WHEN YOU SAY NOTHING AT ALL [listening as care]

Themes: Care, Self-organising, Collectivity

Methods: Artistic Practice, Conversation, Play

THERE IS NO SUCH THING AS

Once observed, silence is not actually silent. This is what I would contemplate after spending eight days in complete silence at a Vipassana meditation retreat.

Typically, silence is understood as an absence of sound, perceived as negative space, a dead time between sonic events. The fracture between the end of a song and the start of another, the pause of a finally empty street at night. Yet, as sound is a vibration of matter, absolute silence can only exist in a vacuum. This means that, given the ability to hear, there’s always some sound idling within silence.

François J. Bonnet1 writes that: “there exists a threshold of noise beyond which there is silence,2” meaning that silence is made of sounds that do not draw attention to themselves. What does or does not captivate one’s attention might be a matter of contrast. In fact, silence often coincides with ambient noise, or background noise, which—like absolute silence if it could be experienced—has the quality of invariability. While I sat there meditating, it was the persistence of cicadas that made their crepitation fall into the backdrop of hearing, revealing their presence only when they stopped crackling suddenly, with perfect synchronicity.

Inspired by Zen practices, John Cage, an American artist, and music theorist, made substantial use of silence in his pieces, precisely with the intention of drawing attention to what happens acoustically outside of what was then considered music. To him, silence is composed of any sound that is not intentionally made.3 Even his eccentric lectures often consisted of silences of different durations, as they open “the doors of the music to the sounds that happen to be in the environment.4”

The same way the silence of meditation can favour listening to converge towards neglected sounds, silence can hold space for careful listening that goes beyond the sensorial perception of sound, aiming at the meanings and implications that sounds carry. Silence can allow for the attention to shift to what usually is under the threshold, hidden behind the cacophony of everyday life.

Indeed, silence is not merely sonic material, but also a social, embodied experience that assumes multiple meanings.

SILENCE AND AGENCY

The significance of silence is rooted in culture, history, power dynamics and specific circumstances. Sure enough, my own attitude toward silence comes from the fact that I am a daughter of the West: Euro-American thought promotes voice and speech as important forms of agency, defining the speaking subject as able to exercise her democratic power. Western thought, from Plato to Saussure, designates spoken language as the primary human medium for addressing reality. Besides, in my late teenage years I actively pushed myself to speak more often to disrupt the passive and acquiescent role of women in society. I spurn the stillness, on the one side afraid to hear the crickets of something left unsaid, and on the other convinced that to be acknowledged and find my place in the world, I must speak. At the intersection of one’s position and relative power within a social group is where silence becomes a political matter. Who gets to speak and who doesn’t? Does my silence always correspond to a form of impotence?

Speech and agency are unquestionably linked, and history has often shown the problematic material and symbolic erasure of voices and people: from the censorship imposed on dissident groups by totalitarian regimes, to the negated access of people to positions of power based on gender, race, ability, and nationality. Nonetheless, the ability to speak isn’t the only channel through which to affirm agency. On the one hand, those who can’t speak might be doing so as a strategic choice of self-protection or resistance; on the other hand, I believe one should be able to enjoy one’s rights even when unable to speak.

In other words, silence is relational: it is not solid immutable matter, rather, its meaning is flexible and emerges from the social context it appears in, affecting in turn the dynamics it originated from. Silence becomes weighty when it is an expression of power imbalance: it exposes how structural inequalities present on a wider societal scale can be reflected in interpersonal behaviours within the personal sphere. Silence is also a verb.

[In this regard Eduard Glissant’s notion of “opacity” comes to mind. The philosopher distinguishes “the right to difference,” because it can bring to a reduction of the complex identity of the colonised in order to make it transparent and understandable to the coloniser, and as such assimilated by the latter. Glissant demands instead for “the right to opacity:'' instead of trying to grasp the Other and to undestand the Other through one’s own systems, Glissant proposes to accept someone else’s opacity, accept their unknowns. Opacities can coexist and converge, weaving fabrics. To understand these truly one must focus on the texture of the weave and not on the nature of its components. For the time being, perhaps, give up this void obsession with discovering what lies at the bottom of natures. Édouard Glissant. Poetics of Relation, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 190.]

The verb to silence suggests an action of restraining or dimming an acoustic or verbal event and can be intended as an oppressive act. Taken as such, the act of silencing, whether deliberately or unknowingly, is to negate someone or something of agency and visibility, making them less noticeable. Those who lay outside the dominant norm are taken less seriously. In her book White Innocence: Paradoxes of colonialism and race, Gloria Wekker6 shows how it is culturally embedded that often white people feel more entitled to speak than others in the public arena. Similarly, back in 1991, scholar bell hooks7 wrote of the exclusion of black feminists from academic discourse. The explanation offered was that their work was “not theoretical enough.”8

In this sense, I came to view silence not only as a verb but also as a space of friction that puts two or more people in relation to one another. Just as Cage’s pieces were dependent on the silencing of the performer and their audience.109 Despite their apparent immateriality, all sounds and voices take up space and are an attempt to be heard, usually at the cost of other sonic events. Sound has power and the ways different voices interact follow a variety of scripts, causing friction at contact.

INVISIBLE SCRIPTS

“Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion.” Scholar Jo Freeman11 has analysed these dynamics within proclaimed horizontal and leaderless groups, where she observed how informal elites form because of a lack of explicit structure12. The resulting exchange of information produces a lack of accountability, because “as long as the structure of the group is informal, the rules of how decisions are made are known only to a few, and awareness of power is limited to those who know the rules.”13

This is reflected in the conversational dynamics of a group, as every type of verbal exchange has an inherent protocol, concerning its content, aim, rhythm and the roles of its participants. While it’s obvious that call centres communications follow specific scripted patterns, and it is accepted that there are unambiguous procedures of interaction in a courtroom, at a parliamentary debate and within other formal institutions, other patterns fail to be recognised. Again and again seemingly informal exchanges also assume, maintain and reiterate a form. I could see this happen among my peers during my studies: one of the usual outspoken and more extroverted students would often take the stage. After a few months of being in class together, inadvertently assumptions had been built around who would for sure have something to say, without leaving much room for hesitation and reflection before jumping into the conversation.

The scripts of conversation pertaining to different contexts are often implicit, invisible, yet everyone has learned and embodied them. This is because protocols, too, are informed by cultural, racial, historical, and power settings. They are produced by and reproduce them.

Artists Antonas and Thanos Zartaloudis argue that even if a protocol consists of a closed set of replicable rules, it is admittedly understood as fabricated and therefore ductile: it can be challenged and modified. Every action in life is scripted in a protocol and being aware of the protocol makes it possible to perceive the script as an empty recipient of new and different performances.14

Indeed, intentionally bending protocols of conversation can interfere with the existing social dynamics within a specific group. Each participant can train their ability to hold silence, listen to the other carefully, and notice their capacity for doing so or lack thereof.

This is not to say that spontaneous dialogues must be avoided at all costs, nor that protocols can always ensure a fair and qualitatively desirable outcome of every conversation, as excessive use of them might result in a very rigid and formal exchange, where there’s no space for serendipity, unplanned tangents and jokes. Interruptions and overlaps are not inherently bad, as they can favour words and gestures of empathy.

LISTENING WITH

Recently, feminist thinkers have been offering new perspectives on silence by shedding light on the potentialities that lie within it, rather than its oppressive functionality.

Indeed, for a person to be silent is to inevitably create the possibility for another to speak and at the same time, to be silent is the precondition for listening. Caroline Godart15 writes on the concept of the interval developed by Irigaray,16 describing how silence can generate a form of listening through which two individuals can approach and welcome each other with their mutual otherness: “in order to truly listen, we must act from a position of complete openness and renounce our own mode of approach to the world in order to let the others unfold.”17 In the context of rhetorical studies, but still reflecting on silence as a method for transformative change, Ann Russo18 describes silence as a way to overcome the entitlement of white feminists, who benefit from structural advantages compared to black feminists: she proposes the tactic of “listening up” in place of “speaking up” as a way to foster true allyship. By learning to support peripheral tasks and restraining from determining the direction of the conversation, Russo envisions how embodied silence can pave the way to active listening, a practice of accountability to the work of transforming, rather than reproducing, deeply entrenched power relations. 19Silence is maybe not a sufficient condition for active listening, yet it is the space in which this learning takes place. Silence is where the friction happens, where two or more subjects encounter one another and recognise each other’s differences. Giving into this friction can bring about a listening with: not a mere listening to the other, but with the other. Listening-with is a pursuit of a high degree of attention and involvement with the other, with the intention to go beyond one’s own preconception of what the other might need or be, thus allowing the other to transform oneself.

This translates into practice through the learning process of allowing one’s ideals to be withheld momentarily, to unfold spaces of understanding and well-being across personal differences.

In short, listening-with is a form of care, a listening in relation. This shift from the individual sphere to the shared sphere is a fundamental aspect of care that is often forgotten in contemporary Western notions of self-care, where it has become the responsibility of the individual, who is thought to be able to buy care and to have all needs met. Care is instead a form of labour that materialises in interdependence. To give care one needs someone who accepts the care, to speak meaningfully one needs someone that listens.

Silence, listening and care alike are relational practices grounded in mutuality that can help move towards more generous and equitable conceptions of caregiving and create acceptance for care receiving.

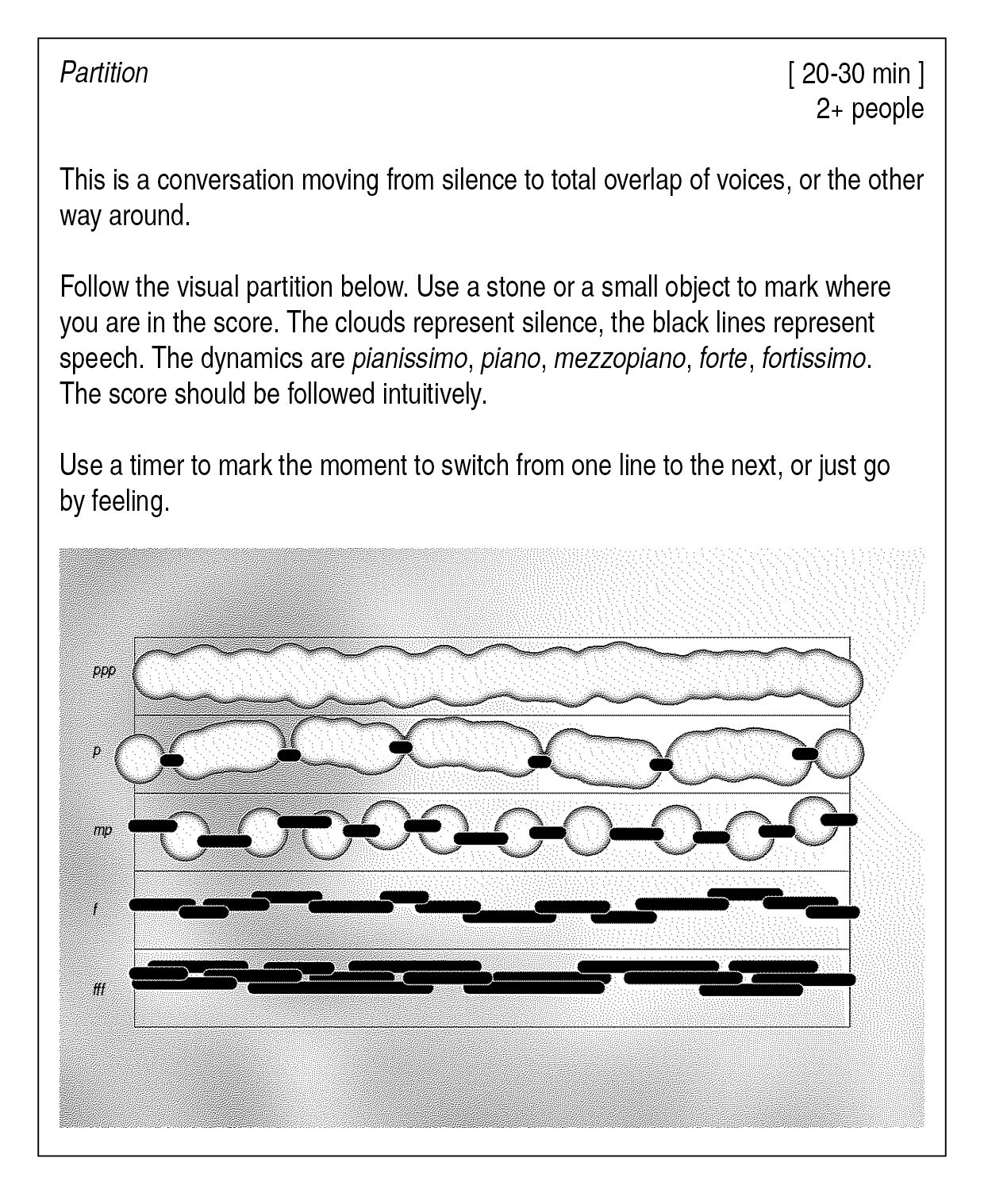

GATHERING SILENCE

Circling back to the understanding of protocols as ductile containers, and how they are produced inter-subjectively, they can function as counter-hegemonic practices. A practice of silence can facilitate a shift in personal behaviours that can hopefully ferment a culture of mutual care and listening-with. Furthermore, enacting listening-with protocols can result in a collective and entangled understanding of society, rather than one composed of separated individuals. Starting from the small scale, breaking, and reassembling protocols can take many forms and be applied in situations of conflict, within communities, institutions, classrooms, and workplaces.

Protocols for listening-with are an attempt to promote relational and collaborative approaches in place of competitive ones, not as an all-encompassing solution, but as a step towards carving out these very necessary basins of silence and propagate a practice of being open and accountable to each other.

How has working with silence influenced your go-to modes of communication, and ways of working collectively with others?

I’ve started being more aware of my habit of formulating conclusions too early and completing other’s sentences: when I pose a question to a group now, I tend to leave more time for elaboration and answer, holding a bit of silence before I intervene, to welcome seemingly tangential responses. In addition, having the knowledge of these modes and tools for conversation, I am less shy about employing them and I am eager to try out new methods and proposals from others when the opportunity arises.

I think that the process of working with silence and School of Commons has also taught me to accept that in the process of developing a project, be it alone or collectively, it’s okay to go through a phase where you feel you have little control and understanding over what you are doing. That the collective mess in between can be a slow but fertile ground. The same way silence can teach to sit with the not-knowing for a moment.

François J. Bonnet is a composer, recording artist and theoretician. He is Director of Groupe de Recherches Musicales of the National Audiovisual Institute in Paris.

François J. Bonnet, The Order of Sounds: A Sonorous Archipelago (Falmouth: Urbanomics, 2016), 54.

Douglas Kahn, "John Cage: Silence and Silencing." The Musical Quarterly 81, no. 4 (1997): 558.

John Cage, Kyle Gann. Silence: Lectures and Writings, (Wesleyan, 2011), 10.

For more on the topic of silence and sexual harassment, see: Cheryl Glenn, "Silence: A Rhetorical Art for Resisting Discipline(s)." JAC 22, no. 2 (2002): 261-91. Accessed October 26, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20866487

Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of colonialism and race (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017), 168-173. Gloria Wekker is an Afro-Surinamese Dutch scholar, whose extensive body of work has brought questions of colonialism, race, gender, sexuality and diaspora to the forefront of critical scholarship on the Netherlands and the Dutch Empire.

bell hooks is an African American feminist activist, professor, and writer. Her books look at the function of race and gender in popular culture, education, art, history, and sexuality.

bell hooks’ approach is one that strives at uniting theory and practice. To her, theory should help individuals integrate feminist thinking in everyday life, hence she writes often from personal experience, “from the concrete,” choosing a writing style that speaks to the widest audience possible. This clashes with the usual assumption that scholarly writing should be objective, impersonal and should use very formal language. “Theory as Liberatory Practice,” Yale Journal of Law & Feminism (1991), 4.

Kahn, "John Cage: Silence and Silencing," 560.

Kahn, "John Cage: Silence and Silencing," 560.

Jo Freeman, “The Tyranny of Stucturelessness,” a text that was first published in 1972. https://www.jofreeman.com/joreen/tyranny.htm Jo Freeman is an American feminist, political scientist, writer and attorney. She has been active in organizations working for civil liberties and civil rights movements.

Elites are nothing more, and nothing less, than groups of friends who also happen to participate in the same political activities.” Jo Freeman, “The Tyranny of Stucturelessness.”

ibid.

Aristide Antonas and Thanos Zartaloudis, “Protocols for a Life of the Ordinary,” e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/positions/204038/protocols-for-a-life-of-the-ordinary/ (Accessed: 3 November 2020).

Caroline Godart is an editor, dramaturge, scholar and educator based in Bruxelles. She studied philosophy, feminist and queer thought, cinema and literature at Rutgers University in New York.

Luce Irigaray is a Belgian-born French feminist, philosopher, linguist, psycholinguist, psychoanalyst and cultural theorist who examined the uses and misuses of language in relation to women.

Caroline Godart, "Silence and Sexual Difference: Reading Silence in Luce Irigaray." DiGeSt. Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies, no. 2 (2016), 16.

Ann Russo is the Director of the Women's Center and a Professor in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies. Her scholarship, teaching, and organizing focus on queer, antiracist, and feminist movement building to end violence and to build socially just and caring communities. Integral to her work is exploring the praxis of building alliances and coalitions for social change.

Ann Russo, “Feminist Accountability: Disrupting Violence and Transforming Power,” in Silence, Feminism, Power Reflections at the Edges of Sound, ed. Sheena Malhotra and Aimee Carrillo Rowe (Palgrave Macmillan: Northridge, 2013), 34-48.

Eleonora Toniolo

Eleonora is a designer, currently pursuing her Masters in Social Design at DAE, Eindhoven.

Thanks to Yanna, Deepak, Jan, Jerlyn, Nicolae, Charlotte, Joanna, who participated in the [ arranging conversations ] workshop and came up with the Double Role and Rotating Role protocol. Many thanks to Jonathan for the ongoing thoughts exchange on all matters of conversation and silence, and for contributing significantly to the protocols and their translation into practice.

Download: download the protocols

pdfRead & Repair feat. Minimum Viable Learning

13.12.2020, 13.12.20, 11:00 – 13:00

Come and make yourself comfortable, read together with others. Each session of Read & Repair is looking at a different text, sometimes guided by a guest. Our last editions have been taking place online, and so does this one. Find out more