The right to housing is not only a matter of social justice but also takes on new urgency in the face of the climate crisis, which exacerbates the pressing global housing crisis. This crisis is intricately linked to the environmental impact of housing and construction, including skyrocketing land prices, the financialization of the real estate market, migration patterns, and exploitation of resources. However, in this era of climate crises, we must question the sustainability of our construction practices, given that the construction industry is responsible for about 40 percent of total raw material consumption and generates a staggering 88 million tons of CO2 emissions annually in Germany alone. We will use Zurich as a case study, examining specific legal and political frameworks and involving various stakeholders through Mapping and Visualization Tools and open sharing formats.

House’ it going? – The housing crisis in Zurich

The housing crisis is one of the many interwoven crises that constitute the broader Polycrisis of our times. Together, these challenges create layers of systemic instability and inequity, visible in structural problems and the inability of policies to address growing inequalities. To embrace chaos - the theme of ISSUES 2024 - we first need to understand it. By dissecting the complexity behind these crises, we can develop tools and methods to engage communities, navigate uncertainty, and seek pathways toward meaningful change. Therefore we will share our input on the housing crisis, the situation in Zurich and on our way of working through the crisis. Here, our Methods like Visualizing and Engaging will be explained and should work as a first step to collaboratively embrace the chaos that the housing crisis brings with it.

In the winter of 2024, we had the opportunity to meet Sabeth from Urban Equipe, a key local figure in the fight against the housing crisis. Our conversation took place at ViCAFE in Altstetten, where we gathered to discuss Zurich's housing challenges. After sharing a few coffees, we explored the Letzipark area together, gaining insight into the transformation processes shaping this part of the city.

Here is an excerpt from the conversation, which was held in German. The English translation is therefore not entirely verbatim. Following the interview, we went on a walk to explore and discuss the developments in housing production in Altstetten.

Laura + Uli The housing crisis affects all of us—not just as individuals trying to find a place to live in the urban area, where it’s precarious, but also from the perspective of being a planner or an architect. I read that in Switzerland, the disparity between supply and demand is highest in Zurich, among the major cities. How does anyone even find an affordable apartment these days? Are there still apartments available on the open market?

Sabeth There are hardly any affordable apartments left on the traditional ‘“open market’”. And if there are, they’re on commercial platforms like Homegate, and they’re gone within minutes and sometimes they’re just scams, so you really have to be careful. But there are affordable apartments available in the non-profit sector. However, access to these is limited. There are often long waiting times, and in many cases, you need a small starting capital—especially with housing cooperatives.

Laura + Uli What does "a small starting capital" mean?

Sabeth If you want to sign up with cooperatives—there aren’t many you can even sign up to for anymore—you always have to pay for a membership or a share. The membership price can range from 500 to 3,000 CHF. You get it back when you leave, but if you don’t have it, you can’t get on the list. And if you get an apartment, you often need to buy share certificates. There are solidarity funds to help with this. But still, many cooperatives don’t accept new members anymore. This is especially tough for migrant populations who might not know about the cooperative system or how to sign up. Many cooperatives also have discriminatory policies or strange ideas about who they want to have in their house. There are also city-owned apartments, which are distributed very fairly—perhaps even too fairly.

Laura + Uli What does that mean?

Sabeth There’s a random selection process. The city advertises and allocates apartments weekly. They try to eliminate any perceived advantage, which also means that people with urgent needs aren’t prioritized.

Laura + Uli What’s the ratio? How many municipal apartments are available, and how many people are searching?

Sabeth I don’t know the exact current numbers. My impression is that about five to ten municipal apartments become available weekly, plus some apartments within cooperatives.For young people, there are youth housing networks, which primarily offer temporary housing for students. There’s a lot available in this sector, but it’s precarious since it’s always temporary, and you never know what comes next. I’ve also heard about issues with these networks because the two main organizations offering this have a monopoly and take advantage of their position. There’s no real alternative, so tenants can’t push back.

Laura + Uli So, where can you even find housing anymore?

Sabeth You can find apartments through your personal network, though this is criticized for being inaccessible. But it’s often the only way to keep rents lower since the apartments aren’t listed publicly but are handed over directly. People then sublet their apartments.

Laura + Uli Is there a rent cap or similar regulation in Zurich?

Sabeth There’s no rent cap in Zurich, but there’s a profit cap across Switzerland.

Laura + Uli Does that mean landlords can only make a 2% profit on rents by law?

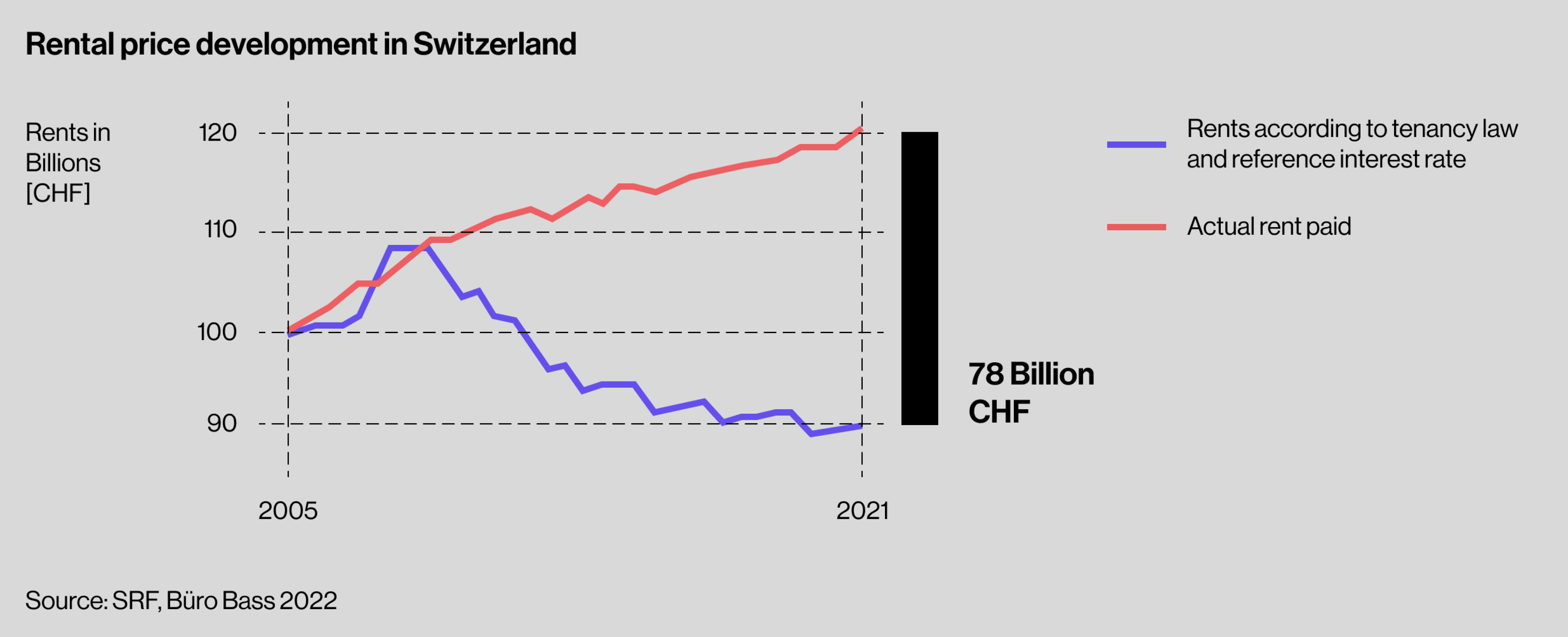

Sabeth Exactly, which is theoretically even better than a rent cap. But it’s not implemented or monitored. A study by the Tenants’ Association two to three years ago showed that too much rent is being charged because of this lack of enforcement. I don’t remember the exact figures, but on average, every tenant household is overpaying by about 370 CHF per month. All in all, that's several billion francs a year.

Laura + Uli What could be done to enforce this cap? More staff in the city or the right people in the right places?

Sabeth It’s actually quite simple. I’m not a lawyer, so I’m not sure where exactly it should be implemented, but the left has been advocating for years on a national level for regular checks—like how VAT is audited. Even small organizations get visits to check their VAT compliance. The same could be applied to landlords. For example, if you own more than three properties—or even just one since that makes you a landlord—you should be subject to periodic checks.

Laura + Uli Is there a tool tenants can use to verify if their rent is fair and legal?

Sabeth No, there isn’t. You can contest excessive rents within the first 30 days of signing a lease, but you’d have to prove it yourself. You don’t have access to the landlord’s books to see what they paid for the land or renovations. This leaves you powerless. Mediation offices or courts could be stricter in demanding transparency, but landlords often show up to negotiations without any documentation. And since you can’t force them to disclose, many challenges fail. What’s really needed are trustees who can access the books.

Laura + Uli Who are the landlords, the key actors in Zurich’s housing market? From a German perspective, I’d say it’s the private sector.

Sabeth In Zurich, about a quarter of apartments are non-profit. They’re owned by the city, cooperatives, and some foundations. The remaining 75% are roughly evenly split between private small-scale landlords and institutional investors. This balance is shifting. Last year was the first year institutional investors surpassed private landlords. It’s worrying because institutional owners rent out properties with very different intentions. Private landlords often live in the same building or run a business there, so you have a direct contact. If your landlord is Swiss Life, for instance, there’s no direct counterpart anymore, it’s just a huge player in the game. They’re profit-driven by nature and operate under partially different regulations. Cooperatives, for example, can keep the value of the land they bought 80 years ago on their books, resulting in much lower rents. But the pension funds, for example must record land values at current market prices, which drives rents up and inflates the market.

Laura + Uli In Germany, this dynamic is often driven by resale prices, allowing for ever-higher valuations. This can lead to speculative vacancies or large gaps in development as land becomes too expensive even for major developers.

Sabeth Yes, it’s absurd because it’s the same land. But if a pension fund needs to show a 5% return on its investments, and rising land values reduce this to 3%, it changes everything—even though the property itself hasn’t changed.

Housing Crisis

Access to secure and affordable housing is a fundamental aspect to secure stability in our lives, shaping our living conditions and connection to the city we inhabit. The right to housing is not only a matter of social justice but also takes on a new urgency in the face of the climate crisis, which exacerbates the pressing global housing crisis. This crisis is intricately linked to the environmental impact of housing and construction, including skyrocketing land prices, the financialization of the real estate market, migration patterns, and exploitation of resources. While affordability and access toof housing are core aspects to be considered, we must question the sustainability of our construction practices at the same time, given that the construction industry is responsible for about 40% percent of total raw material consumption and generates a staggering 88 million tons of CO2 emissions annually in Germany alone, which is around 13% of Germany’s CO2 emissions (674 million tons).

Therefore, we aim to explore contemporary housing production and its profound impact on society between economic, societal, and environmental questions of the climate crisis. We seek to redefine housing as an essential and communal good. Housing is a central societal issue that has the potential to either support or destabilize during individual crises. The same is true for the larger societal scale: housing can foster or deteriorate social cohesion on local and global scale. To understand this issue comprehensively, we will conduct international and interdisciplinary research into political and financial power dynamics, examining their influence on regional, national, and international contexts. The housing crisis, exacerbated by climate change, is one of the most pressing global challenges requiring our collective attention.

The Housing Crisis in Zurich

Zurich, like many European cities, is facing a severe housing crisis. Despite its reputation as a wealthy and safe global financial hub, the city’s housing challenges have worsened in recent last years, threatening social equity and ecological sustainability.

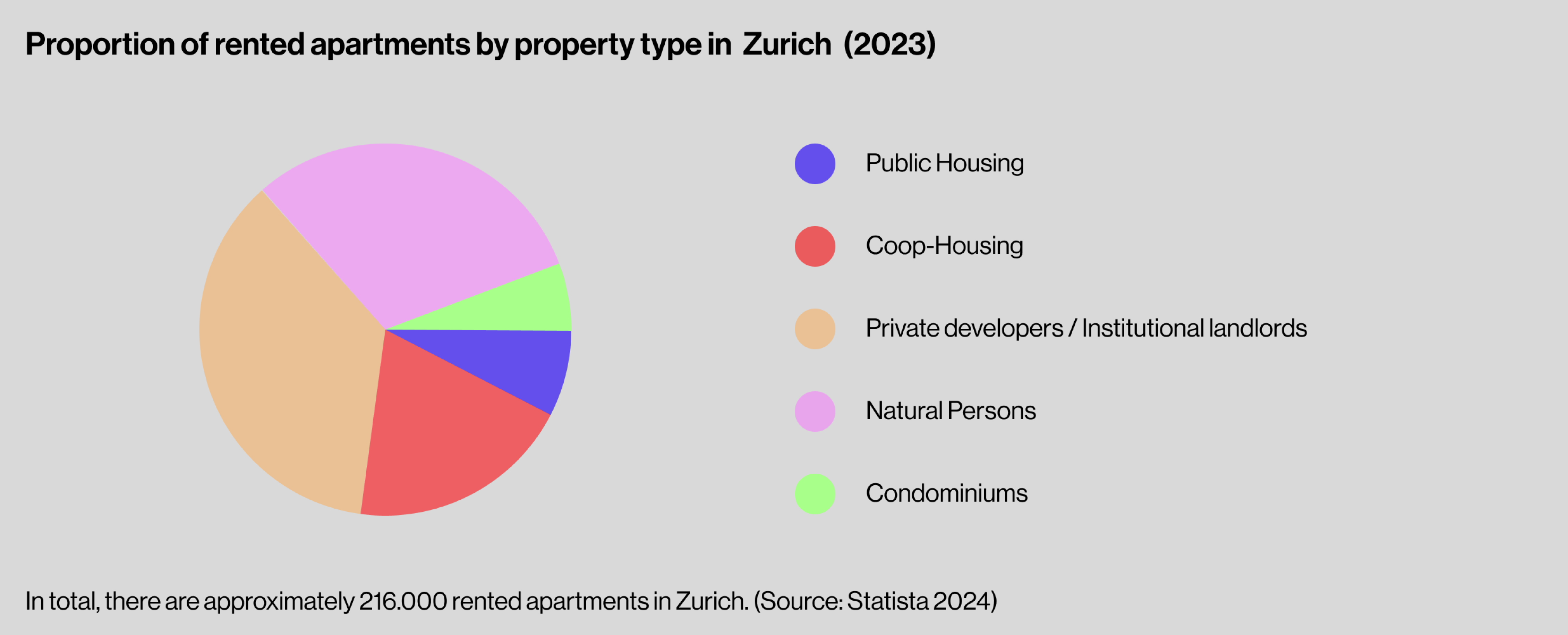

Zurich has a long tradition of cooperative housing based on the principle of “Gemeinnützigkeit” (common utility), which allows for stable, affordable rents. This model, supported by the state for municipal land allocation and mortgages, accounts for about 20% of the housing stock in Zurich. Despite this growing demand, cooperative housing has not expanded significantly in recent years. Meanwhile, private developers and institutional landlords have increased their portion of Zurich’s housing stock to 35%, pushing ownership dynamics in favor of profit-driven models—backed up by the financialized real-estate lobby, which is able to influence political decisions for their interests.

Proportion of rented apartments by property type in Zurich (2023)

Rising rents compound the problem. Swiss law caps rental profits at 2%, but lax enforcement and legal loopholes allow many landlords to exceed this limit. Between 2000 and 2021, rents in Zurich rose by more than 60%. In 2021, people in Switzerland paid 78 billion Swiss Francs more in rent than they should have. The situation is especially affecting marginalized groups like migrants, who earn less, live in poorer conditions, and even pay 10% more rent on average than non-migrants. These rent hikes deepen socio-economic divides, making the city increasingly unaffordable for specific groups of residents.

Rental price development in Switzerland

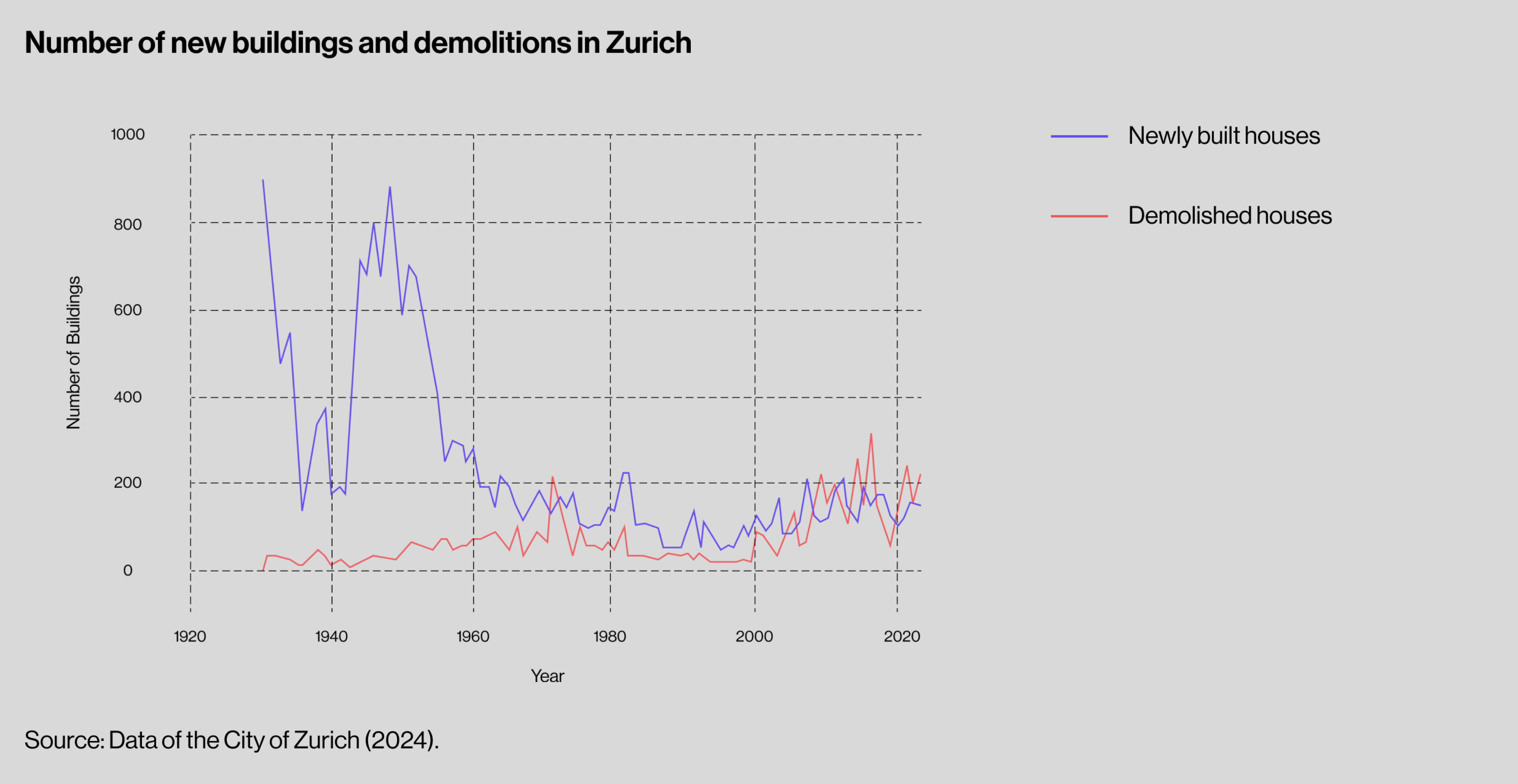

The proposed solution to fight the increase in rents is directly linked with the ecological crisis. One paradigm to overcome the housing shortage according to developers is “bauen, bauen, bauen!”, which is further exacerbated by the demolition of older housing stock and replacement with new buildings—the “Ersatzneubauten”. The settlements are often owned by institutional developers. The redevelopments are fostering gentrification processes and lead to the loss of grey energy affecting people and the environment. For example, in the Altstetten neighborhood, plans to replace 317 flats with 367 new ones will displace 735 tenants, most of whom cannot afford the higher rents in the new buildings. Alternatives, such as adding floors to existing structures, could achieve densification while minimizing social and ecological costs. This pushes displaced residents to the suburbs, increasing commuting times, transport costs, carbon emissions and harming the social inclusion in the city. Furthermore, the demolition increases the waste of resources like building materials and causes more CO2-emissions/grey emissions than building within the existing.

“Number of new buildings and demolitions in Zurich” // Description: Based on data from the City of Zurich, you can see that the demolition of the existing housing stock has been increasing compared to previous decades.

Zurich’s housing crisis reflects the complex interconnection of challenges at hand: the decline of cooperative housing expansion, and the prioritization of profits over social and ecological needs. Addressing these issues will require stronger enforcement of rent controls, support for non-profit housing, and collaborative urban planning that balances densification with affordability. Without decisive action, Zurich risks becoming a city accessible only to the privileged few.

Working through the crisis together

Our theme is "working through a crisis together." Even though we understand that we won't completely solve the housing crisis, collaborating on the issue collectively and seeking to comprehend it together can generate transformational energy. To embrace the chaos, we need to envision a set of methods that, on one hand, emphasize the discovery of a collective language and understanding for the crises we experience. And, at the same time, ensure that we don't lose sight of the goal of fostering the ability to participate in strategic change processes.

Through collaborative efforts, we want to make complex, formal, and informal data more accessible. Finally, through knowledge sharing, we want to establish an open-source knowledge network, to equip communities with tools to navigate this global crisis sustainably together.

Why methods matter

In the face of increasingly complex and interconnected challenges facing the polycrisis with all its multilayered problems, transdisciplinary and multi effective methods and tools are essential. They enable us to move beyond the limitations of single disciplines and approaches and foster collaboration across diverse fields. These methods provide tools to navigate uncertainty, bridge theoretical and practical divides, and engage with the complexity of our current crisis moment. By attempting different approaches of collecting information, making them visible, audible and even perceptible we aim to lower barriers and include more voices. Moreover, embracing a multiplicity of methods and learning from various perspectives can help us overcome social boundaries, fostering greater inclusivity and shared understanding across communities.

Visualizing—Mapping as a Method

We use mapping as a creative and emotional tool, helping to re-trace memories, capture feelings connected to a place, and make sense of personal experiences. Mapping can also unintentionally exclude or misrepresent diverse perspectives due to accessibility issues, cultural unfamiliarity, or lack of digital literacy. Additionally, maps often omit realities not considered mainstream or commercially valuable, such as marginalized communities or hidden local gems. Maps can also cause harm, such as exposing vulnerable areas to exploitation or tourism, or being overly abstract, making them hard to interpret without specific cultural or technical knowledge.

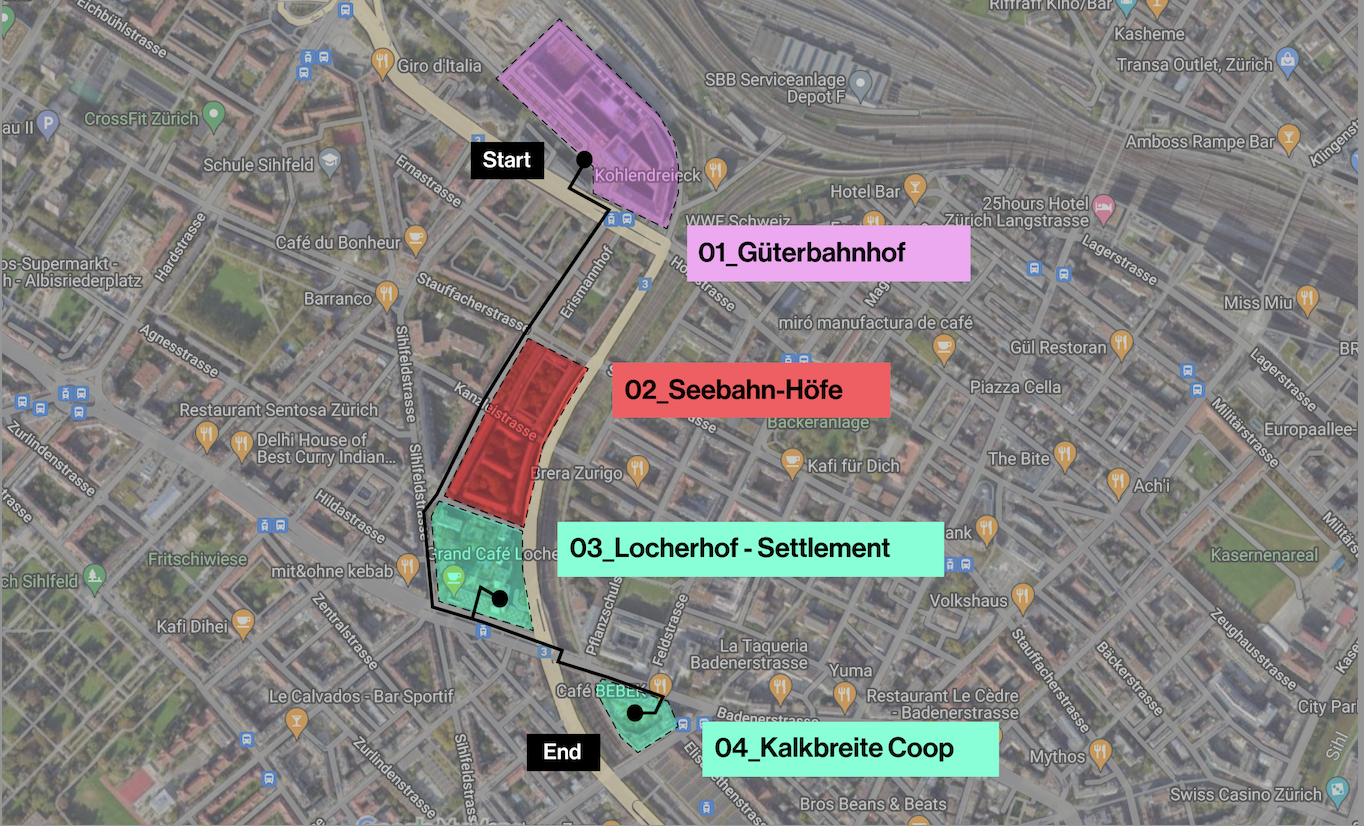

Mapping can be used as a low threshold powerful tool for analyzing Zurich's housing crisis, as it helps to untangle the complexities of the built environment and the many stakeholders involved. By visually displaying spatial knowledge, existing structures, and power dynamics, mapping not only reflects current realities but also offers new insights and reinterpretations of urban space. It helps not only to make sense of the chaos but also to navigate and embrace it. In June 2024, we explored various locations in Zurich as spaces for learning and knowledge within the context of the housing crisis. We discovered that space is, once again, described and perceived subjectively across disciplines.

Walking Tour” // Description: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1bKM98z7K_PKRwE1CsqXXF8kkVdUTUJQ&usp=sharing

Engaging

We asked ourselves: How can we uncover information that isn’t immediately visible but remains hidden beneath the surface? Entering different spaces of crisis, we aim to engage meaningfully with the people who navigate them daily. To better understand the housing crisis in Zurich and explore ways to combat it, we initiated a dynamic and ongoing process of dialogue, inviting diverse individuals to share their perspectives and experiences. Although we've already met Sabeth, we will continue our journey in spring 2025, engaging in workshops and talks to discuss formats, solutions, tools, and methods across stakeholder boundaries.

Sources / Knowledge Pool

COLLECTIVE MAP

https://maps.app.goo.gl/1AyMTc7oV5QMGQnx8 BOOKS

Mehr als Wohnen – Genossenschaftlich planen - Ein Modellfall aus Zürich Margrit Hugentobler, Andreas Hofer, Pia Simmendinger Haushälterische Bodennutzung vollziehen Sibylle Wälty Cooperative Conditions – A Primer on Architecture, Finance and Regulation in ZurichAnne Kockelkorn; Susanne Schindler; Rebekka Hirschberg Wer besitzt unsere Häuser? Mieten-Marta Mietenwahnsinn? Nicht mit uns. Wir wollen bleiben. Stadt für Alle; Mieten-Marta

ACTORS

CH https://alleswirdbesetzt.ch/ @alles.wird.besetzthttps://mieten-marta.ch/ @mietenmarta https://www.urban-equipe.ch/ @urbanequipehttps://www.zas.life/ https://tsri.ch/ https://www.seebahnhoefe-retten.ch/

Global https://darkmatterlabs.org https://spaceforfuture.org and many more

CONTENT

House’ it going Collective Google Map Der KOMPLEX Lochergut Zürich [DE Video] https://diegutenachricht.ch/statistiken/ Zurich Commons Cooperative Conditions Stadtentwicklung ZürichNexus Podcast Kontextur PodcastFuture Histories Podcast

SPACES

https://zentralwaescherei.space/ https://streikhaus.ch/ https://post.zureich.rip/ https://gessnerallee.ch/ https://www.helsinkiklub.ch/ https://www.dynamo.ch/ and many more

OUTLOOK Panel with Stakeholders @ Now what/What if - Spring 2025House’ it going? Workshop – Spring 2025

Question for the next LAB:

How can embrace chaos within the broader context of the polycrisis inspire new strategies to address the housing crisis?

Laura Margarete Bertelt

Laura (she/her) studied architecture in Dusseldorf and Milan. She is currently deepening her interest in democratic (planning) processes in the postgraduate Master's program Urban Studies at Bauhaus University Weimar.

Angelika Hinterbrandner

Angelika (she/her) engages in diverse roles and formats within the field of architecture.

Ulrich Kneisl

Ulrich, (he/him) is an architect who is currently working on the transformation of existing buildings with the focus on housing.