What resources are needed in order to enter into mentoring relationships?

Mentoring as a Practice

- [2025]

- Nora Sobbe

How are mentoring relationships initiated?

What role do differences in experience play in this form of relationship – or can they be understood as peer-to-peer encounters?

How does group mentoring differ from one-on-one mentoring situations?

How do mentoring relationships relate to other social forms such as friendship, partnership, or (chosen) family? Could mentoring perhaps be understood as a conversational mode that friendships, partnerships, and other relationships may temporarily adopt? Or does mentoring extend beyond the moment of speaking?

Do mentoring relationships serve a broader purpose that exceeds the one-on-one encounter?

For the last three years, I have studied in the Master of Transdisciplinary Studies at Zurich University of the Arts, where mentoring is embedded in the study structure as a module and is thus an integral part of everyday study. I began to take an interest in this format, sparked by brief moments of hesitation or pausing during mentoring sessions. For example, I asked myself whether I should return the often initially posed question, ‘How are you?’, to my mentors. Would doing so perhaps undermine the directedness of the conversation that is meant to be maintained? I wanted to explore the specificity of this form of relationship or encounter, but without stopping at my own mentoring experiences. So, I turned to three further contexts in which mentoring or mentoring-like relational forms are practiced and discussed. From these, I worked out similarities-in-difference and, in doing so, generated three motifs that guided my reflection on my own mentoring experiences: #Reciprocity, #Authority/Measure, and #Transformation.

As a first context, I included the mentoring program Berufsziel: Professor*in an einer Kunsthochschule in my reflections. The program was initiated in 2002 by Sigrid Haase (then Women’s Representative at the Berlin University of the Arts) and still runs today under the name Prof*me1. This program can be counted among those contexts where mentoring is used as a personnel development tool in the field of gender equality. The first five cycles of the program were extensively evaluated, and this evaluation was published.2 Here, mentoring is repeatedly described as a #Reciprocity between mentee and mentor: mentees could expand their networks, while mentors received impulses for their work from so-called junior academics. This #Reciprocity is also discussed in terms of institutional benefit: joint projects between mentees and mentors are thought to ultimately benefit students through improved teaching quality. At the same time, mentoring relationships are seen as opportunities to exchange ideas “abseits von institutionellen Zwängen [outside of institutional constraints]” including reflections on “mit welcher Haltung [...] man den Hochschulen begegnen will [the attitude one wants to take in engaging with universities]”.3

As a second context, I turned to the project The Hologram, which, based on experiences with the U.S. healthcare system, opposes the economization of healthcare and proposes alternative care constellations alongside professional healthcare. The project was initiated in 2016 by artist/activist Cassie Thornton, with considerations published in 2020 in The Hologram: Feminist, Peer-to-Peer Health for a Post-Pandemic Future.4 I see parallels to mentoring in the directedness of the conversations that take place within these care constellations: a triangle of three caregivers tends to the health of a fourth person – the hologram. These constellations are presented as a peer-to-peer protocol, with the relationships explicitly characterized by a distancing from #Authority and expertise.

As a third context, I examined reflections from Italian difference feminism of the 1980s, which addressed a relational form among women* in which one woman* entrusts herself to another woman* who embodies a “more” for her.5 These affidamento relationships are introduced as relationships initiated through an act of #Authority attribution. Unlike in The Hologram, here there is no turning away from #Authority. Instead, an understanding of authority is proposed that distances itself from hierarchy and power. The difference feminists developed this understanding of authority starting from the mother-daughter relationship. In affidamento relationships, they saw an opportunity to enable women* to participate in society without orienting themselves toward male mediating instances, allowing them to relate to the world in a way that brings forth female difference.

Each of the three examined contexts frames mentoring or mentoring-like relationships under an overarching goal or as the starting point of socially transformative processes (#Transformation). While The Hologram is presented as a “social technology for dehabituating humans from capitalism”, Italian difference feminism seeks to grant women* a social existence without requiring adaptation to patriarchal structures. The mentoring program Berufsziel: Professorin an einer Kunsthochschule promises improved teaching quality and simultaneously frames mentoring relationships as spaces for reflecting on university structures. I am asking whether finding ways to hold the openness of shaping the mentoring format in the context of an art academy carries transformative potential by opening up a space in which experimenting with how learning together at a university is envisioned can take place.

As a prerequisite for holding the openness of mentoring, I see the ability to draw on a broad pool of statements, questions, gestures, and methods associated with the practice. This is where I begin with a process of object design. I have conceived an object that initiates the circulation of experiences, statements, questions, and methods from one-to-one mentoring sessions and invites participants to collectively enact and shape mentoring as a practice. The object, in a way, materializes an implicit recourse to prior understandings of mentoring – an appropriation of statements, questions, gestures, and methods associated with it – while at the same time inviting the extension of this shared pool.

note-spitting mechanism

concept object: Nora Sobbe realization object: Johannes Reck, Marcel Rickli photo: ©Marcel Rickli

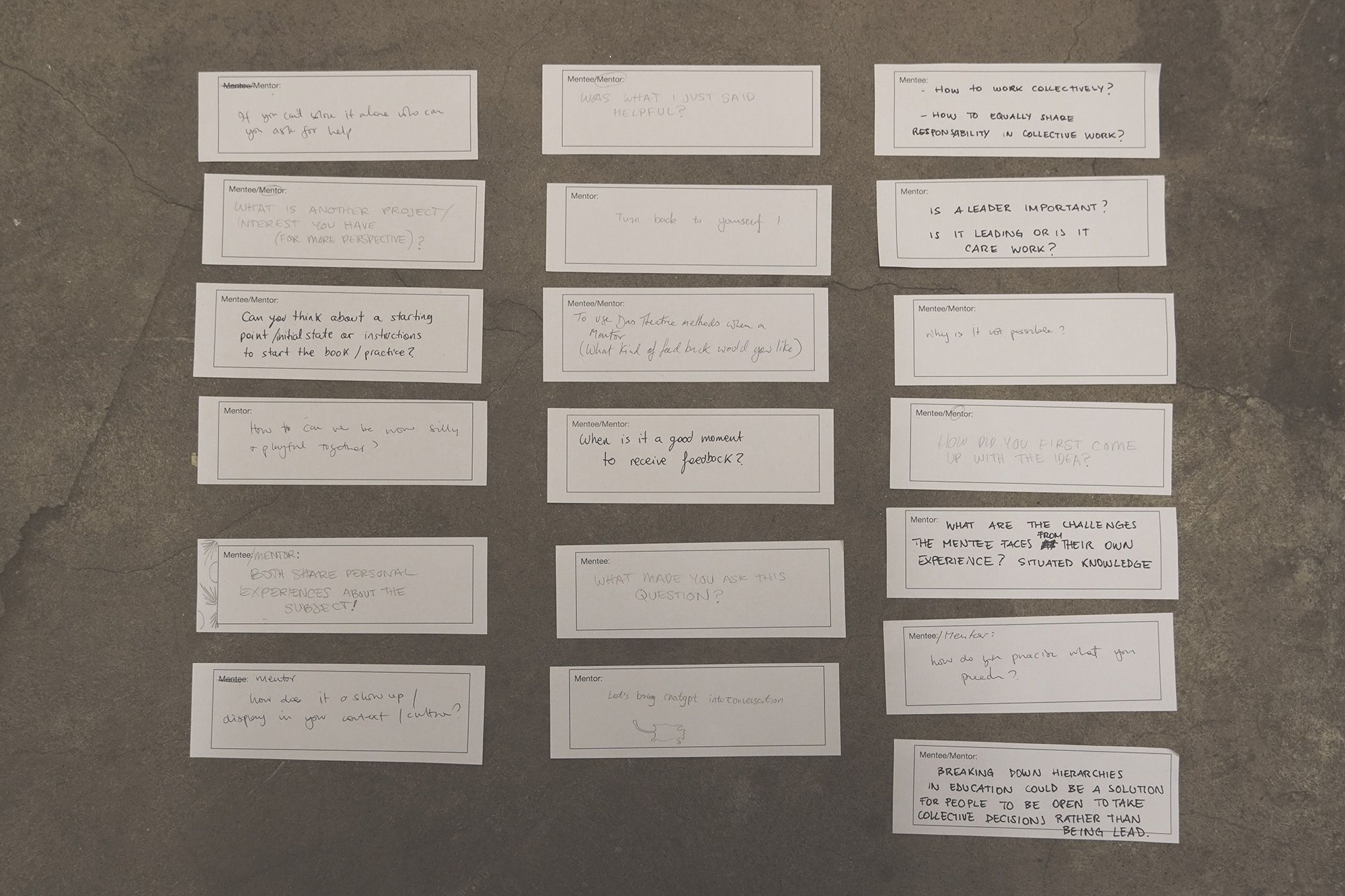

The object – a note-spitting machine – is positioned during mentoring sessions between the mentee (A) and the mentor (B) and spits out notes at defined time intervals (with a random range) in the direction of A/B. The notes contain statements and questions. A or B is invited to read the note aloud to their counterpart: as an offer for interaction; by distancing themselves from it and thereby updating the mentoring setting as it exists; etc. Crucial for the setting is a feeding station, which generates the pool of statements and questions from which the object randomly selects notes. Mentees and mentors are invited to write down statements/questions they would have liked to say/ask in a mentoring session; to note actions waiting to be realized within a mentoring session (“I actually would have liked to record the conversation.”); to note actions/gestures that could become a method (“I brought strawberries from my neighbor’s garden, just take some!”). The notes can be assigned to one of the two positions (A or B) or saved under the category “A/B”: here the object randomly decides whether the statement/question will be spat in the direction of A/B in upcoming mentoring sessions.

notes collected in a workshop within the SoC Cohort 2025/2026

Haase, Sigrid (Hg.), Musen Mythen Mentoring, XII. Berlin 2011.

Ibid.

Thornton, Cassie, The Hologram. Feminist, Peer-to-Peer Health for a Post-Pandemic Future, London 2020.

I have primarily worked with the following publications:Libreria delle donne di Milano, Wie weibliche Freiheit entsteht. Eine neue politische Praxis, 1. Aufl., Berlin 1988. Muraro, Luisa, Nicht alles lässt sich lehren, 1. Aufl., Rüsselsheim 2015.

Nora Sobbe

Nora reacts to specific social situations through object-design processes that invite exploration of social interactions which may initially feel familiar.

SoC Gathering, 2025

04.07.2025 — 06.07.2025

Reflecting on the SoC Gathering this past week at Zurich University of the Arts. Find out more