself to make the new text's atmosphere resemble my diary notes by using only declarative sentences, tried to remove adjectives and adverbs from the selection process, although there were unavoidable exceptions.

When I translated Korean to English, numerous choices, hierarchies within, distortions, reconstructions happened as always. It is a similar process from weaving writing style, however much more limited since language has less space that I can intervene. I wanted to show the language translation process in the text and my hesitation in it. So, I left a few traces in the text.

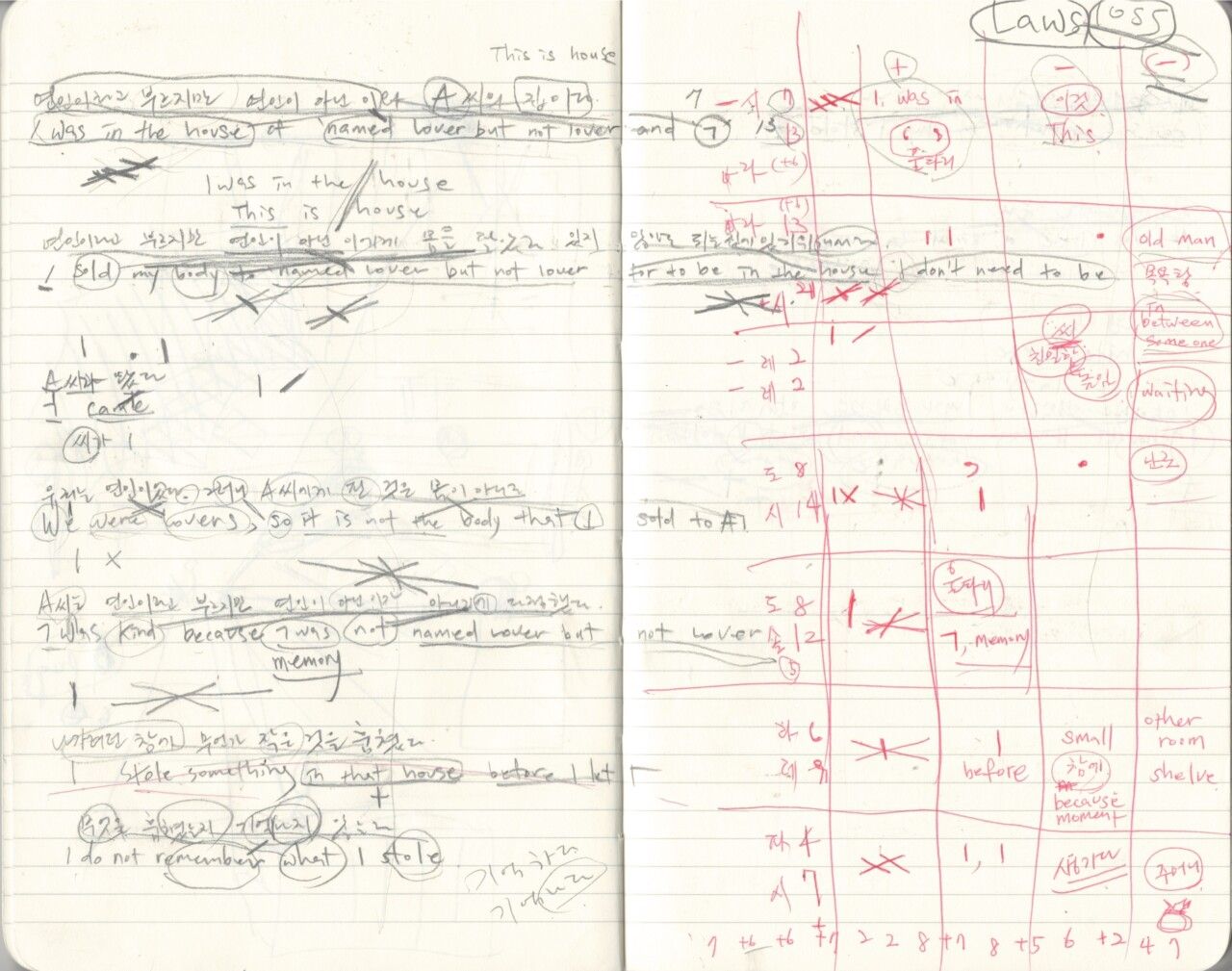

Fig1. analyzing the process of translation - Korean to English

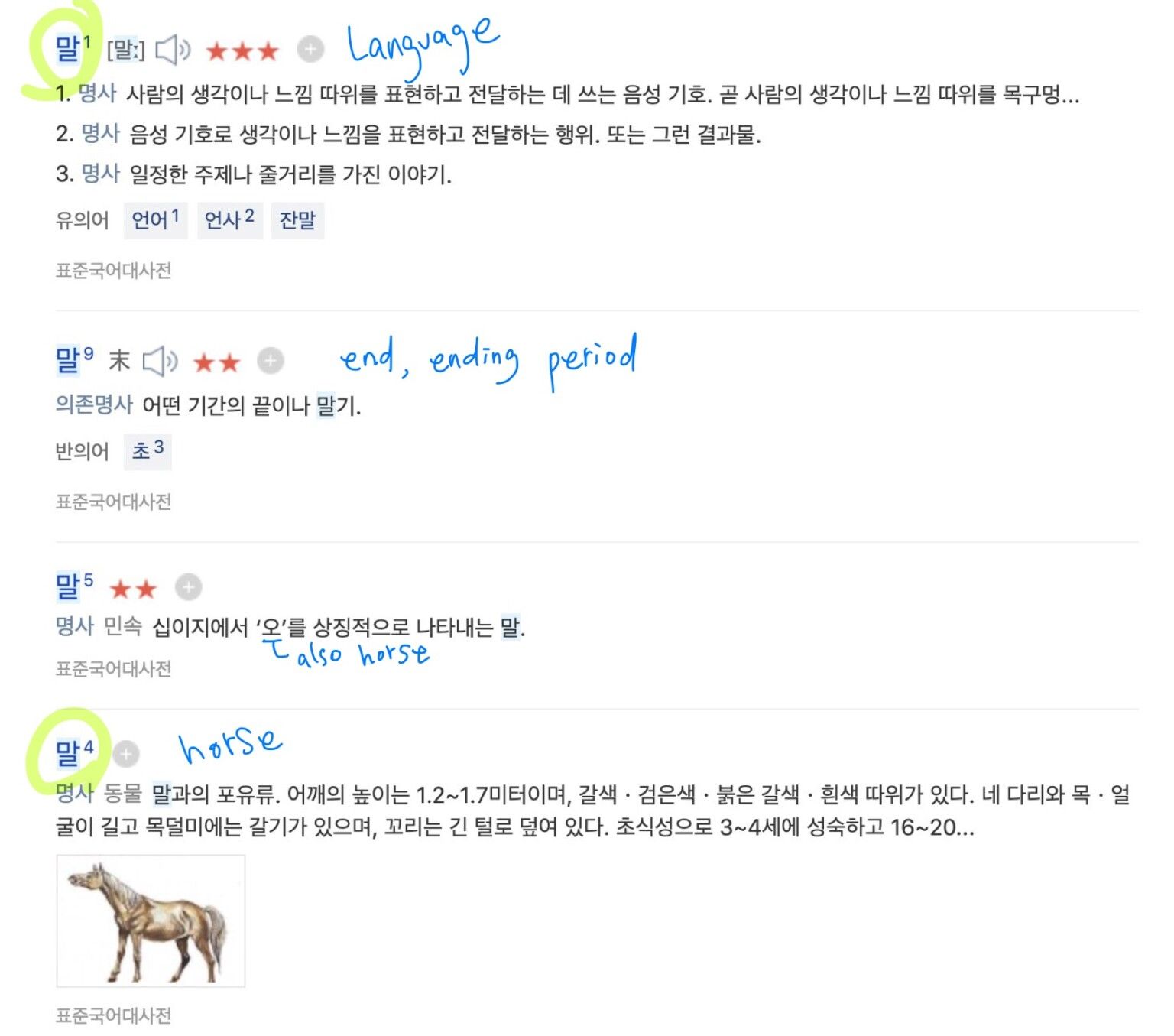

For example, 'language' and 'horse' came from a homonym Korean word '말'. Using those two words as the translation for '말' made more sense since my task was ignoring my first intention in words and seeing them as material.

Fig2. word '말' in dictionary

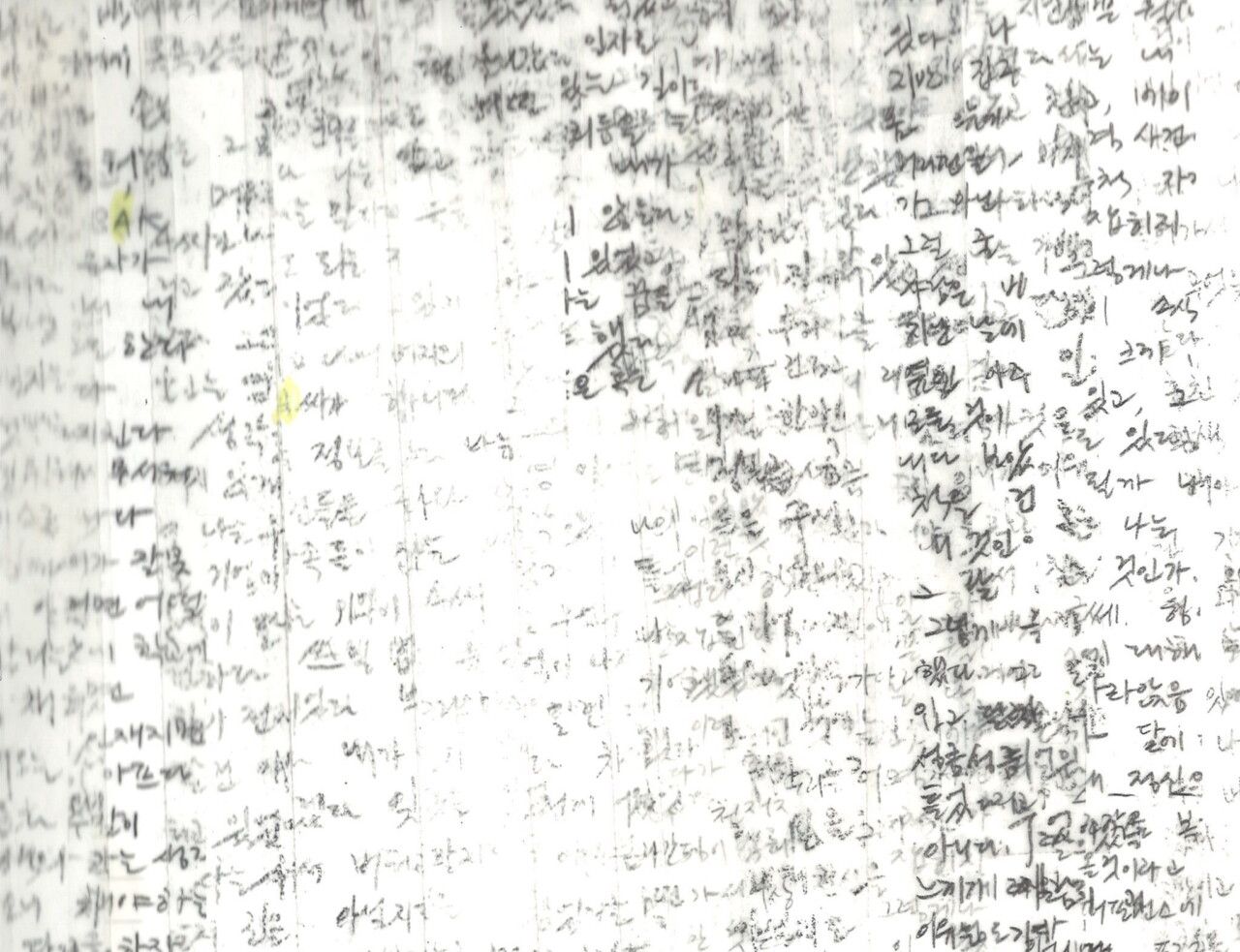

As my practice starts from writing and I move away from the mother tongue, translation has become inevitable. However, translation is not only applied to language. Because of my position, working within space brings translation issues surrounding different media. The first try of translating Fire is Scary text materially for a pop-up show was making visual copies of my handwriting from the diaries using clear tapes. Because of the random manners of sticking on and off the tape's width, the writing became cloudy.

Fig3. the first tiring of Fire is Scary text to visual material - (partial view)

‘...translation operates by exceeding the narrow meaning of language. A novel is translated into a film, just as a political idea can be translated in action... Translation passes through and circulates in the intervals of different instances of meaning, threading together discontinuous contexts.’

- Naoki Sakai

Gordon transferred the cloudy, dreamlike atmosphere of Sol’s text into written music. He used open harmonies and wandering melodies, above layers of shifting flows of time to recreate the essence of the text in the form of a song cycle.

The process of translating the Fire is Scary text into music occurred over the course of two years (2019-2021). I first came across Sol’s text as an installation work in a pop-up exhibition and I was immediately drawn it. The formatting especially caught my eye - parts of the text made use of Korean Hangul (letters), some words were stacked on top of each other, and other words were highlighted in yellow. I found myself wondering how these effects could be recreated in the form of music.

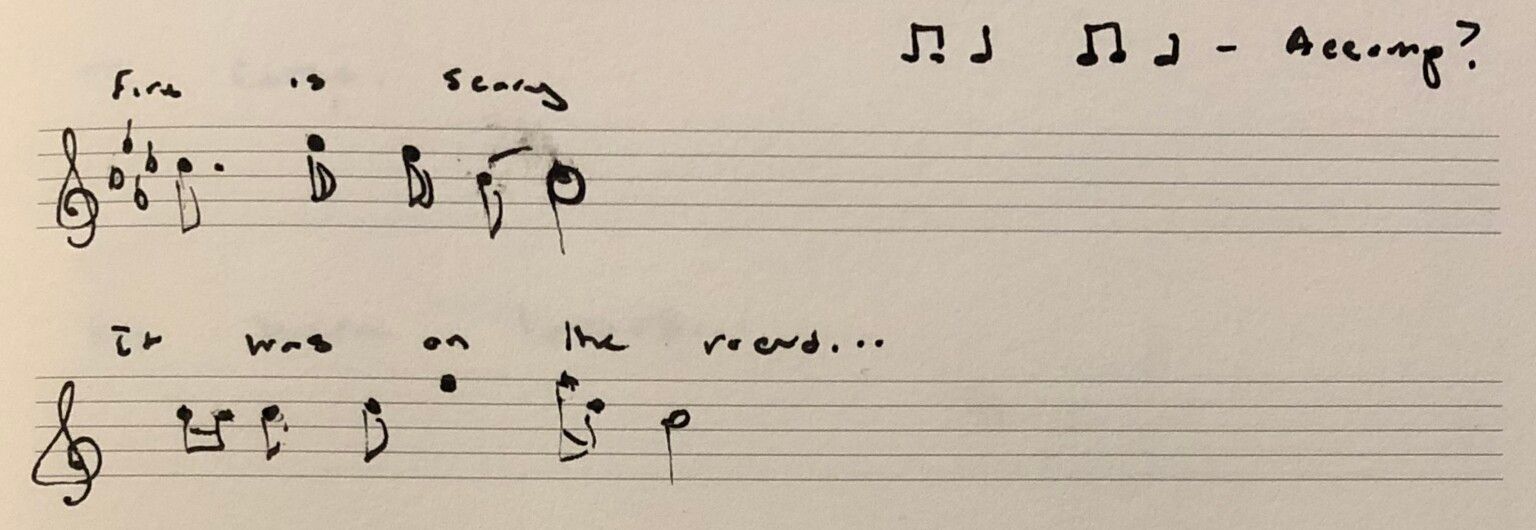

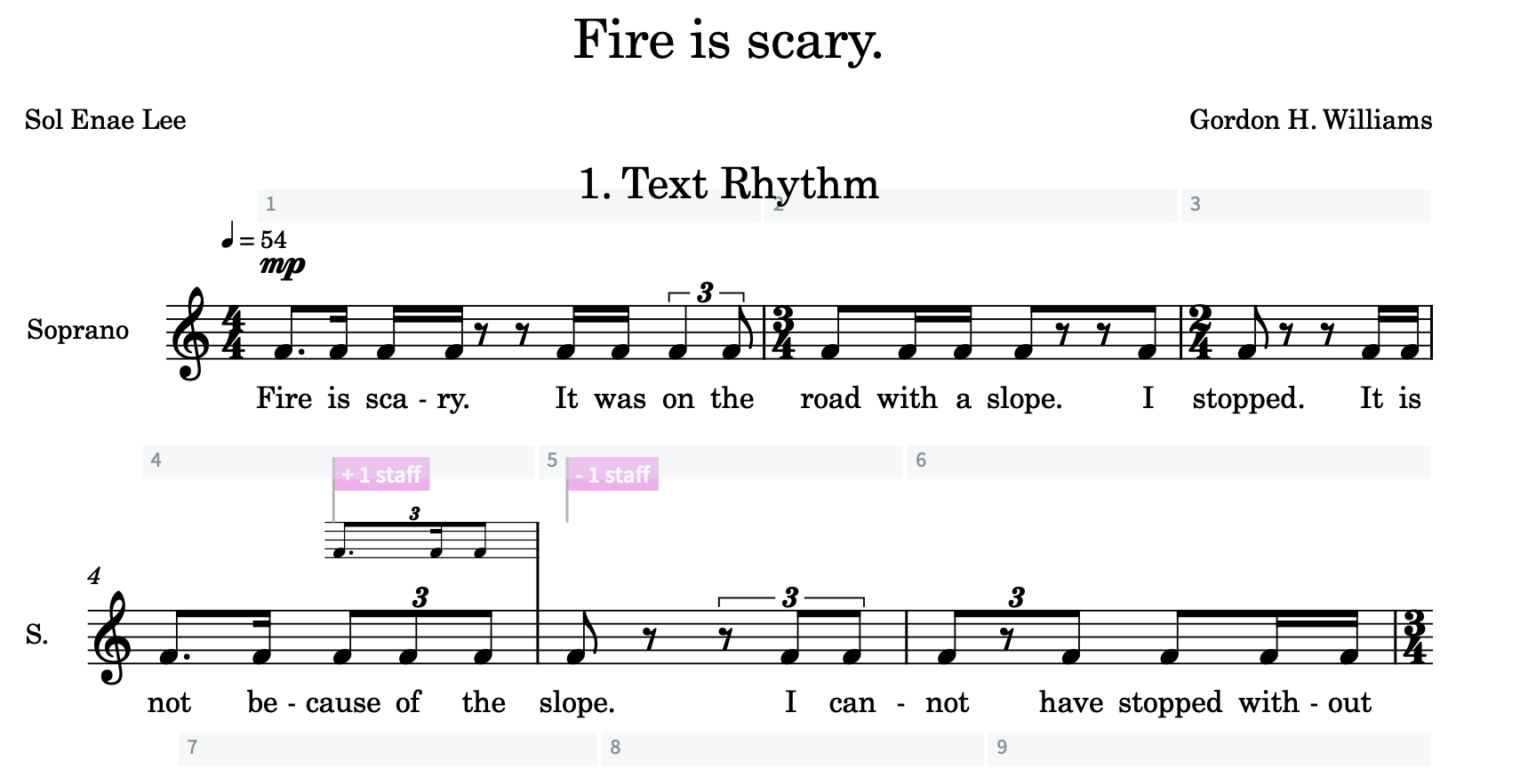

Translation begins with a deep study of the source material. I read over Sol’s text, spoke with Sol about the inspiration and process for making the text, and even had my partner record herself speaking the text, so that I could listen to it spoken back. I began moving the text into music by notating the rhythms of the speech and finding rhythmic ideas that would shape the musical language. From the first phrase of the text, ‘fire is scary’, came the melodic and harmonic material that would inform the atmosphere and world that the music would exist in.

Fig. 1 Notebook Sketch

As I worked to write each instrumental part, the idea of layering different flows of time became more and more important. The final line of the text of this movement, ‘I was not too shabby but I was worried about going back in time’, seemed to demand this. The different percussion parts took the rhythms that were gathered in the process of notating the speech, and began to move faster and slower against each other— creating a shifting, flowing music, that never stands stable for long.

Fig. 2 Text Rhythm (notation)