Conspiratorial Signs describes the background and practice of serial protester and conspiracy theorist Frank Chu. A staple of the early 2000s San Francisco community and local media, Frank’s protest practice and celebrity status foreshadowed much of the information and political economy today. Conspiratorial Signs considers the ethics and strategies of conspiracy theories, including – how they are racialized and exploit those in vulnerable situations, as well as their potential for organizing and affecting change through World-Building, Hyperstition, and Fictioning.

Conspiratorial Signs

At the beginning of the Frank Chu archive I had a straightforward idea: my goal was to contact conspiracy theorist and serial protestor Frank Chu—an eccentric figure and staple of my childhood growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area—interview him, and make reproductions of as many of his signs as possible from his more than 25 years long protesting career. However, the more I reflected on the prompt and researched about Chu, the less clear this became as an objective.

Entering School of Commons in 2023 I was intrigued by the power of conspiracy theories. I originally conceived of my proposal during COVID-19 lockdowns, when QANON conspiracies and COVID denialism were at a fevered pitch. I was struck by the absurdity of these movements, but also acknowledged their appeal. Rather than accepting a tenuous and ambiguous reality where paranoia and uncertainty dominated, these conspiracies allowed their believers to become participants in narratives that offered explanations and a promise of closure.

At the same time, a surge in anti-Asian racism took shape, shaking the Bay Area community where I grew up and people of east Asian descent all across the US and Europe. While it’s been accepted that the rise in anti-Asian sentiment was caused by increased anti-Asian rhetoric, it’s still difficult to fully understand the cause and effect. A depressing and familiar pattern took shape, in which either unruly teenagers or the mentally disturbed unhoused would attack elderly asian people. Sometimes, the result of a robbery escalated unnecessarily. At other times the attacks seemed seemingly unprovoked and at random. I began to worry about my mom, who has lived alone since my brother and I moved out about 20 years ago. She is active and engaged with the community around her, and suddenly her independence was a cause for concern, as going shopping for groceries, waiting in your car at an intersection for the light to change, and taking the subway acquired a new level of risk. This fear was accentuated when a family friend’s father was killed while taking his morning walk in a mugging.

While grappling with these sad realities, my mind drifted and fixated on Chu— as an Asian-American protester and conspiracy theorist he seemed to embody that moment in several strange ways. I remembered Chu from my youth in the mid 2000s, around when he gained increased attention as a local oddity—I presume from his presence at anti-war protests and the rise of web 2.0 and the blogosphere. Chu began demonstrating in 1999, constructing a unique language to describe his conspiracy theory. This language was expressed both in words and graphics—with Chu communicating largely through protest signs that had a compelling graphic discipline—using a black background with type set in all capital letters in the Impact typeface, with rows of words alternating between white, red, blue, green, and purple type. A few years before I had become interested in Chu because of his unique visual language, and was now inspired to revisit him hoping to grasp insight into the role of graphics in conspiracy theories, the ethics of platforming someone like Chu, and the racialization of conspiracy theories.

![[photo of Frank Chu protesting c.1999]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/4e365ce9b57b03e304a8cadea108bcb288e56885-524x378.png)

photo of Frank Chu protesting c.1999

Frank Chu has been protesting almost daily since the late 1990s, sharing his conspiracy theory that he is an unwilling actor in an intergalactic television show called “The Richest Family.” He claims the show, coordinated by aliens from the “12 Galaxies,” is filmed using "telepathic inventions" and hidden surveillance cameras that "disappear into thin air1". According to Chu, the show has achieved immense intergalactic popularity and financial success, but he has not been compensated. He believes he is owed billions of dollars and accuses U.S. intelligence agencies and politicians of collaborating with the intergalactic media—including Universal Studios‚ – to deny him payment. Chu’s goal is that he’ll gain enough popular support to get an audience and appeal his situation to the United Nations, who will take action against the 12 Galaxies. In an almost uncanny way, Frank Chu’s protests share much in common with more popular and accessible conspiracy theories. They center him as the protagonist rather than a subject, and challenge an oppressive cabal to get what he is owed.

∞

In their book “Speculative Communities: Living with Uncertainty in a Financial World” Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou observes a social trend towards mysticism. He argues that we’re overwhelmed with data on a daily basis, yet this data is largely inscrutable, leaving us with the feeling that we have all the information we need to understand the world around us, but no ability to decipher it. As a result we end up looking for explanations anywhere we can find them. During the COVID-19 pandemic this feeling was particularly salient and relatable, as there was so little certainty in how we would make our way through such a predicament. Instead we would watch case numbers, fatalities, and recovery rates rise and fall as we waited for some, yet unknown, resolution to take shape.

Yet, despite these uncertainties, we’re experiencing the effects of harsh and difficult to understand realities everyday— often being told that what is plainly happening in front of us, is in fact incorrect. Be it the media selling us on the health of a failing economy, politicians villanizing civilians and children to enable a genocide, or opportunistic hucksters promising revolutions in work via Artificial Intelligence. In the same way divination provides explanation and a course of action in our daily lives, so too can conspiracy theories. In particular, online platforms allow for the participation, development, and dissemination of conspiracy theories which reframe us as agents within our stories, rather than victims. Not only can we react to and share information before it can be validated by experts, we’re also capable of re-defining information to fit our own narratives through collective storytelling. This practice can be compared to the act of Hyperstition—the idea that creating and disseminating ideas and stories can bring them into reality.

AI generated imagery widely shared and cited on social media3, if taken in good faith interpreted as being real, depicting fictitious events during Hurricane Helene – a natural disaster embroiled in conspiracy theories about the government controlling weather4

AI generated imagery widely shared and cited on social media5, if taken in good faith interpreted as being real, depicting fictitious events during Hurricane Helene – a natural disaster embroiled in conspiracy theories about the government controlling weather6

While many conspiracy theories today follow these rules, the most notorious example in recent history was Qanon—a conspiracy theory which has constructed a complex mythology about the “Deep State” and believed Donald Trump would overthrow the US government in a violent reckoning. While QAnon as a movement fizzled after the failed January 6th coup, and “Q Drops” —– messages posted online by the movement's mysterious leader—ended in 2020, the conspiracy theory still holds valuable lessons to reflect upon. In their article Blank Space QAnon. On the Success of a Conspiracy Fantasy as a Collective Text Interpretation Game by Florian Cramer and Wu Ming 1, they posit that QAnon functioned similarly to an Alternate Reality Game (ARG). Describing the attributes of ARGs they state: “They [ARGs] contain puzzles and mysteries that players solve by finding information outside the game and sharing it with other players. Alternate Reality Games often have open ends. As their name suggests, their game plots construct alternative realities that overlay the players’ everyday life and, so-to-speak, charge it with magic.” Cramer and Ming 1 argue that QAnon possessed many of these same features, allowing participants the opportunity to participate as players in a magically charged reality.

Although QAnon has largely dissipated as a movement, many of its members and ideas have taken hold in mainstream politics. With conspiracy theorists serving in Congress, and ideas first proposed in conspiracy theories becoming part of major party platforms.

∞

Part of what made Chu’s story so intriguing was a question of intent, agency, and authority. It’s difficult to pinpoint when the root took hold that would lead to Frank Chu’s protest practice, but it seems to have begun in his early life. According to his own accounts, Chu attended UC Berkeley, but claims discrimination from the 12 Galaxies—the extraterrestrial force plotting against him—forced him out of the school7. It’s been reported that in 1985, when he was 24 years old, he took eleven of his family members hostage in Oakland Chinatown—beating them and shooting at a police officer through the door who was called to the scene to intervene8. Chu claimed the shooting was in self-defense, but was still sentenced to nine months in jail. Popular belief is that Chu began protesting in his late twenties in 1998 or 1999, although some accounts mention him protesting earlier in the 1990s.

Popular perception, and from what I can gather are first-hand but unprofessional diagnosis, identifies Chu as schizophrenic, although Chu denies this diagnosis9 (searching online I found a LA Police Department training document that uses an interview with Chu as an example of schizophrenia10). While these accounts are in no way definitive, I think it can be safely said that Chu faces personal challenges that prevent him from living a normal life. Despite, or perhaps due to, this condition, Frank Chu was embraced by local media in a way that is both celebratory and uncomfortable.

![[Front and back views of Frank Chu’s sign at 2011 SantaCon showing the Laughing Squid advertising on the back of Chu’s sign]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/780b071b6affea9aa01550c9e70b0bb735b8b28b-1156x754.png)

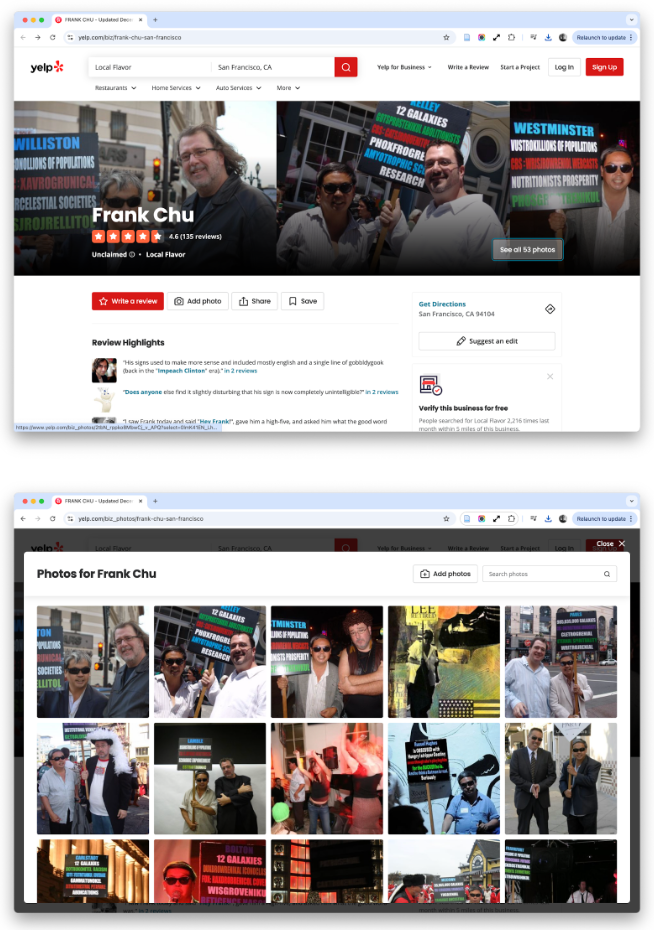

One of the most troubling aspects of Chu's celebrity was how local companies used Chu for advertising and sponsorships. In a gesture that was both charitable and self-promotional, local advertisers paid Chu to attach their advertisements to the back of his protest signs, a complex act somewhere between support and exploitation. According to Frank Chu’s Yelp page (creating a business yelp page for a mentally unstable individual seems in poor taste to say the least), at one time Frank received sponsorship from at least 10 businesses and individuals, including at least two local politicians13. On the one hand, these transactions indicate a legitimate care and admiration for Chu, yet at the same time they feel demeaning and exploitative. On the Frank Chu business page, Yelp user John S. sums up the situation well:

Screenshots of Frank Chu’s yelp page

Screenshots of Frank Chu’s yelp page

Chu has also had a relationship with artists, documentary filmmakers, and curators. In their essay MERIWETHER / UTROPRULLIONS OF POPULATIONS / ABC: PRETROGRELLITOL ROBOTICS/ GESTATIONAL PREVALENCE / OTROWRELLIGUL author Chris Fitzpatrick recounts their trip with Frank Chu to the 9th Shanghai Biennial where The Richest Family; The Early Episodes a video project by Floris Schönfeld made with Chu as the subject was being exhibited. Fitzpatrick provides biographical information about Frank, interspliced with transcription of a psychotic episode Frank had while on the trip. The work is touching in its sympathy for Frank, and also implicitly questions the reception of his project and those who platform him, including the author.

∞

Graphic symbols have played a crucial role in the spread of conspiracy theories. On one hand being presented as "evidence" to support these narratives, and on the other being used as rallying points for organizing. Since the popularization of Web 2.0, which allowed individuals to publish online, we’ve seen an accelerated use of images, graphics, and symbols in conspiracy theories (this era of self-publishing also led to the popularization of Frank Chu as a minor celebrity). As “users” gained access to distribution channels and design tools, graphic evidence became a component of amateur investigation and discourse. Most national tragedies have become fodder for conspiracy and use graphics as evidence to support their claims – from perceived discrepancies in the crash sites of the 9/11 terrorist attacks highlighted in photos of rubble, to accusations of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting using “crisis actors” to create a false flag operation proven with photoshopped comparisons from the crime scene and of news clips, to microscopic “proof” of “5G nanochips” in the COVID vaccine16.

![[Analysis of Comet Ping Pong Signage by Pizzagate conspiracy theorists]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/2e618c37adcafd3138b7c79694ebc4d151503af4-928x812.png)

Analysis of Comet Ping Pong Signage by Pizzagate conspiracy theorists

While these conspiracy theories are themselves not necessarily part of a larger unified theory. Conspiracy theories like Pizzagate and QAnon relied heavily on symbolic interpretation—with even simple shapes, like triangles, being seen as clues. These symbols lended visual legitimacy to otherwise baseless claims, while allowing participants an access point to build on conspiracies and make linkages in unexpected places.

![[Various Q logos]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/0b0d7e4cf1a5fcd1de2e5e9a1ea3d650d99bed76-1092x222.png)

Various Q logos

Furthermore, through use of corporate branding methods—for instance the mutability of the “Q” logo—followers could create their own variations of the Q logo to fit their personal identities and adapt to different protest situations. These frameworks also encourage the appropriation of existing forms to further their conspiracy theories—such as the use of emoji to evoke the phrase “follow the white rabbit”—a code used by QAnon followers to communicate something as a point of interest to fellow conspiracy devotees.

![[Luigi Mangione’s (@pepmangione) x.com profile banner featuring the Pokémon Breloom]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/4705b66d4e42de397bbeaf077e2e55496a38e359-1304x432.png)

Luigi Mangione’s (@pepmangione) x.com profile banner featuring the Pokémon Breloom

Recently the alleged assisination of UnitedHealth CEO Brian Thompson by Luigi Mangione has led to conspiracies both about Mangione’s guilt as well as his motivations. An example of graphic symbolism that has become a site of popular imagination was found in the banner of Mangione’s x.com profile page. David Gilbert for Wired magazine writes: “In his profile on X, Mangione features the Pokémon Breloom, which is the 286th Pokémon. Mangione also had posted exactly 286 times on X when he was arrested. 286 is also the code health insurance companies use “when the appeal time limits for a health care claim are not met.” Other users on TikTok pointed out a potential link to the Bible, with Proverbs 28:6 stating: “Better is a poor man who walks in his integrity than a rich man who is crooked in his ways.”“

While unclear what Mangione meant through the use of the Breloom character – it has also been posited that Breloom’s mushroom like appearance is based on Mangione’s interests in psychedelics – the phenomena is a demonstration of how these symbols can quickly become components in world-building.

∞

Chu also employs graphics and language to build his world, as well as make his conspiracy accessible and grow its popularity. While Chu’s conspiracy is largely impenetrable, he has been able to describe the complex set of circumstances and actors that compose it effectively via protest signs using small phrases that list political figures and celebrities, media organizations, government agencies, science-fiction entities, large numbers, and his own constructed language modifiers. Chu’s signs visually and linguistically follow a recurring pattern. Where each sign displays 5-6 lines of short text, each of which indict a different component of the conspiracy, always beginning with a key figure, and each subsequent line describing some complicit party or attribute of the 12 Galaxies.

Examples of Frank Chu’s sign pattern

Chu’s continued protests have made him into a local celebrity, drawing the attention of media and artists to raise his profile to international heights (at least to a small audience). While it’s debatable why Chu was able to capture attention and imagination, surely his unique graphic and lexical language was a part of this. Chu’s invention of words related to galaxies, actors, and large numbers help to create the universe his theories inhabit. Although he communicates his ideas in video and audio interviews and speeches, the most salient form his constructed language takes shape are in his protest signs.

During the Seoul-based 2024 protests calling for President Yoon Suk Yeol's resignation, lightsticks for K-Pop groups became an organizing symbol (graphic by Jiwon Park)

In organized action protest signs can create a visual archive of a moment, mood, and movement. However, while these signs collectively represent movements, they typically lack a cohesive visual aesthetic. Chu’s signs in contrast echo a traditional graphic design and branding approach to defining a visual language. However, compared to a more professionalized and intellectual approach to design – which typically centers minimal and modern design ideals – Chu’s visual language feels more akin to the vernacular graphic language of protest and small scale advertising.

Precedents and contemporaries for Chu’s sign-language can be found in the work of designer-printers Colby Printers from Los Angeles California19—who since their inception in the mid-twentieth Century helped define the LA cityscape through their signs which employed bold, all-caps type, set on vibrant neon and fluorescent colored-background, often using “split-fountain” gradients. Or a much darker parallel can be drawn to the signs of the Westboro Baptist Church, which employ a similar graphic and typographic style infused with hateful and headline grabbing slogans20. In both cases the sign’s visual design language is both fixed and flexible. Creating iconic visuals from text and colors for “brand recognition”.

While conspiracy theories often exist in an amateurish, memetic space, Chu's are no different. Chu’s graphic language distinguishes itself with its consistency and discipline, achieving something many professional graphic designers are unable to replicate.

∞

Conspiracy theories are often racialized, and can be used to discriminate against outsiders by redirecting legitimate outrage to undeserving targets. An example of this phenomena, and one of the most despicable narratives of the 2024 presidential election has been the demonization of immigrants, much of which has taken shape via conspiracy theories. A low point in this narrative came about during the Harris vs. Trump Presidential Debate on September 10, 2024, when president Trump promoted the false claim that Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio were eating residents' family pets. “In Springfield, they’re eating the dogs, the people that came in, they’re eating the cats… They’re eating the pets of the people that live there.” Trump said when asked about his opposition to an immigration bill that aimed to increase border security. The theory can be traced to a post on a private Facebook group where an individual recounts a story they heard second hand where a missing cat was found being butchered by their Haitian neighbors.21 The theory continued to gain traction online, falsely claiming immigrant residents were slaughtering and eating ducks from a local park. These claims were then bolstered by a random assortment of videos which could be interpreted to fit the conspiracy, but were hoaxes, or otherwise misattributed.

This moment highlights a new mainstreaming in conspiracy theories in US politics. Where the specific narrative is admitted to be fictitious, but claims to point to a larger truth. After the theory had been widely debunked, incoming Vice President JD Vance said the following in an interview on September 15, 2024: “The American media totally ignored this stuff until Donald Trump and I started talking about cat memes… If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that's what I'm going to do."

∞

Frank Chu was born in 1961 in California, and grew up in Oakland Chinatown. The San Francisco Bay Area has a sizable and influential Asian American population, as it was home to the first Chinese immigrants to the United States in the late 19th century. Since then it has been a locus for the definition of Asian American identity – being both the home to the modern concept of “Chinatown”s from an architectural aspect, as well as the inception point for the term Asian American which was established during the student protests of the 1960s at University of California Berkeley and San Francisco State University which led to the establishment of the first Ethnic Studies programs.

The COVID-19 moment, while a global tragedy that impacted essential workers and the economically depressed disproportionately, had a unique effect on the East Asian diaspora. Due to the virus’ origin in Wuhan, China, people of East Asian descent became the target of hate crimes, discrimination and casual racism as well as the popularization of conspiracy theories that the virus was engineered by the Chinese government towards nefarious ends.

As with other conspiracy theories, graphics also became a tactic to further anti-Asian sentiment, becoming the latest example of such practice rooted in the San Francisco Bay Area as the first site of East Asian immigration to the United States. During COVID-19, one notable example of anti-Asian racism that was made famous, was shared by Lululemon’s senior global art director as a “joke”. In his post, Trevor Fleming shared a mockup of a coronavirus-themed t-shirt showcasing "Bat Fried Rice", chopsticks and a Chinese takeout box using a “wonton” style font. These graphics were reminiscent of political cartoons that appeared in San Francisco newspapers in the early 1900s, and were some of the first anti-asian propaganda made in response to the arrival of the first wave of mass migration from East Asia to the US. These comics were part of a larger effort to depict Asian immigrants as being unclean and dishonest – comparing them to insects and animals, and using crude penmanship to evoke “Chinese-ness”. Undergirding this effort to demonize Chinese immigrants was an effort to paint Chinese immigrants as foreign agents acting on behalf of the Chinese government to undermine the American worker.

∞

While these examples of anti-Asian racism have had a tangible effect on individuals’ safety, their effects were for the most part psychological. Yet, like the activities of COINTELPRO in the 20th century—who destabilized radical movements by people of color via the manufacturing and propagation of conspiracy theories. The US government continues to use conspiracy to undermine and destabilize communities abroad during the COVID-19 pandemic in response to sinophobia. Earlier this year it was revealed that the US Government spread anti-vaccine conspiracy theories in the Philippines and throughout Southeast and Central Asia during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result of the US COVID-relief effort, in which the US government monopolized international resources and caused worldwide shortage in PPE and vaccines, poorer nations without robust health infrastructures—often US allies—were left with few options in their own anti-Covid campaigns. Given the circumstances these nations embraced China’s anti-Covid effort, which, in addition to extreme measures within their own country, involved distributing masks and other PPE resources, including the China-developed Sinovac Covid vaccine, around the world.

Sensing a potential turn in public opinion, with growing pro-Chinese sentiment due to their global Covid relief efforts, US Military officials initiated anti-Covid– – and in their view anti-Chinese—propaganda methods across social media in South East and Central Asia. These efforts involved the creation of fake social media accounts to spread vaccine disinformation.

Reporting from Reuters found over two-hundred x.com accounts linked to the American psyop. Notably, all accounts were created in the summer of 2020 and used the slogan #Chinaangvirus (which translates from Tagalog to “China is the virus”). These accounts not only cast doubt on the effectiveness of face masks, and test kits, but also promoted conspiracies about the origins and compositions of the virus. Making a wide variety of accusations, ranging from claims that the vaccine itself was deadly, to stating that the vaccine contained pork in an attempt to dissuade Muslims from inoculation.

Although it’s difficult to assign a specific measure—a number of Covid cases, deaths from Covid, or a more generalized measure of suffering from the impacts of the virus, that resulted from the US’s anti-vaccine propaganda, it is clear that the Philippines was severely impacted by Covid-19. Speaking directly to the effects of the American anti-vaccine campaign, Dr. Nina Castillo-Carandang, a health expert in the region stated “...I’m sure that there are lots of people who died from Covid who did not need to die from Covid”.

Both were victims of conspiracies and/or called conspiratorial for calling them out. People of color, and Asian people worldwide, were again shown to be the victims of conspiracy theories.

∞

Now, at the end of my School of Commons cycle, I am reflecting on Chu and my relationship towards him. My initial motivation came about due to an earnest interest in his sign graphics. However, the more I learned about Chu, the more complex and challenging my understanding of him became. My participation in School of Commons centered on Chu and his public persona, which poses significant questions about mental health and exploitation—something many art projects that have centered Frank in the past have also coped with.

I’m also left to reflect on conspiracies more broadly, and their impact on popular culture. Although Frank Chu’s personal conspiracy seems surely fuelled by delusion, it echoes a larger idea of exploitation and discrimination that marginalized groups experience everyday. Conspiracy theories can occupy a grey area between fiction and reality. Both pointing to larger truths that are difficult to prove due to their complexity, as well as being used as cudgels to harm and undermine the vulnerable.

This interest in Chu and conspiracy theories was intertwined in the COVID-19 moment, when conspiracy became a tool for dissent. Although I didn’t agree with the goals of these movements, which were dangerous and discriminatory, there was something inspiring about how they galvanized action and created solidarity— – as a Graphic Designer myself, I especially appreciated their use of visual art and graphic design to do so. After all, world governments and NGOs have long used symbols, graphics, and documentation to validate their fictions.

I wondered how we may use some of these graphic tactics to further more positive agendas. While graphics may only be a small piece in a larger movement, I have found inspiration in discourse around Fictioning, Hyperstition, Worlding, and their overlap with Graphic Design. In his 2018 essay Chimeric Worlding: Graphic Design, Poetics, and Worldbuilding, Tiger Dingsun writes:

“Under the methodology of chimeric worlding, there is a call for epistemic disobedience, as the decolonial theorist Walter Mignolo calls it, for we all operate under symbolic systems of oppression. As graphic designers we have the ability to take those pervasive systems and strip them for parts, combining them with other, more marginalized knowledge.“

While the danger of conspiracy theories is clear, I feel their potential is still underexplored. Maybe we can take notes from figures like Frank Chu to create our own narratives that grant us agency rather than consigning ourselves to being passive actors.

Chong, H., Li, C., Armin, J., Brown, M., Spring Workshop., & Spring Workshop. (2015). Stationary 1. Mimi Brown, Spring Workshop.

https://web.archive.org/web/20180612171855/http://www.timeoutbeijing.com/features/Art/157605/Lawrence-Lek-It-isn%E2%80%99t-a-manifesto,-it%E2%80%99s-a-conspiracy-theory.html

https://www.reddit.com/r/sanfrancisco/comments/1xb5cj/comment/cf9rfzj/

https://sfist.com/2008/05/27/frank_chus_wiki/

https://www.reddit.com/r/sanfrancisco/comments/1xb5cj/comment/cf9rrzh/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web3x&utm_name=web3xcss&utm_term=1&utm_content=share_button

https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/LAPD%20Expanded%20Course%20Outline.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Chu#/media/File:Frank_Chu.jpg

https://www.flickr.com/photos/ari/4181167120/

https://www.yelp.com/biz_photos/frank-chu-san-francisco

https://www.yelp.com/biz/frank-chu-san-francisco?hrid=-j7a_tNM4aD_MFguDh-9OA&utm_campaign=www_review_share_popup&utm_medium=copy_link&utm_source=(direct)

https://x.com/pepmangione?lang=en

https://rumble.com/v26tsok-5g-nanochip-found-in-the-pfizer-covid-vaccine-under-200x-magnification-proo.html

https://www.typeroom.eu/colby-poster-printing-company-a-legacy-of-fluorescent-power-made-in-la

https://walkerart.org/magazine/westboro-baptist-church-typeface, https://www.kpbs.org/news/national/2011/03/02/a-peek-inside-the-westboro-baptist-church

https://x.com/charliekirk11/status/1832883283199471676

https://x.com/JudiciaryGOP/status/1833154509222129884

https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/13129/the-latest-edition-of-shoo-fly, the author became aware of these comics during Chris Lee’s talk at the 2023 International Design Culture Conference at Seoul National University titled “Typographic Design as Visual Historiography, Racial Formation, and World Making” https://idcc.snu.ac.kr/2023/#cl

https://www.reddit.com/r/sanfrancisco/comments/1fl2duj/frank_chu_was_on_polk_today/

Chris Hamamoto

Designer, developer, and educator from the San Francisco Bay Area, now living in Seoul and teaching at Seoul National University.

![[Symbols mentioned in Principia Discordia and The illuminatus! Trilogy]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/9274d9c805c28def7dabeab3c7ddf794c16a986e-1240x372.png)

![[AI generated imagery used to promote the conspiracy that Haitian immigrants to the US were eating pets]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/19d261c38393d32a3ef1bbf6eb4c551a73317b90-708x756.png)

![[Anti-Chinese Cartoons c.1870]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/1cd222667a5b5e95e88c2a5d4a5538e35251137e-850x1008.png)

![[A September 2024 photo of Frank Chu protesting uploaded to the r/sanfrancisco subReddit]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/eodip22e/production/bcb82eada44fed9d48e1e41d812927a77e8b533f-646x866.png)