There, There: body

In-between

On November 1, 2023, I disembarked from the plane onto the warm asphalt of Rio de Janeiro's airport, instantly enveloped by a wave of moist air. The swift transition, occurring within the span of fifteen-hour travel, caught me off guard. Berlin's impending winter had been abruptly replaced by Brazilian spring. What struck me upon landing in Brazil was the realization that my body and mind operated in different places and were both driven by the illusory boundaries of embodied memory. Even immersed in the warm embrace of this new place, my mind and body still clung to the memory of space and time in Berlin. Adjusting took a while, despite the abruptness of the transition, as I had slept through most of the flight. Consequently, memory, as a deeply ingrained phenomenon that triggers the present, carried traces of the past into the current state, concealed within the vessel of my body, unbeknownst to me. I was yet to discover how profoundly touching and memory-evoking many of the experiences in Brazil would turn out to be, bridging the gap between my professional and personal life, between home and the world around me, the past and the present.

While my journey was primarily for work, I constantly reminded myself throughout the month I spent in Brazil that the opportunity to explore diverse contexts and cultures, uncovering disparities and similarities between my current and previous places of residence, was the greatest gift one could hope for. I consider myself fortunate to have encountered numerous occasions to do so. The moments when my thoughts involuntarily wandered to Kazakhstan, revealing unexpected findings and observations, didn't keep me waiting for long.

Triggers

Central Asia and Latin America – what possible connections could exist between these two places for me? Born in Kazakhstan and new to Brazil – I had never imagined that I could travel across the ocean to see the land that I have mostly heard about on the screen of television (soap operas and football matches). It seemed that those two parts of the world appear diametrically opposed, sharing little in common. Politically, Kazakhstan continues to grapple with the bitter taste of socialism. It was once hosting some of the largest Stalinist labor camps in Soviet history where numerous dissidents of the Soviet state, including professors, artists, and other non-conformist compatriots, met their tragic end. In contrast, Brazil's intellectual, cultural, and artistic circles continue to uphold communist ideals in the present, echoing communist slogans in their pursuit of a more egalitarian society, knowing the hardships under dictatorships that prevented communist ideas from fulfilling in the 20th century.

Conversations with practitioners who quoted Trotsky and espoused communist thoughts transported me back to the late 1980s when the Soviet Union's economy was in dire straits, forcing people to endure hours-long queues for meager soup bones. My grandfather, a staunch opponent of the Soviet regime, was no exception to this hardship. The poverty and desperation that followed the collapse of the once-unassailable Soviet Union, coupled with Kazakhstan's newfound independence amid the chaos of economic collapse and the rise of criminal gangs in Almaty, where I spent my childhood, left my family embittered and isolated, struggling to adapt in a rapidly changing world.

They lost the opportunity to complete their education, as the institutions they once relied upon had vanished in the wake of the crumbling Soviet paradigm and all their minimal savings vanishing in the oblivion of the “free fall” economy. Among my family, only my grandfather, who had lost his family due to Soviet repressions and had ended up in Kazakhstan due to persecution by the Soviet state, found solace in the demise of a world built on false promises. The rest of my family, even today, remains nostalgic for the Soviet past, finding it difficult to critically reflect on the fact that, despite being a victorious nation in WWII, their stability was always intertwined with repressions, prolonged periods of extreme poverty, and severe limitations. "Everyone led this lifestyle," my mother explains, recounting how poverty compelled them, after the victory in WWII, to engage in communal cooking and dining as the Soviet Union expanded its territories and took on new territories to rebuild. To this day, she cannot comprehend or forgive that the victorious Soviet nation lived in worse conditions than those who had lost the war.

In stark contrast, Brazil's intellectual elite and cultural practitioners consistently drew upon the ideals of communism and socialism throughout my journey. The works of Augusto Boal and Paulo Freire, spanning the realms of pedagogy, theater, and socio-political discourse, have been deeply influenced by communist ideas and drive social activists and socially engaged artists' work to this day. While I found these egalitarian ideals compelling and deeply inspiring, each subsequent quote from Bolshevik ideology stirred within me alternating waves of tension and anxiety.

"I must remember," I told myself, "this trip isn't about me; it's about understanding a different context." This mantra played in my mind as I listened to the promises of unwavering stability, equality, and prosperity that, on the territory of my motherland, had ensnared millions as victims, and in another part of the world—served as an example.

Despite my own haunting past, I diligently documented, photographed, and took notes on the intricate tapestry of realities that Brazil has unraveled. Its remarkable persistence in using public spaces as platforms for political and cultural resistance left a lasting impression and a series of as-yet-untranscribed materials awaits its moment to be understood and reflected upon. A lot of my research has to do with notions of care, maintenance, social reproduction, affective work, and solidarity. It also has to do with hope and work towards cultivating hope through action.

With my return to Berlin, overwhelmed with the trip and encountered experiences, I felt an intense urge to document and preserve the traces of my family's narrative during the Soviet regime, to speak to my mom more often, and to connect with groups focused on decolonial thinking and Central Asian history and culture. I want to reflect on the contradictions instigated by my research trip – the multifaceted realities of its people, and my own painful experiences and reflections. The deepest personal discovery was of that omnipresent feeling of in-betweenness: between the past and the present, between the present and the future, between the rational and emotional, remembered and imagined was yet to come. The memory that is kept in my body proved to hold tremendous power over me, and contemplations of the role of the body, the capacity of it to be swept away by thoughts and drawing me deeper into this in-betweenness of places, states of mind, and positions.

Present (and) Tense

Memory is a curious concept, resembling an elusive, dream-like state that coexists with the sharp awareness of a fully functioning rational mind. It has the power to reshape our perception of reality, allowing primal bodily functions to momentarily override rational thought. The lymphatic system "remembers" for the sake of survival. With an instant change of circumstances, the heartbeat quickens, and blood rushes to the skin, altering its hue. We revert to childlike instincts – fight, flight, or freeze – when confronted with situations that trigger specific bodily responses. Often, these reactions happen so swiftly and automatically that we scarcely notice them. However, in many instances, the environments we encounter transport us to an illusory realm – a world of "remembered" or “imagined” sites where the past gradually envelops us. Countless times, our bodies react to our surroundings over moments, hours, days, weeks, or even years, making memory the meeting point between the past and the present, transcending geographical boundaries.

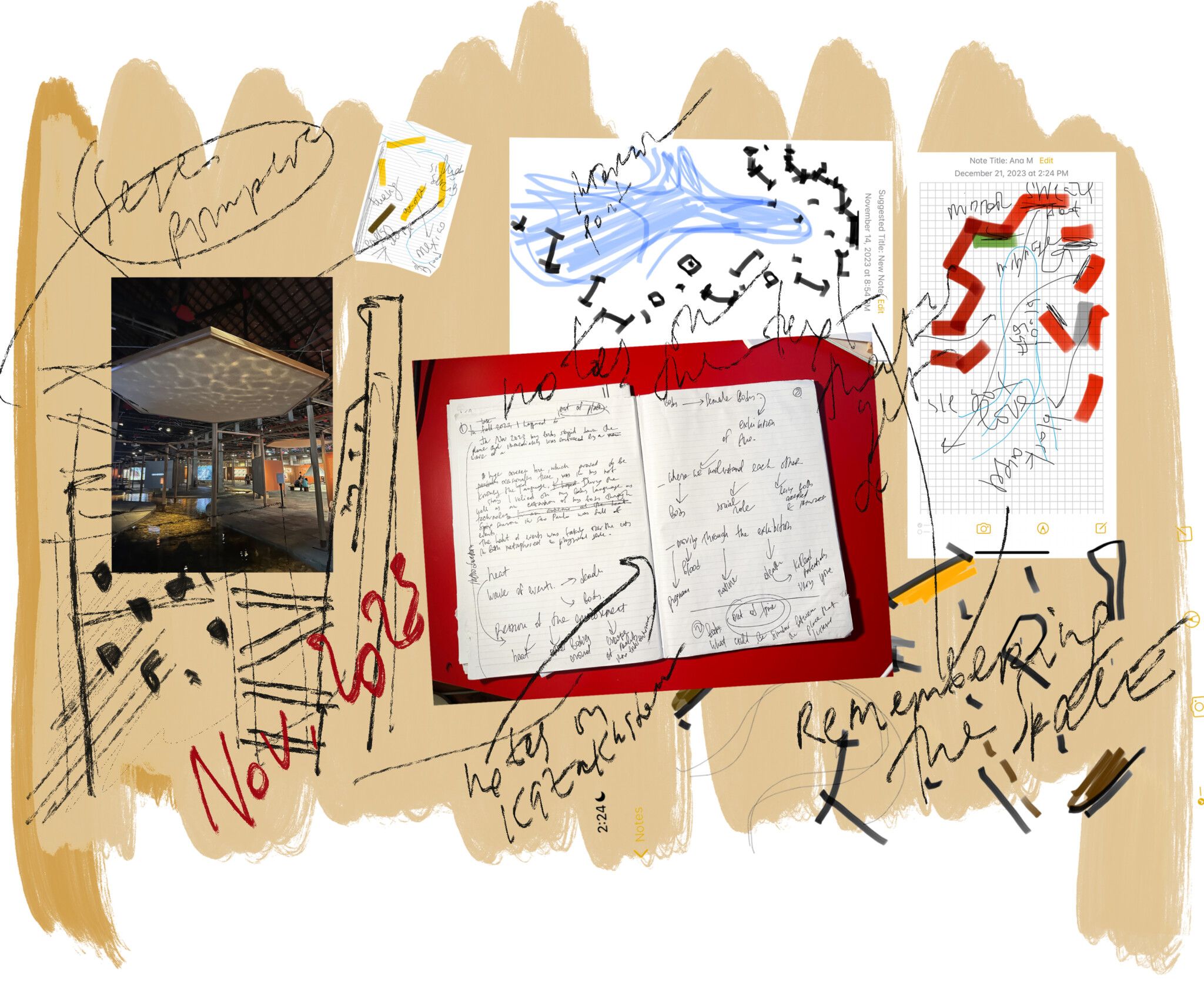

On the afternoon of November 14, 2023, accompanied by my colleague, we stepped into São Paulo's SESC Pompéia. This red-brick structure, once a drum factory dating back to the 1920s, had been transformed into the SESC Pompéia Factory by the acclaimed female Modernist architect Lina Bo Bardi. Today, it serves as a community center with a multitude of public amenities – art spaces, theaters, workshop areas, libraries and reading rooms, a swimming pool, an affordable restaurant, and extensive public spaces for recreational use. My sense of amazement upon encountering this expansive architectural and social facility stemmed from the stark absence of anything comparable in Kazakhstan. I have never heard of a well-functioning community center that serves many functions and caters to the needs of both – cultural workers and citizens. Perhaps SESC (which stands for Serviço Social do Comércio, Portuguese for Social Service of Commerce) is a unique institution in the realm of arts and culture. Being a Brazilian non-profit private institution supported by businessmen involved in trade, goods, services, and tourism and while primarily serving their employees, SESC also provides public access to numerous facilities and offers public space for culture. Remarkably, it stands as a leading institution in arts financing in Brazil, funded by a corporate tax ranging from 0.2% to 2.5%. Visiting it, I thought to myself: “How great it would have been to have one of these in Kazakhstan…”

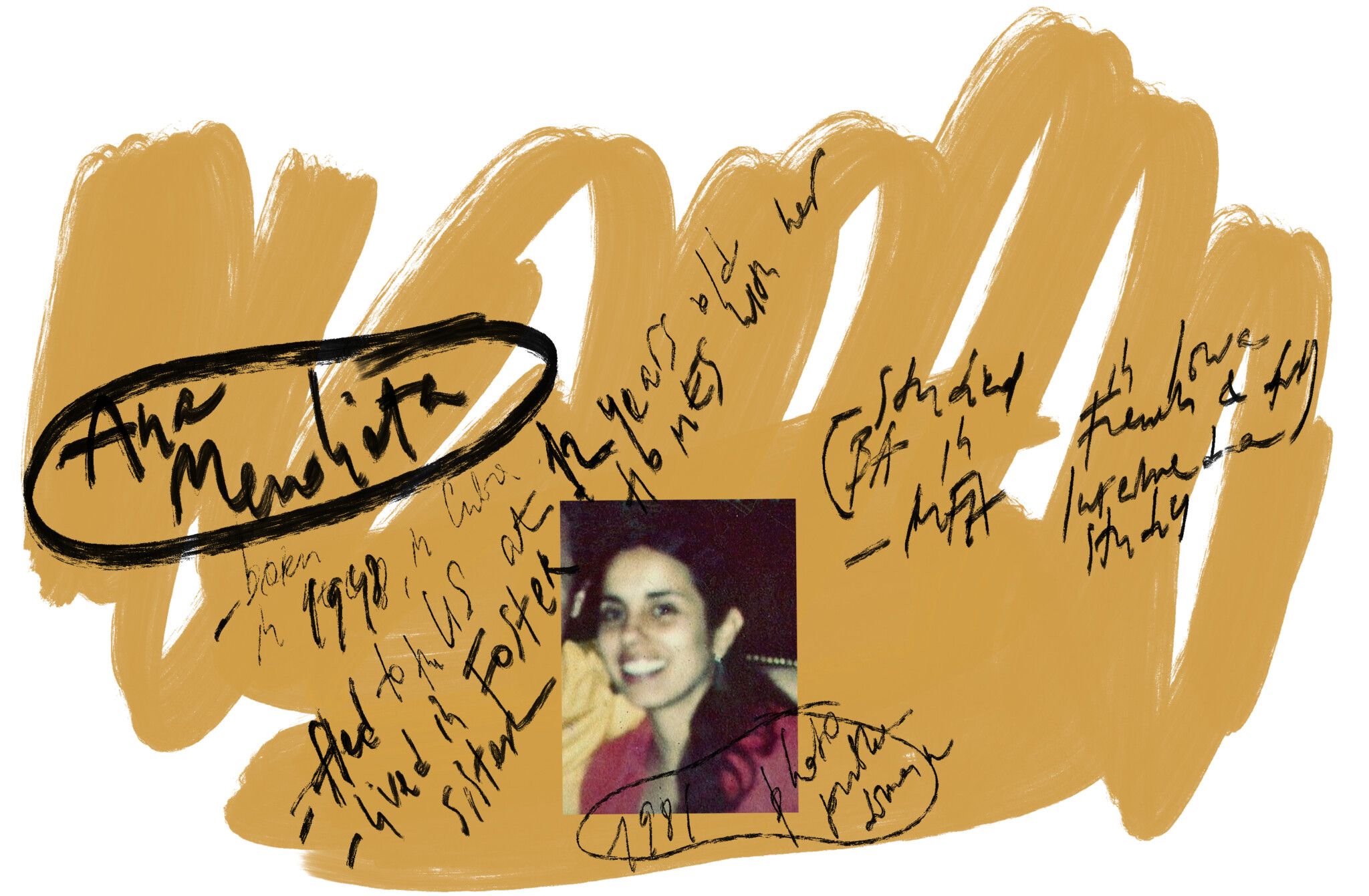

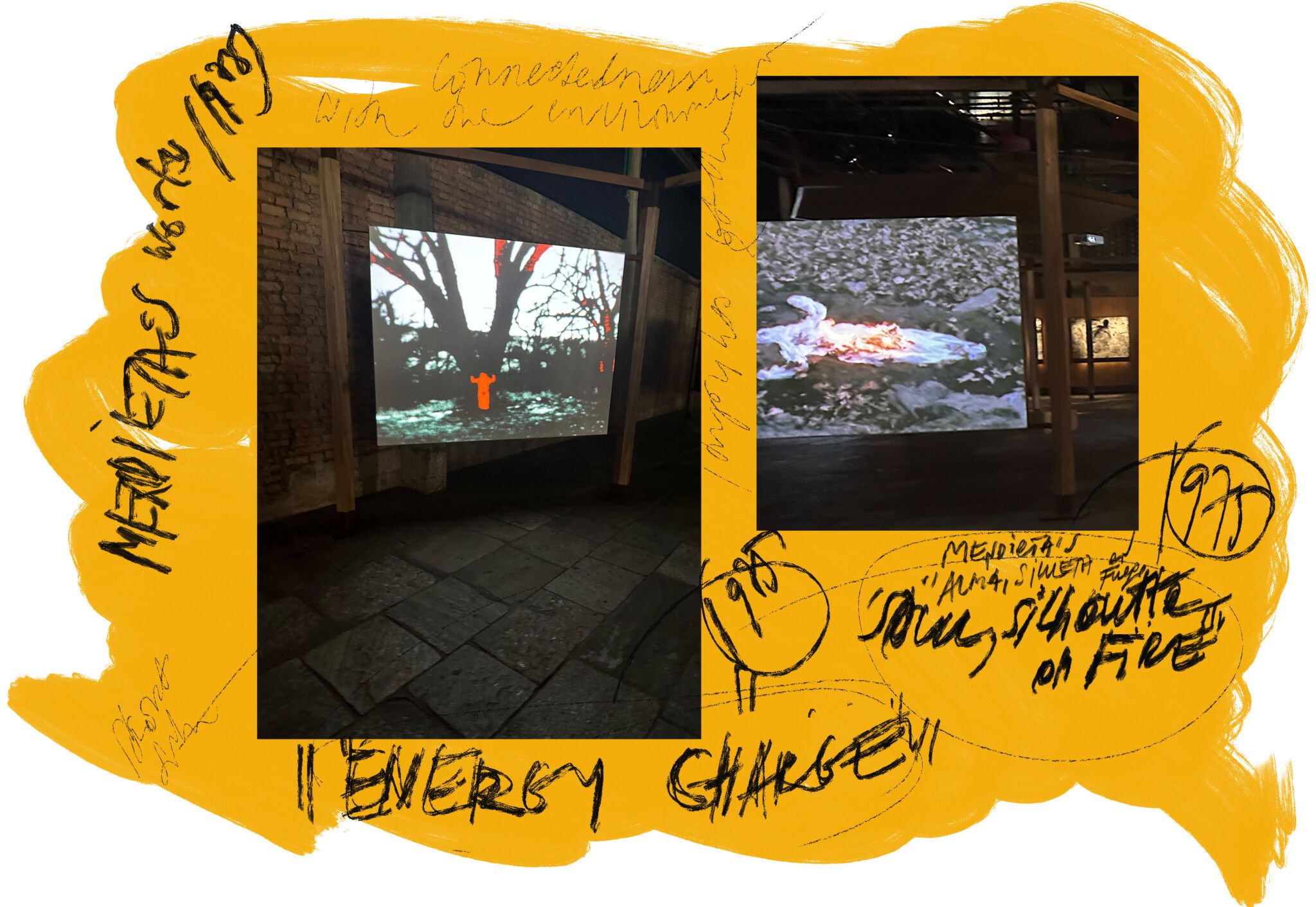

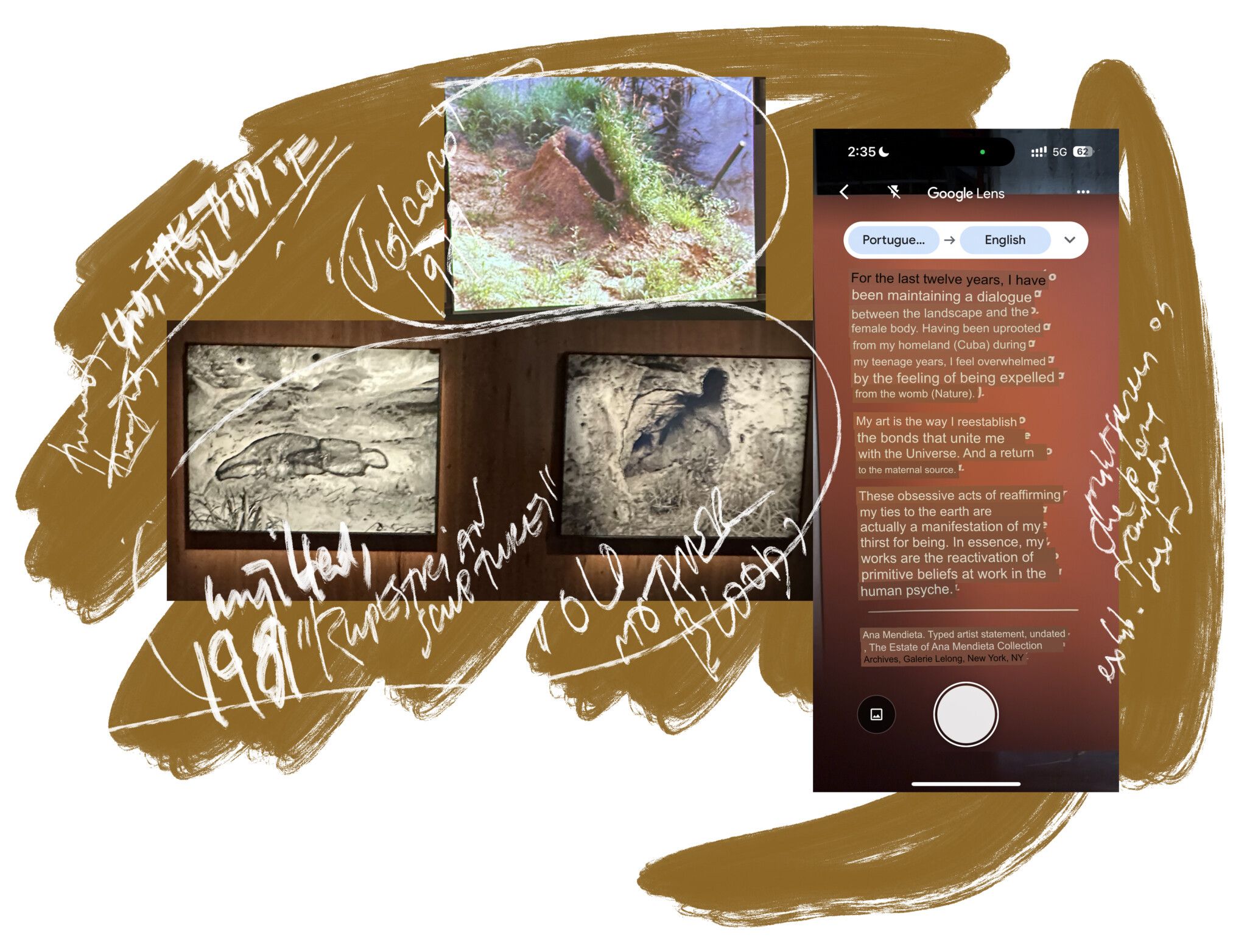

The aim of visiting SESC was to explore an exhibition by the Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta (1948-1985). The exhibition featured an extensive collection of the artist's film performances, recorded on Super 8, 16 mm, and Betacam between 1972 and 1981. (SESC, 2023) It also showcased several series of self-performative photographs. Curated by Daniela Labra, co-curated by Hilda de Paulo, and assisted by Maíra de Freitas, the exhibition, titled "Ana Mendieta: Silhueta em Fogo," (transl. “Ana Mendieta: Silhouette on Fire”) provided an insightful overview of the life and work of one of contemporary art's most iconic and yet mysterious figures.)

Fig.1 Notes - Mendieta’s show: Visiting Ana Mendieta's show at the SESC Pompéia in Brazil, making notes. Collage with notes by the author (2023)

Fig.2 Ana Mendieta - Image from the public domain (WIKI Commons); Collage with notes by the author (2023)

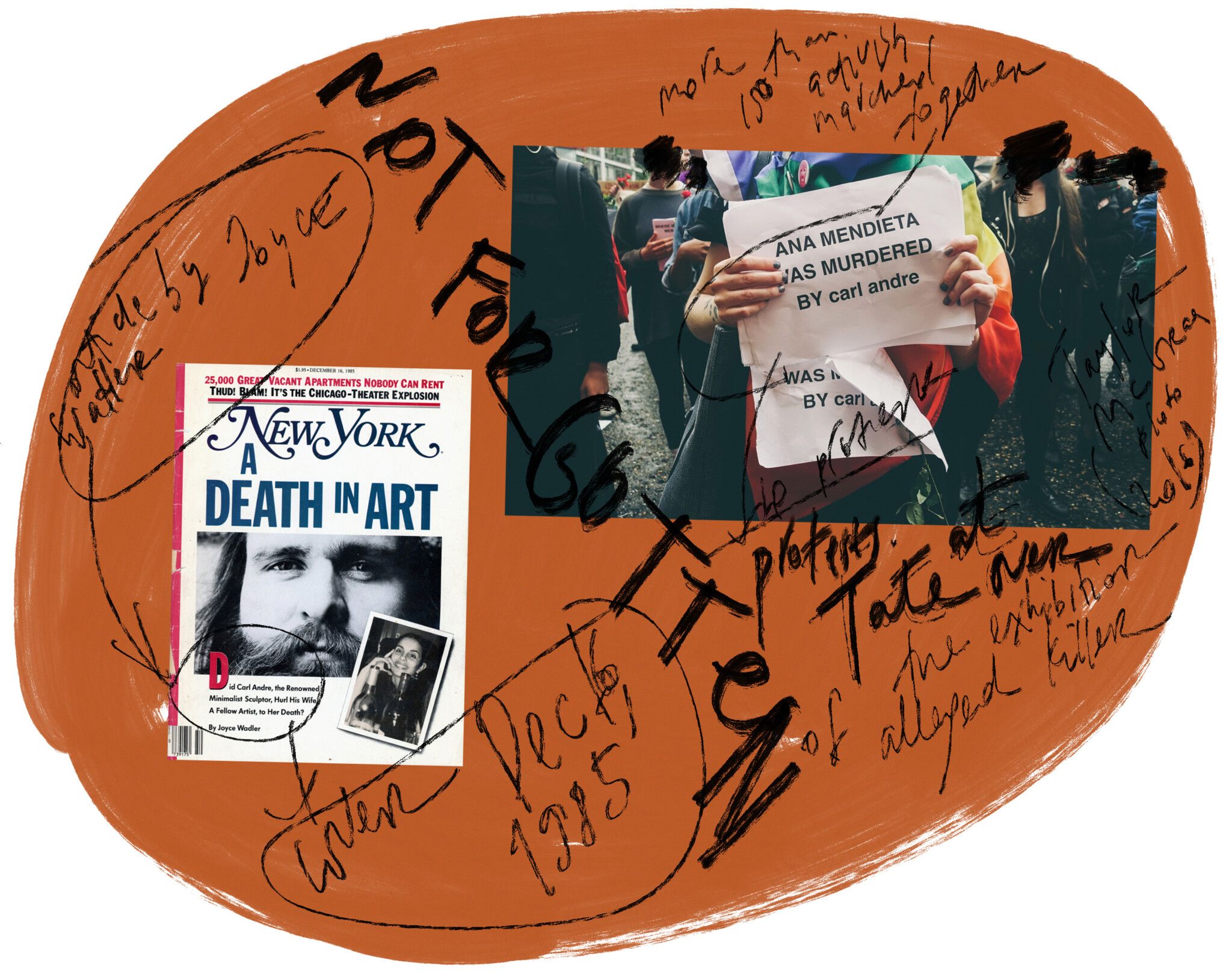

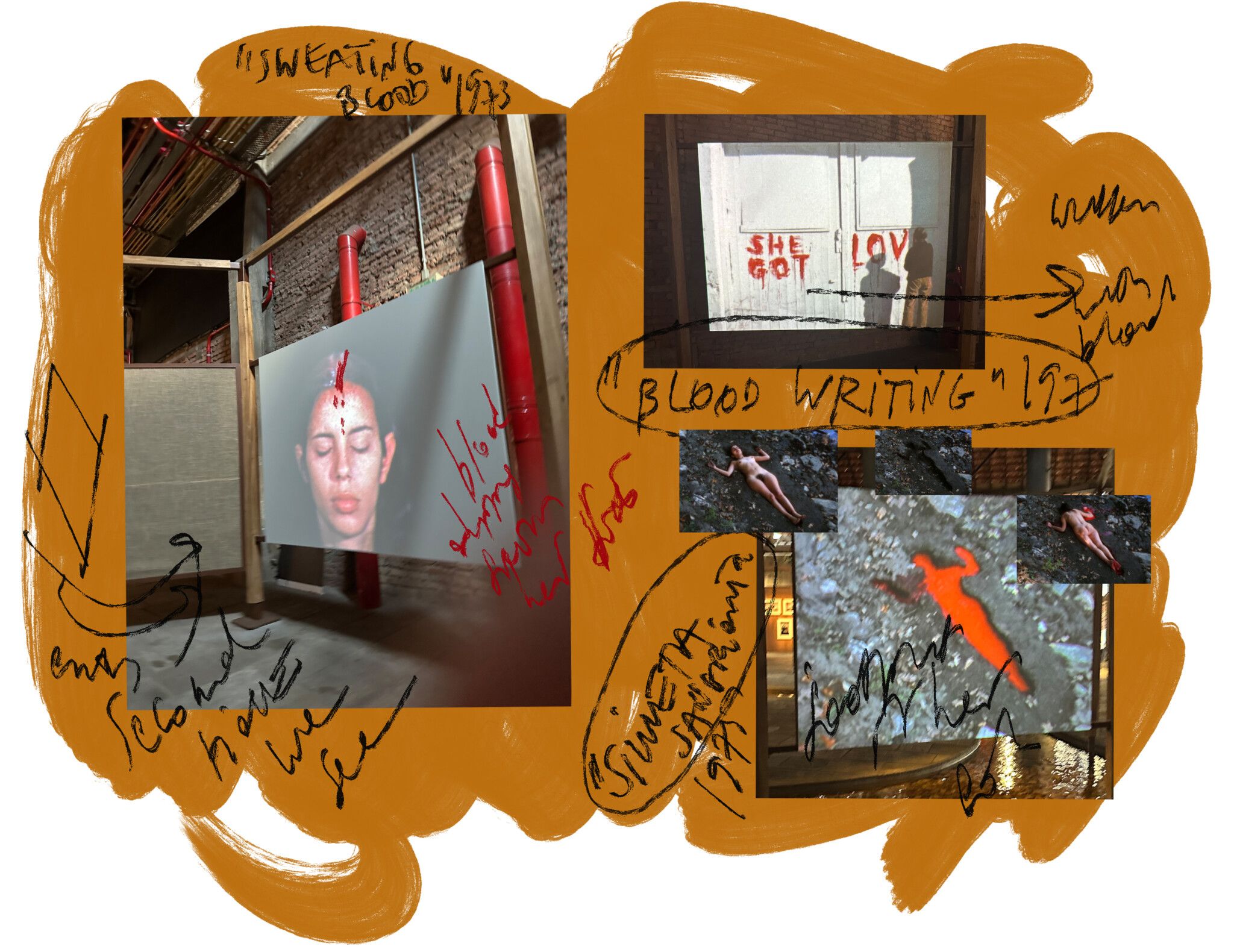

As we entered the exhibition space, divided by partitions, I immediately noticed numerous nude figures on the screens. Each of these images documented the artist's female body or depicted the footprints and traces she left on various surfaces around the world, many of them in blood-red hues. At that moment, my colleague whispered in my ear that the artist had died young. The mystery surrounding her tragic fall from her 34th-floor New York apartment in 1985 remained unresolved, with family and friends speculating about her partner, minimalist sculptor Carl Andre's involvement. Many believed he had pushed or thrown her out of the window during a drunken argument. (O’Hagan 2018)

Fig.3 Mendia’s death.- Cover sourced from Gallery98 website: Cover photograph of Andre by Gianfranco Gorgoni; photograph of Mendieta by Wendy Evans; Photography of the protests at Tate by Taylor McGraa, published on Dazed Digital (June 2016). Collage with notes by the author (2023)

Fig. 4 "Blood" - Mendieta’s works presented at SESC (left to write): “Sweating Blood,” 1973, single channel, super-8mm film transferred to high-definition digital media, color, silent; 03:18 min., “Blood Writing,” 1974. Super 8 film, color, silent., Silueta Sangrienta, 1975. Super-8mm film transferred to high-definition digital media, color, silent, 1:51 minutes. All images are copyrighted by The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong. Collage with notes by the author (2023)

This snippet of information from my colleague arrived at a disconcerting time and place.

On November 14, just two days prior, I had been grappling with the distressing news from Kazakhstan. On November 12, the former Minister of National Economy, Kuandyk Bishimbayev, was taken into police custody for two months. The ongoing investigation pertains to Article 99 of the Criminal Code, which deals with "murder." The incident leading to his arrest occurred on November 11 when he allegedly beat his wife, Saltanat Nukenova, to death at a restaurant in Astana owned by his close relatives. Kuandyk Bishimbayev, who had previously held high-ranking positions in the country's leadership, had a prior criminal record. In March 2018, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison for accepting bribes but was later pardoned by former President Nursultan Nazarbayev in February 2019, subsequently being released on parole in October of the same year. (Vlast, 2023)

Fig.5 Death - Saltanat: Collage with notes by the author (2023). Photographs featured (left to right/top to bottom): Photograph of the victim and collage with detained alleged murderer from the Press.kz news outlet (2023); Marriage and crime scene photographs from the Akipress news outlet (2023).

Media reports indicated that restaurant staff were forbidden from calling an ambulance, and the ex-minister himself requested his cousin to urgently bring blankets and drive Saltanat Nukenova's cell phone around the city. Instructions were also given to delete the video footage from all surveillance cameras under the pretext of technical failure. (DW, 2023) In an effort to bring attention to injustices and corruption, women came forward, prompting a cascade of events that continue to unfold. The case received significant media coverage, and young Kazakhstani women initiated a flash mob called "Tired of Tolerating." (Weiskopf, 2023) They presented themselves as victims of domestic violence and called for the country's leadership to introduce criminal penalties for such offenses. Activists also highlighted several high-profile cases of violence against women and children that were reported in different regions of Kazakhstan in 2023.

While the history of feminist protests in independent Kazakhstan is relatively short, the public sphere has seen a notable surge in civil activism in recent years. According to masa.media, an independent news outlet, this timeline began with the Women's March in Almaty in 2017. This groundbreaking event in recent history, organized by the feminist group KazFem, brought together approximately 30 participants. Significantly, it was held without the official permission of the state (recieved in äkimat). (masa.media, 2023).

In 2019, another significant gathering occurred at the Sary-Arka cinema square, organized by KazFem participants with the support of NeMolchi ("Don't be silent") and FemPoint. This time, activists submitted 36 applications to the Almaty Akimat and other city councils to obtain authorization for their peaceful assembly. In response, some women faced threats of expulsion from universities if they didn't withdraw their applications, and the event was not officially approved by the state. During the gathering, four masked men approached, criticizing it as "inciting further conflict between the sexes." (masa.media, 2023) Nevertheless, the peaceful rally drew around 100 participants and addressed critical issues such as sexualized and domestic violence and the situation of women in correctional facilities and sex work.

In 2020, the application for a feminist rally was rejected by the akimat, but the march proceeded anyway. The number of organizing groups expanded, with support from activists associated with Feminites, KazFem, FemAgora, FemSreda, and SVET PF. The rally's demanded focused on the urgency of criminalizing sexual harassment and violence. More than a hundred participants marched from TSUM Trade Center to the Abay Theater of Opera and Ballet (GATOB), chanting slogans such as "My body is my business," "For women's freedom," and "Choose yourself," among others. (masa.media, 2023) Near the theater, activists symbolically burned a wreath in memory of victims of domestic and sexual violence. Later, the state issued an order to charge two march organizers, Arina Osinovskaya and Fariza Ospan, with a fee for petty hooliganism related to their participation in the public action and the wreath burning.(masa.media, 2023)

In 2021, the feminist march was coordinated with the state and took place on March 8th – International Women's Day. It became the largest peaceful gathering of women, with around seven hundred participants. The march, held under the slogan "Every Woman Matters," commenced at the Mahatma Gandhi monument and proceeded to the Academy of Science. Participants called for the consolidation of women's rights, the enactment of the Domestic Violence Act with stricter penalties, the eradication of gender inequality, and the release of women imprisoned for political reasons.

After the successful reception of the 2021 march, the city council 2022 decided not to coordinate the feminist march, citing an excuse that was later proven to be false. Nevertheless, the rally took place, attracting approximately five hundred participants, and focused on women's participation in politics. The event began with a minute of silence to honor the victims of the January events – a civil uprising brutally suppressed by the state in January 2022, resulting in over 200 deaths.

With the annual event's growth and the inclusion of other political agendas affecting women's lives and roles, such as the January events and the full-blown war in Ukraine, police officers were deployed throughout the assembly's perimeter, and police vehicles were stationed nearby. The rally incorporated many Ukrainian symbols and voiced strong condemnations of Russia's military invasion of Ukraine.

In 2023, the rally once again took place, attracting a substantial number of participants who came not only to support women's rights but also to stand in solidarity with the victims of the January events and against Russia's military aggression in Ukraine.

*An "äkimat" in Kazakhstan is an administrative structure led by an "äkim," who serves as the head of an "äkimdik"—a municipal, district, or provincial government. This role also involves acting as the Presidential representative. The President, with the Prime Minister's advice, appoints äkims for provinces and cities. Meanwhile, äkims for other administrative units are chosen according to the President's specified order. The President holds the authority to dismiss äkims. The powers of äkims conclude with the induction of a newly-elected President, and until the appointment of a new äkim by the President, the outgoing äkim continues their duties. An äkim heads an "akimiat," representing a state regional administration.*

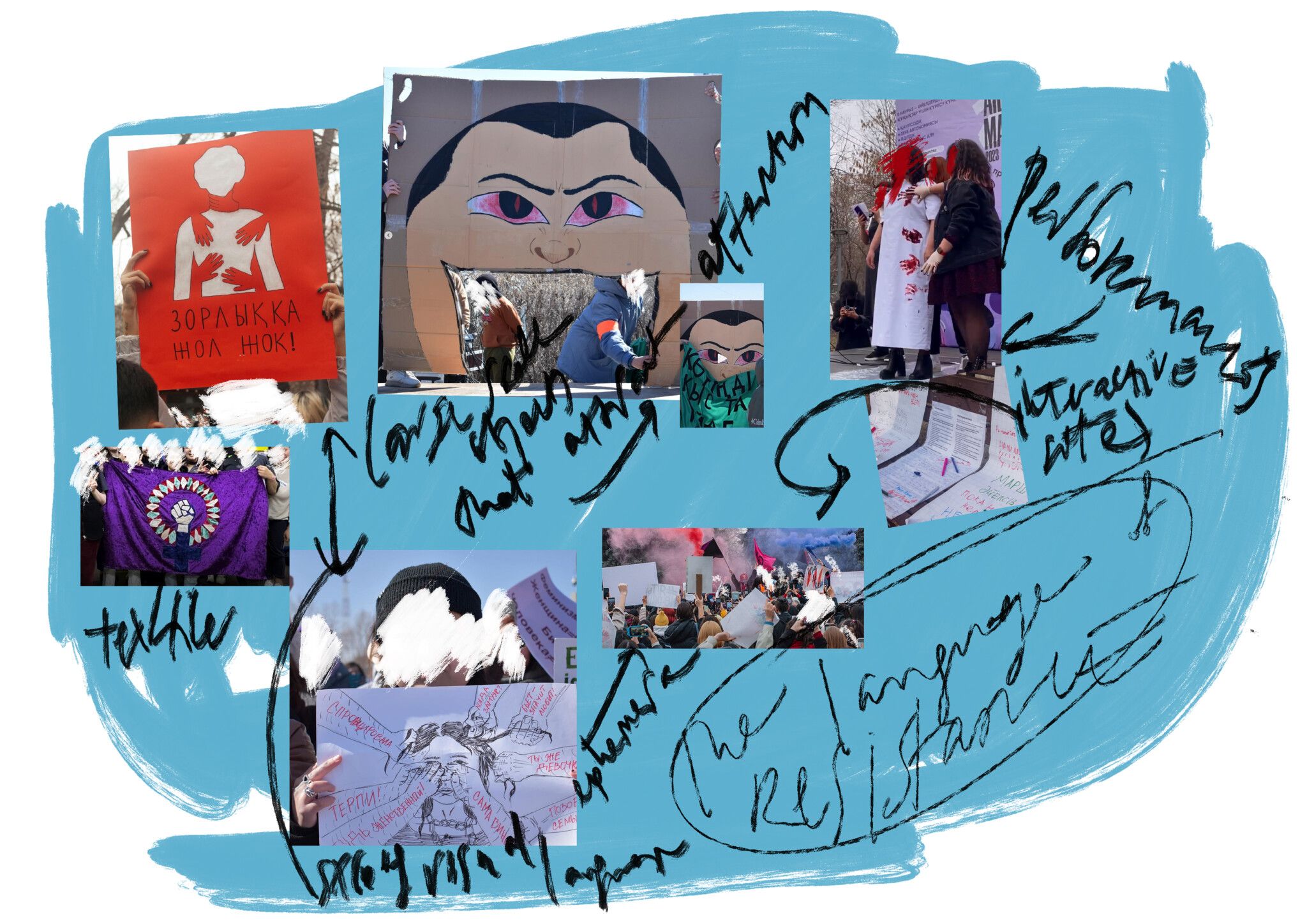

Fig.6 Feminist Marches in Kazakhstan - Feminist marches in Kazakhstan in recent years. Images sourced from public accounts of KazFem, Feminita.kz and from the personal blog of the activist Fariza Ospan. Collage with notes by the author (2023)

While it may be inappropriate to draw a direct comparison with the vibrant and carnivalesque formal strategies that underpinned Brazilian theater movements like Augusto Boal's Theater of the Oppressed, the emergence of recent protest culture in Kazakhstan shows clear signs of the resistance and solidarity project growing with resistance aesthetics embedded in the performative aspects of socially-engaged artists' practices and social movements.

For example, the feminist march in Almaty in 2017 featured a female mannequin erected as a monument to victims of domestic violence, while a six-meter banner boldly declared, "Freedom, sisterhood, feminism," according to Veronika Fonova of KazFem. In 2022, the march featured a cardboard coffin bearing the number 67, symbolizing the women who tragically lost their lives due to domestic violence in Kazakhstan in 2021. The event culminated in a flash mob, where participants formed a peace sign with their bodies and released colored smoke bombs, all accompanied by the slogan "No to war." (masa.media, 2023)

Evidently, as civil participation in feminist marches continues to develop, and organizers persist in bringing this pressing issue to the attention of the broader public as a political statement, activists are adopting a language of strong aesthetic antagonism. The inclusion of six-meter inscriptions and creative props in recent feminist marches reflects a diversified and innovative approach within the realm of political activism in Kazakhstan, utilizing aesthetics of resistance and solidarity that communicate through various formal languages.

Fig.7 The Language of Resistance and Solidarity - Images sourced from public social media of 8marchkzm, feminita.kz, the personal blog of Fariza Ospan.Collage with notes by the author (2023)

One of the works displayed as part of feminist marches showed the activists' performance. One of the women—dressed in white clothing—was touched by numerous people with a blood-red hand, leaving her body in blood-red clothing. The contrast of color and the vividness of action undoubtedly left an imprint on the audience and passersby of the event, especially considering the relatively conservative nature of Kazakh society.

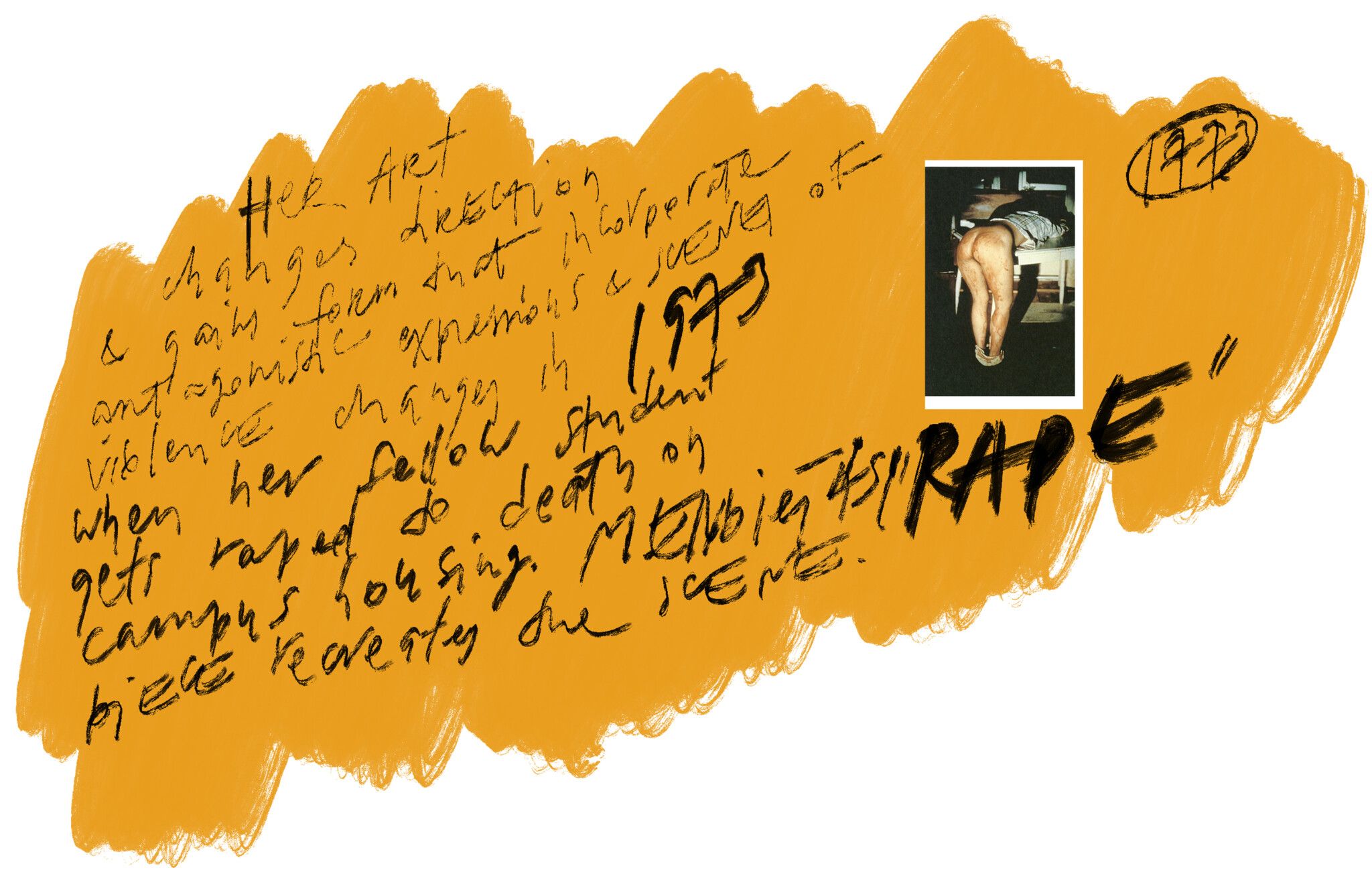

Ana Medieta’s work, often filled with exposed antagonistic and violent elements, was, too, prompted by an incident of rape that happened to one of her fellow students, Sarah Ann Ottens, on her campus in America in 1973. The “Rape Piece” where, shortly after the incident, Ana invited friends and mentors over, and when they approached her flat, they discovered the door open and found her unclothed from the waist down with blood trickling down her back onto the floor. As Sarah Ann Ottens, she was bound to a table with her hands tied. (Rosenberg-Klainberg, nd)The performance became her first piece to unfold a seminal theme in her work – dealings with blood and violence, while also exploring the interplay between female invisibility and femininity as a notion of natural divinity through recreations of indigenous deities.

Fig. 8 - The image of an artwork from Sofia Rosenberg-Klainberg's piece for Columbia LAIC “Ana Mendieta - Asian Diasporic Aesthetic Practice." Collage with notes by the author (2023)

Strong antagonistic language to target public attention at the most painful aspects of the social life of women, indeed, serves the purpose of demonstrating the necessity of dealing with the issue of violence because, in many cases, this is truly a question of life and death.

The growing urgency of attracting attention to the matters of domestic violence and the oppression of women’s bodies is demonstrated by the alarming statistics reported by numerous international organizations, including the World Health Organization. It clearly underscores that sexual violence, including rape, is a significant public health issue and a gross violation of women's human rights. This problem persists on a global scale and demands immediate attention. According to WHO's 2023 report, "Most of this violence is intimate partner violence. Worldwide, almost one third (27%) of women aged 15-49 years who have been in a relationship report that they have experienced some form of physical and/or sexual violence from their intimate partner." (WHO, 2023) The report emphasizes that violence against women is preventable, and it highlights the crucial role that the health sector can play. The report underscores the importance of institutional support for victims and the urgent need for resources to be allocated to investigate and prosecute perpetrators.

Fig.9 Rape Statistics - Worldwide statistics of rape by World Population Review (2023). The interactive map allows us to hoover over the country and explore its rates of rape. Use the link to view the interactive map: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/rape-statistics-by-country

As part of the World Population Review's ranking of countries based on rape statistics, it may come as a surprise to readers that Sweden is included in the top five countries. (World Population Review, 2023) The article highlights one of the significant challenges in obtaining accurate statistical data, particularly when it comes to rape statistics, which are notoriously difficult to collect. The primary obstacle stems from the fact that most victims of sexual violence choose not to report it. Various reasons contribute to this decision, including feelings of embarrassment, concerns about victim shaming, fear of reprisal from the perpetrator, and even apprehension about how their own families will react.

The inclusion of Sweden in the top five countries in rape statistics, initially surprising, offers a glimmer of hope. Sweden's high reported numbers may actually indicate positive changes in rape prevention efforts. These statistics do not always provide the full picture. Increased reporting can result from factors such as a broader definition of rape, improved tracking of previously unreported cases, enhanced legal measures against rapists, or better support for victims, encouraging them to come forward. In other words, women may feel safer reporting abuse, and the state takes action to address the situation, investigate cases, and thus, prevent potential future incidents.

The role of trustworthy institutions in the lives of women and all citizens is crucial for the development of any society committed to improving the well-being of its people. However, in Kazakhstan, institutional bodies have repeatedly demonstrated that expressing public opinions, particularly in an impactful and attention-grabbing manner, can lead to dire consequences. In the context of Kazakhstan, a country with traditional values and predominantly conservative views, gathering such statistics remains an exceedingly challenging task. Notably, the repeated arrests of prominent female activists in Kazakhstan, whose cases have garnered significant public attention, illustrated that the institutional memory in Kazakhstan remains strong and can display its most punitive side when deemed necessary.

Institutional Memory: Reversed Roles

These reflections and loose associations were penned as I attended Ana Mendieta's exhibition. I was surrounded by projections of a woman's body expressed in acts of burning, drowning, floating, and adornment with blood, leaving traces of her existence on the land, trees, and sand. Inside the space, the sound of dripping water within free-form pools on the floor's surface served as a soundtrack to my thoughts.

Fig. 10 Energy Charge - Images from the show: “Energy Charge,” 1975, 16mm film transferred to high-definition digital media, color, silent, 49 seconds; "Alma, Silueta en Fuego" (trans. "Soul, Silhouette on Fire") 1975 Super-8 color, silent film transferred to DVD; 3:07 min. All images are copyrighted by The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong. Photographs taken at the show by the author (2023)

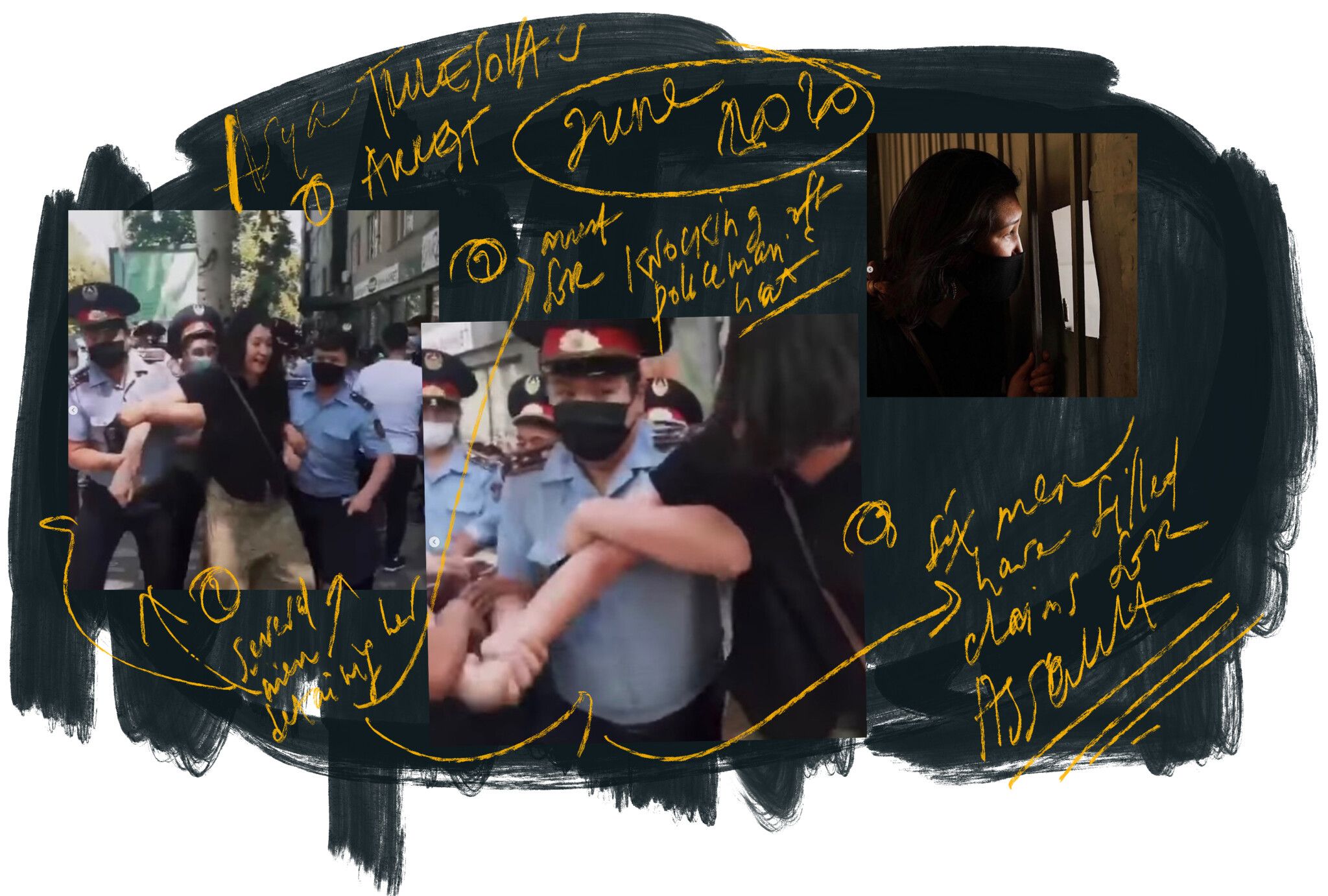

I diligently recorded my impressions in a notebook that had journeyed with me from Berlin. Amidst these thoughts and connections, memories of a time when my mind was consumed by concern for my friend, who was unjustly accused of "abusing" six adult policemen in Almaty during the summer of 2020, prevented me from fully immersing myself in the exhibition.

At that moment, I felt a profound need to express my gratitude to the artist: "Thank you for evoking these emotions; thank you for sharing the most sacred aspect of your being—your body and your artistic expression—with me, a woman from Kazakhstan. Your art compels me to reflect on instances when the bodies of my fellow women were confined and in desperate need of help. Ana, you may not have known how similar the stories of women in Kazakhstan are to those in Cuba, America, Mexico (the places you lived), and Brazil, where we encounter your art. We are all united in this vessel of resistance and solidarity. Each and every one of us—women and children."

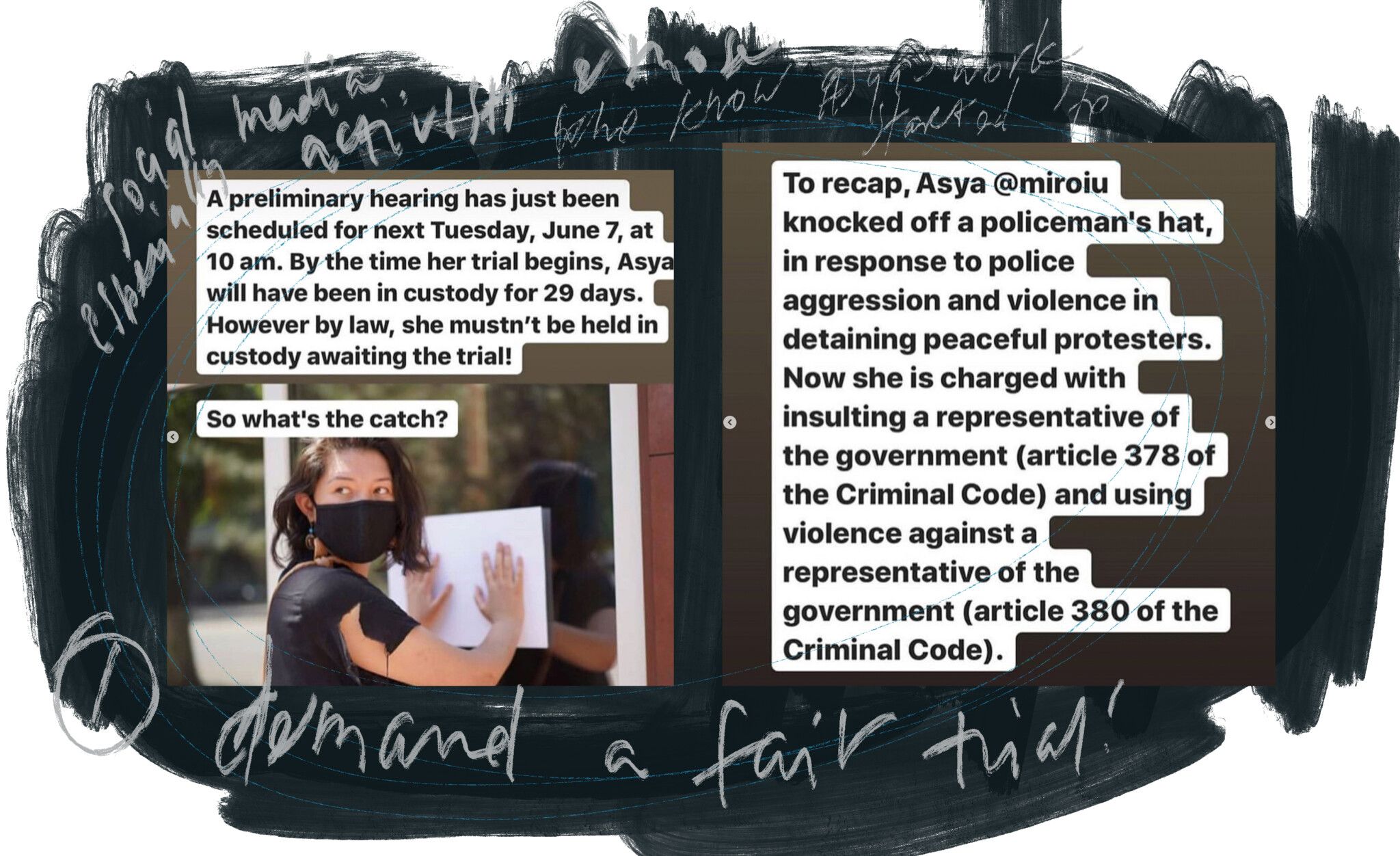

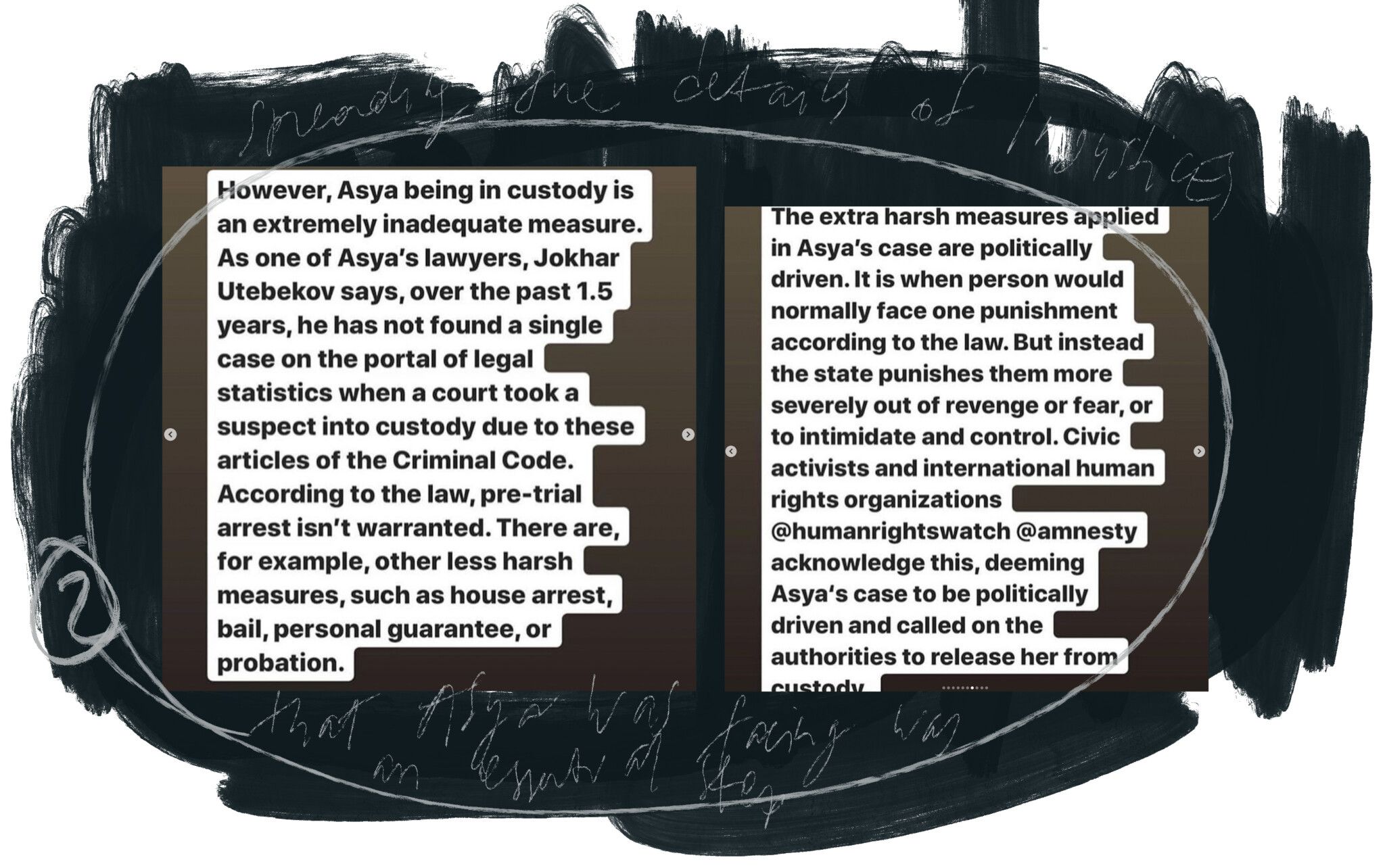

I vividly recall that it was early June 2020, and the COVID-19 pandemic had just begun. People were adjusting to the new "normal" of wearing masks and practicing social distancing, as top-down lockdown orders were issued. During this time, I was in the midst of preparing an artist-in-residency application for the open call titled "Does the Blue Sky Lie?" Just a day prior, my friend and female activist, Asya Tulesova, had been arrested at a peaceful protest in Kazakhstan, where she had courageously defended elderly individuals who were being mistreated by the police.

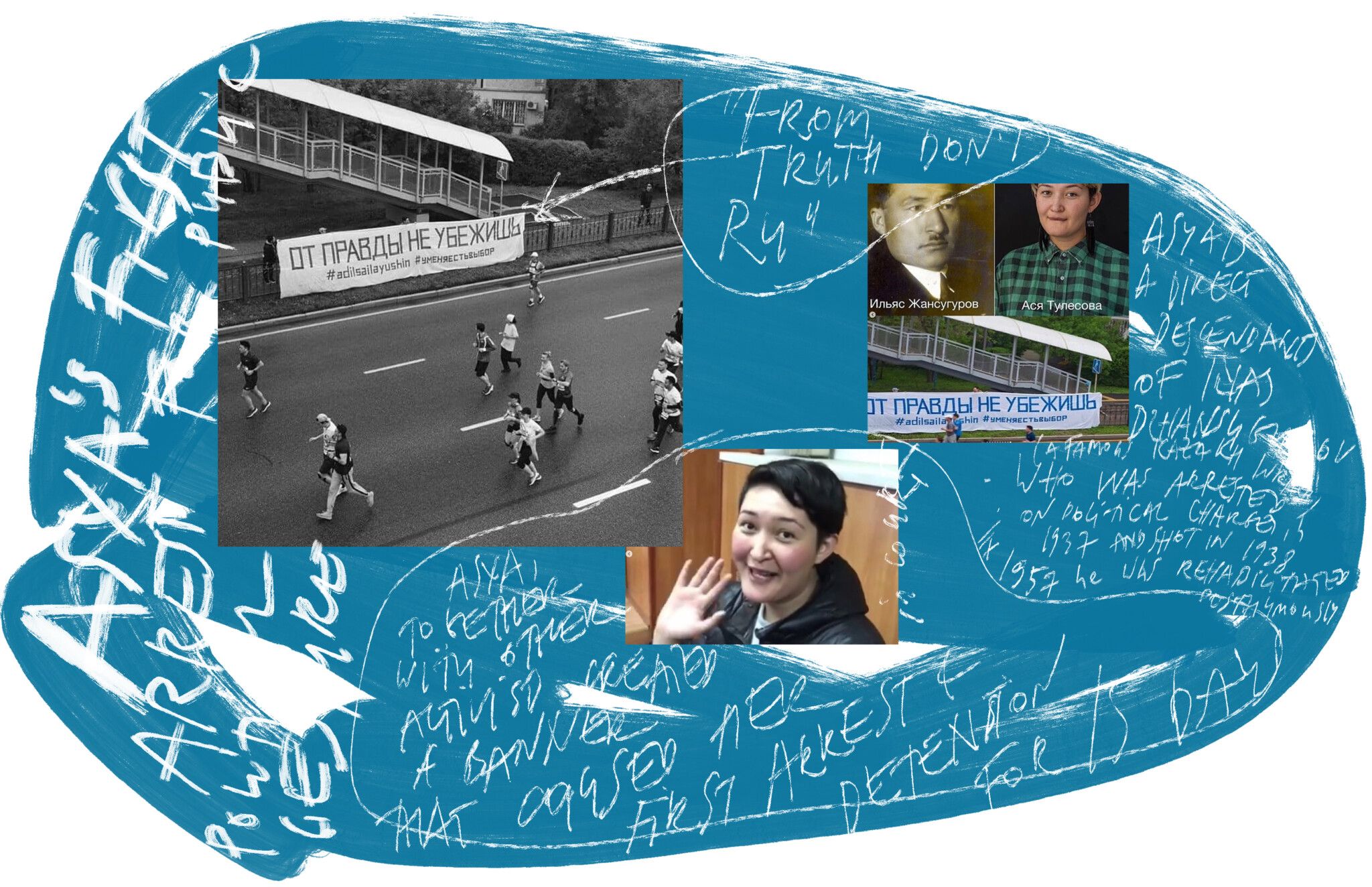

Fig. 11. Asya Tulesova’s arrest - Images are sourced from the social media accounts that were featured as evidence during the trial of Asya Tulesova; the image of Asya detained is sourced from public accounts of activists in Kazakhstan. Collaged by the author (2023)

Asya found herself in the grip of several policemen, and in the process, she inadvertently knocked the hat off one of them as she was forcibly led to a police vehicle (autozak). The incident was captured on camera and widely shared on social media, sparking a surge of online and on-site social-political activism. Meanwhile, Asya was detained for several months and subjected to a trial for "assaulting state representatives." This female activist, who had merely sought to assist elderly individuals during a peaceful protest, was accused of assaulting not one, but six police officers who claimed to have felt threatened by her, leading to charges of both physical and moral assault.

After that, to put the stories and contributions together, participants were invited to collectively imagine the future of coliving within each of the categories and create a shared piece through lino-carving. In an unexpected parallel to many real living situations, the pieces of linoleum that we cut into many funny-shaped pieces, initially intending them to come back together into a neat rectangle, refused to form into such an orderly structure. Instead, the final lino-tapestry ended up taking a shape that none of us had planned or had full control over, making sense only as something collectively decided.

Through this shared visual imagination we hoped to create a starting point for new resistance in our everyday coliving realities.

Let's contemplate the reverse scenario within the confines of a reductionist perspective and contextualized in the rather traditional, conservative society of Kazakhstan. How many of those women who reported instances of sexual abuse or domestic violence ever made it to a trial? None, to the best of my recollection. At least none of the public cases that women of Kazakhstan could remember to have been so visible and public.

So, it was June 2020, and we were deliberating whether to apply for a residency titled "Does the Blue Sky Lie?" For those unfamiliar, blue is the color of our national flag, symbolizing the peaceful and clear skies that stretch over the residents of Kazakhstan. It is also the color of the document that defines our citizenship. "What a beautiful passport," is a phrase that perhaps every Kazakhstani has heard during airport encounters. An artist, Anatoliy O, so brilliantly spoke about this relationship between citizenship and a homeland and the contradictions of the peaceful blue sky it promises to its people. The ornamentation on our passports and their distinctive blue hue are unforgettable. However, the system they represent, for various reasons, leaves a lasting impression as well.

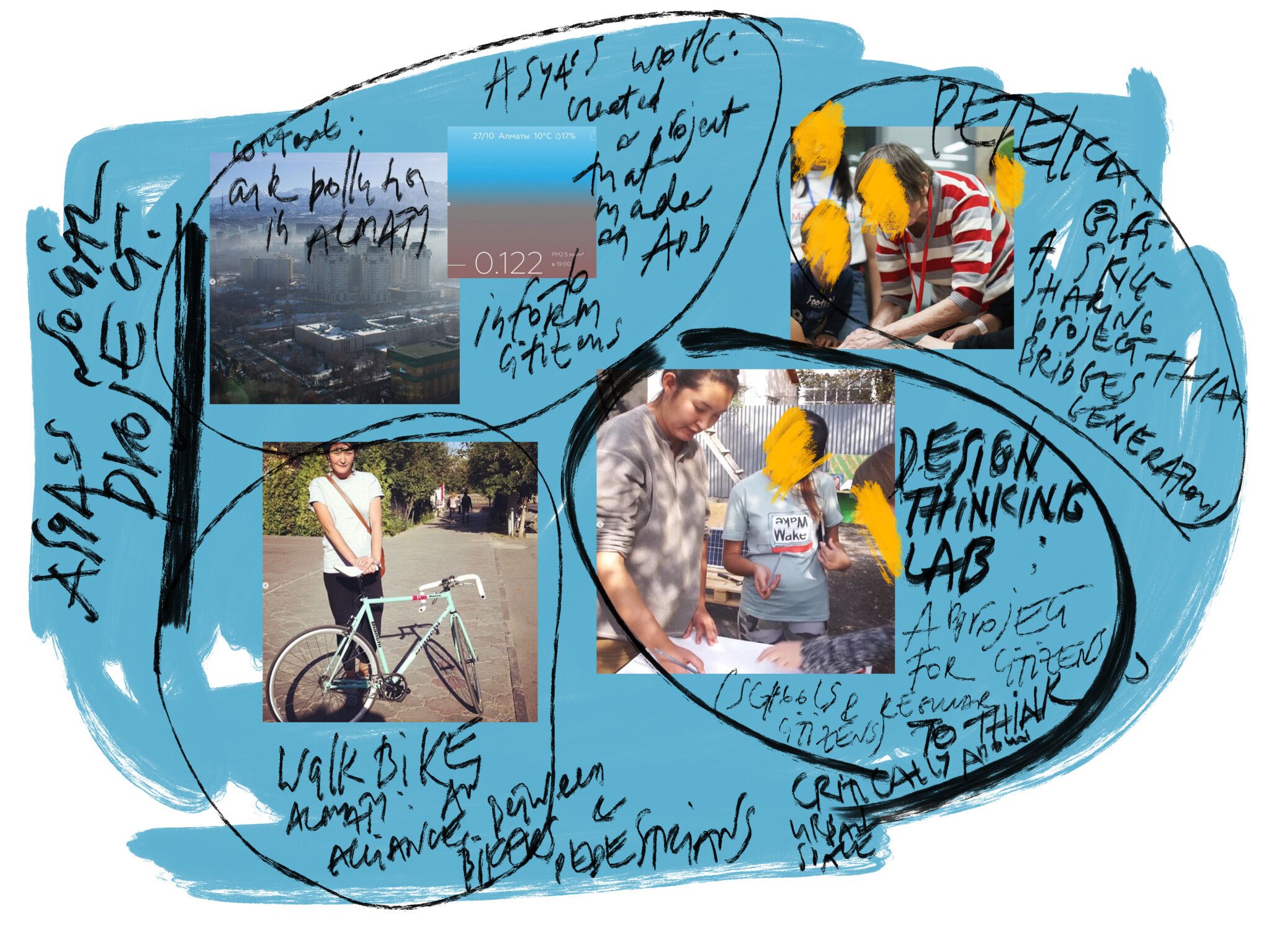

Like many countries burdened with the label of "developing," Kazakhstan's power structure and justice system are intrinsically corrupt, and the need for reforms has long been apparent. Even the sky itself no longer appears as blue as it once did. Years of industrial pollution, a lack of proactive measures, insufficient education on the subject, and a dearth of cooperation from major stakeholders have resulted in a perpetual smog lingering over the city that endangers the health of the citizens. (Tyo and Gu, 2022) Everyone recognizes that political changes are imperative, yet many choose to remain silent out of fear, while some, like me, seek personal and professional paths outside of the country. Nonetheless, a brave few, like Asya, opt to stay and take action.

Asya was among those young activists who dared to address these issues and endeavor to implement solutions. We watched as she methodically attempted to collaborate peacefully with the system, striving to gradually address the accumulated problems. Each time, the system managed to thwart her efforts, undaunted, Asya rallied a group of friends and supporters and, together, they launched educational and environmentally focused projects like AUA which soon gained visibility among the wider public. (Shatayeva, 2017) They developed an app to measure pollution levels and acquired various measuring devices. Eventually, they succeeded in forging alliances with those in power, who initially resisted their project. Her patience and non-confrontational approach triumphed.

Fig. 13 Asya’s Social Work - Images are sourced from the social media accounts / public accounts of activists in Kazakhstan. Images were featured and shared as part of the campaign to raise awareness about Asya’s case. Collaged by the author (2023)

To name a few of Asya's other projects: the BikeWalk Alliance, Petelka.gift (a project that assisted elderly individuals, often living on the brink of poverty in Kazakhstan, in selling their handmade items and conducting workshops), and the Design Thinking Lab (a project for schoolchildren that encouraged critical thinking about their environment and proposed constructive actions, such as building benches, installing trash bins, or planting trees, to address perceived deficiencies).

Within the context of changes in 2019, when after holding power for 28 years, Kazakhstan's former president stepped down and appointed a new leader, the political energy of the city was highly charged with uncertainty and hope. Deprived of fair elections since the collapse of the Soviet Union, many saw this event as the first opportunity for genuinely democratic elections in the country. Asya, being herself, took this notion further than mere contemplation and peacefully unfurled a banner that read "From Truth Don't Run." (Adamdar 2020) For this act, she received a 15-day prison sentence—an outcome that should leave many pondering its rationale. The poster was meant to motivate citizens to exercise their right to vote. However, in the eyes of those in power, such motivations were less desirable.

Fig. 14 Asya’s First Arrest - Images are sourced from the social media accounts / public accounts of activists in Kazakhstan. Images were featured and shared as part of the campaign to raise awareness about Asya’s case(s) – here, her first arrest for public political action. Collaged by the author (2023)

In 2020, when more than a year had passed since that incident, protests continued while those in authority remained largely unchanged. The system remained persistently broken and in need of repair and people became more active both in the streets and in social media. During this time, Asya and other activists tirelessly worked to educate people about their rights, how to engage in peaceful protests, how to interact with the police, and how to navigate the judicial process. Over the past years, many activists were sentenced and imprisoned without a fair trial, with the coronavirus pandemic exacerbating the issue as trials were conducted behind closed doors.

As a result of Asya’s being active in defending elderly citizens who attended peaceful protests, throughout the whole summer Asya has been held in captivity, awaiting and then attending the trial for sweeping a police officer's hat with a hand during a protest—an emotional response provoked by police officers abusing their authority and resorting to violence against peaceful protesters and unfortunate bystanders, including the elderly. (Human Rights Watch 2020)

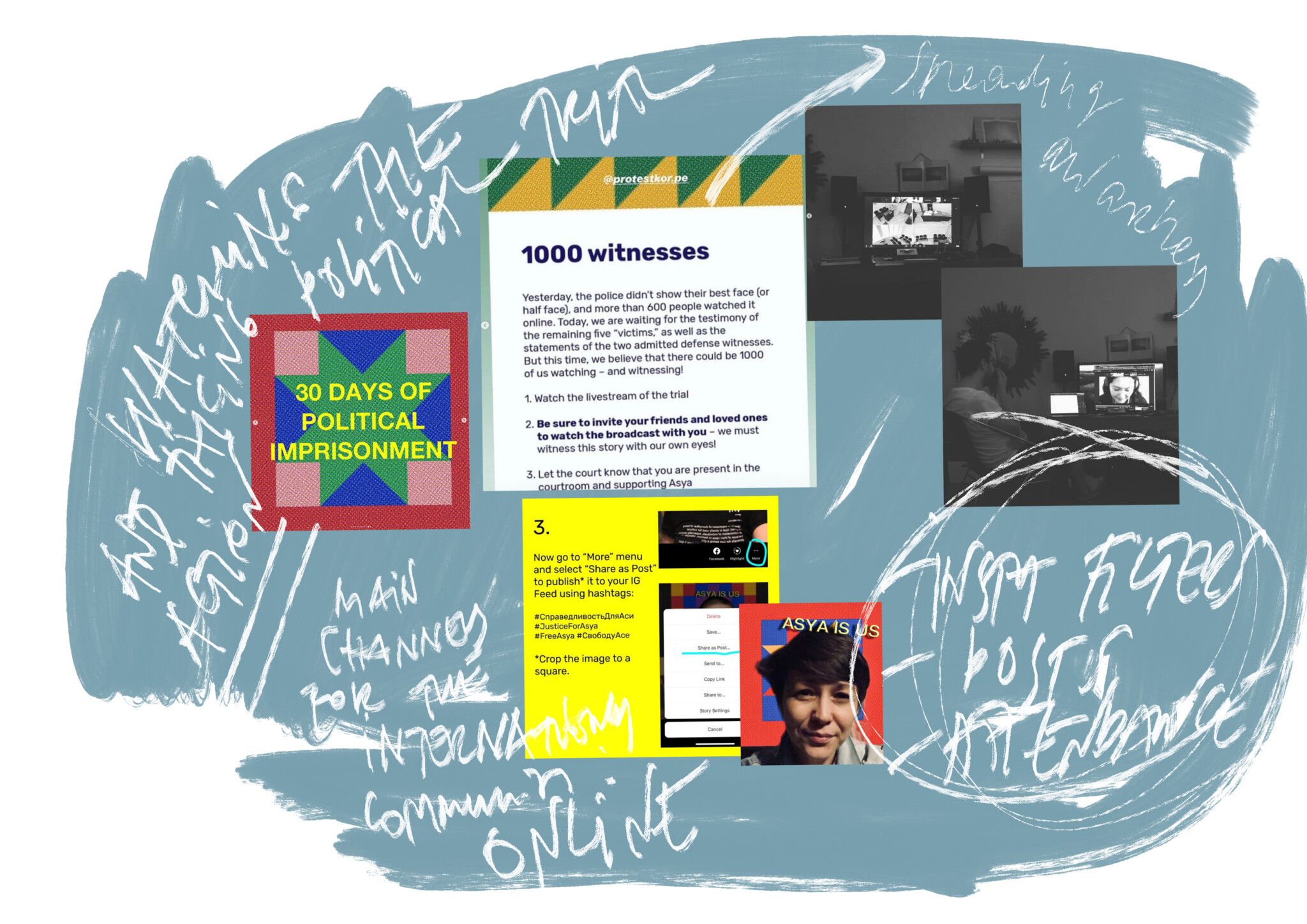

Fig.15 From Asya's hearing (documented from snapshots of an online legal procedure) Images of the trial during the summer of 2020 when Asya was detained for knocking off the hat of the policeman. The recordings of online streams (public court sessions) are documented by the political party Oyan Kazakhstan and can be viewed on their YouTube channel. Collaged by the author (2023)

The fact that Asya stood at the center of attention and faced the prospect of up to three years of imprisonment without a fair trial was tremendously troubling. However, it also demonstrated an opportunity to demand change. Seeing the lack of education, professionalism, and diligence among the representatives of the state that became evident during the online trial, people became weary of the indifference and unresponsiveness of those in power toward justice and legal procedures.

With numerous social media posts and gatherings, Kazakhstani people all around the world stood in solidarity with those calling for a fair trial for Asya and other activists. People also shared the message in English because they wanted the world to be aware of this case, and many international friends and followers of the political situation in Kazakhstan also witnessed the online trial. (Adamdar 2020) The precedent was not only a manifestation of police violence in an authoritarian regime but also an act of violence against women in a reversed situation of power system, as well as in the case when anyone who risked their life to help others in the hope that one day we would have clear blue skies overhead. Ironically, Asya Tulesova's great-grandfather, a resident of Soviet Kazakhstan and an active citizen and cultural activist, was imprisoned and killed as a result of false accusations during the Stalinist political regime. (Alimtayeva 2018)

"They say that history repeats itself, yet sometimes there are people like Asya who see a way out of the cycle, and we need to trust these individuals and navigate the course of change together. We stood in solidarity with Asya's supporters and demanded a fair trial for her!"—this was the message the2vvo posted on social media in June 2020. Instead of applying for a residency, we joined the social movement to raise awareness about Asya's case and her impending trial.

One of the viral works on social media that defined the feelings of people in Kazakhstan who have been witnessing the summer events of 2020 was Anatoliy O.'s piece “What Color Is Your Passport?” The work echoes many of those who carry Kazakhstan's tranquil blue passport both at home and abroad.

*Post from Social Media (published on Instagram on June 7, 2020) "The following fragments are from Asya's live stream on Instagram, recorded on June 5, just moments before her arrest. The first video fragment is shot about a hundred meters away from where the police are forcefully loading protesters and bystanders into police vehicles without following proper procedures and with great violence. The second fragment shows Asya being grabbed by the police. She manages to escape their grasp but remains with the protesters. In the last video, shot in darkness, Asya hides her phone, and we can only hear the sounds of people in agony. The cries of pain are heartbreaking, and it's truly shocking to witness the inhumane behavior of the police in Kazakhstan. The video leaves no doubt about the brutality of the violence. An elderly man can be heard crying out, "My leg! You are breaking my leg!" In the background, a woman's voice joins the chorus of distress. The video concludes with Asya inside a police car, where she continues to try and comfort the people who were apprehended alongside her. The full video can be watched on Asya's Instagram TV live stream from June 5, 2020, available on her account @mirou. We fervently demand a fair trial for Asya and all the other protesters!" - @the2vvo*

With the tremendous efforts of initiatives like Protest.körpe, as well as the dedication of other activists, artists, and cultural workers in raising awareness about Asya's trial, progress was made. These efforts materialized in various forms of expression: written manifestos and social media posts, public gatherings, collective viewing of trial sessions that lasted for months, posters, textile works, digital filters for social media, poetry, and performative works. The scope of public resonance, both in digital and physical formats, was vast and set a precedent for a civil action that garnered attention and initiated change, even if on a modest scale. The collective work of many individuals bore fruit.

*Körpe, in Kazakhstan, holds significance as a traditional household item in Kazakh society. Essentially, it is a blanket or quilt with historical roots in the use of stallion skin, later processed and bordered with fabric. Various types of körpe exist, including those crafted from specific fabrics and filled with down, cotton, or wool. Woolen (camel) körpees are highly regarded for their warmth, durability, and value. Covers made of silk, satin, or other materials are often chosen for their aesthetic appeal, and to enhance durability, körpees are quilted with diverse patterns. Patchwork körpe, referred to as "kurak" in Kazakh, is skillfully sewn from geometric fabric patches, resulting in a diverse array of patterns.*

Towards the end of summer, Asya was pronounced guilty and received a 1.5-year probation, that is, not being able to leave Kazakhstan with an obligation to sign off regularly. While the “guilty” verdict was devastating news, within the context of Kazakhstani politics and the prosecution system for political prisoners, with all its dreadful "arms," the fact that Asya was at home and safe felt like a small victory.

It is worth noting that Asya Tulesova's case—a woman popular among her contemporaries, eager to engage in the political arena, interested in improving the lives of vulnerable social strata, and focused on environmental issues—has been a lesson learned the hard way. The institutional memory, with Asya being found guilty of a crime she never admitted to, according to the country's laws, will likely prevent her from entering the political arena in a capacity that could have benefited the people of Kazakhstan and could have been possible if the state was receptive to change.

Fig.17 Asya Released. On August 12, Medeu District Court No. 2 in Almaty released Asya Tulesova while still finding her guilty and sentencing her to a fine of ~$130 under Article 378, section 1. As a sentence, Asya received one year and six months of probation under Article 380, section 2. After sentencing, Asya Tulesova was released from pre-trial detention, where she had been held for more than two months. Image sourced from adamdar.ca. Collage and notes by the author (2023).

We are as old and wise as the land

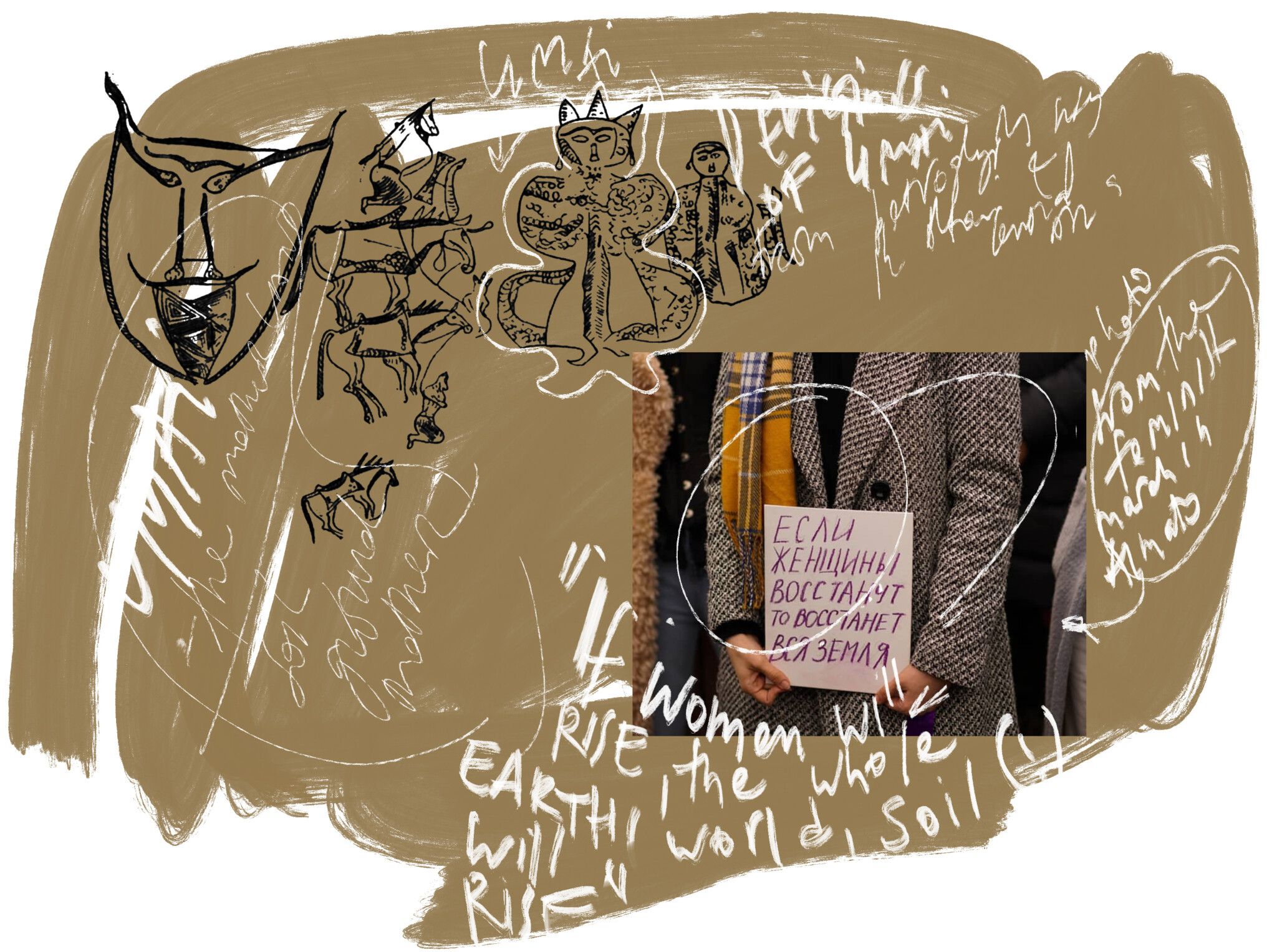

After spending over an hour in the first part of Ana Mendieta's exhibition, I moved on to the works that no longer bore the artist's bodily imprint but instead featured female figures cut out of cliffs and crafted from soil and sand. As I observed these figures drawn and imprinted on the earthly medium, I couldn't help but draw a connection between Mendieta's work and that of other artists worldwide who link the female body with the symbolism of the earth, deeply rooted in the connectedness of people with the land. The grounding and nurturing capacity of the earth, which holds us firmly through the force of gravity, allows everything to simply exist. It's almost as if Erich Fromm's concept of unconditional motherly love, without which one expects to encounter hardships of trust (Funk & Shaw 1982), materializes in the substance of the earth—enduring, supportive, nurturing, and sustaining. Regardless of anything else, the soil beneath our feet serves as a foundation for our bodies. Therefore, it's not surprising that in Central Asia and Altai, the revered deity representing the essence of female nature, known as Umai, was depicted in petroglyphs amidst scenes of funeral rites.

Fig.18 Soil - Mendieta’s work: "Volcán," 1979 Super-8mm film transferred to high-definition digital media, color, silent; "Untitled Old Mother Blood" ("Rupestrian Sculptures"), 1981, silent. All images are copyrighted by The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong. Photographs taken at the show by the author (2023)

In Turkic culture, the goddess Umai holds a significant place in the religious beliefs, mythology, and visual art of the Turkic-speaking peoples of Siberia and Central Asia. Umai, as the spouse of the god of Heaven Tengri, personified the feminine principle, served as the goddess of fertility, and watched over children. (Kairbekov 2012)

As seen in the petroglyphs from Kudyrge—a testament to the ancient world art of Sayano-Altai—the dignified and majestic posture of the entire figure, particularly the extraordinary three-horned headdress, does not merely signify the exceptional nobility or privileged status of this woman, but rather her divinity and endurance. Umai, without a doubt, is a female deity venerated by shamanists and the protector of children and fertility, but also a warrior. (Mukanov et al 2021)

Umai, at its core, symbolized the harmony of existence and all living organisms. The respect and reverence for Umai, represented by the soil, were passed down as wisdom from one generation of nomadic tribes to the next. Children were taught not to needlessly poke sticks into the soil or damage trees, as it was believed that doing so amounted to "violating" the very soil that sustained them. For nomads, the soil was the source of life, as tribes relied heavily on their cattle and followed the natural cycle of seasonal pastures. As the Kazakh proverb goes: "Zher - Anasy, Mal - Balasy," which translates to "The Earth is the mother nurse, and the cattle is the child of Earth." (Kairbekov 2012)

In Mendieta's depictions of females crafted from sand and soil, the shapes and forms defining the female body symbolize the nurturing nature of the environment. It's challenging to assign a specific date to these pieces, and their updated nature leaves them in a kind of temporal obscurity. Observers might wonder if they are gazing upon an archaeological site, a manifestation of land art, or the artistic expressions of a child attempting to depict their mother on the sandy slopes of a hill—a canvas concealing the intangible joys of play. The surface's fragility, as seen in the video, introduces the dimension of temporality and prompts the question of how much longer these imprints will remain visible. Tucked beneath the steep slope of the hill, viewers are left alone with the artworks, experiencing the excitement of discovering hidden treasures, as if they were ancient petroglyphs yet to be unearthed and revealed to the world.

Fig.19 Umai - Umai (Umay). Petroglyph on a stone from the Kudyrge burial, Altai, featured in Mukanov, Malik F., Gulfiya T. Meldesh, and Ayaulym M. Hurbekova. "The Image of the Goddess Umay in the Contemporary Fine Art Culture of Kazakhstan." Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) 13, no. 1 (2021):1. The image of the recent feminist march in Kazakhstan is sourced from public accounts of activists. Collage and notes by the author (2023)

The scale of these works is also challenging to grasp—curved body forms suggest a grander scale than the artworks actually possess, a perception that becomes evident upon closer examination, especially when compared to the bits of grass that one might initially overlook.

Indeed, the fragility of the human body, the confined nature of our temporal presence, and the enduring spirit of Umai, recognized by any Kazakhstani woman familiar with the deity, are all themes that resonate with and continue to be suppressed in Mendieta's series of works.

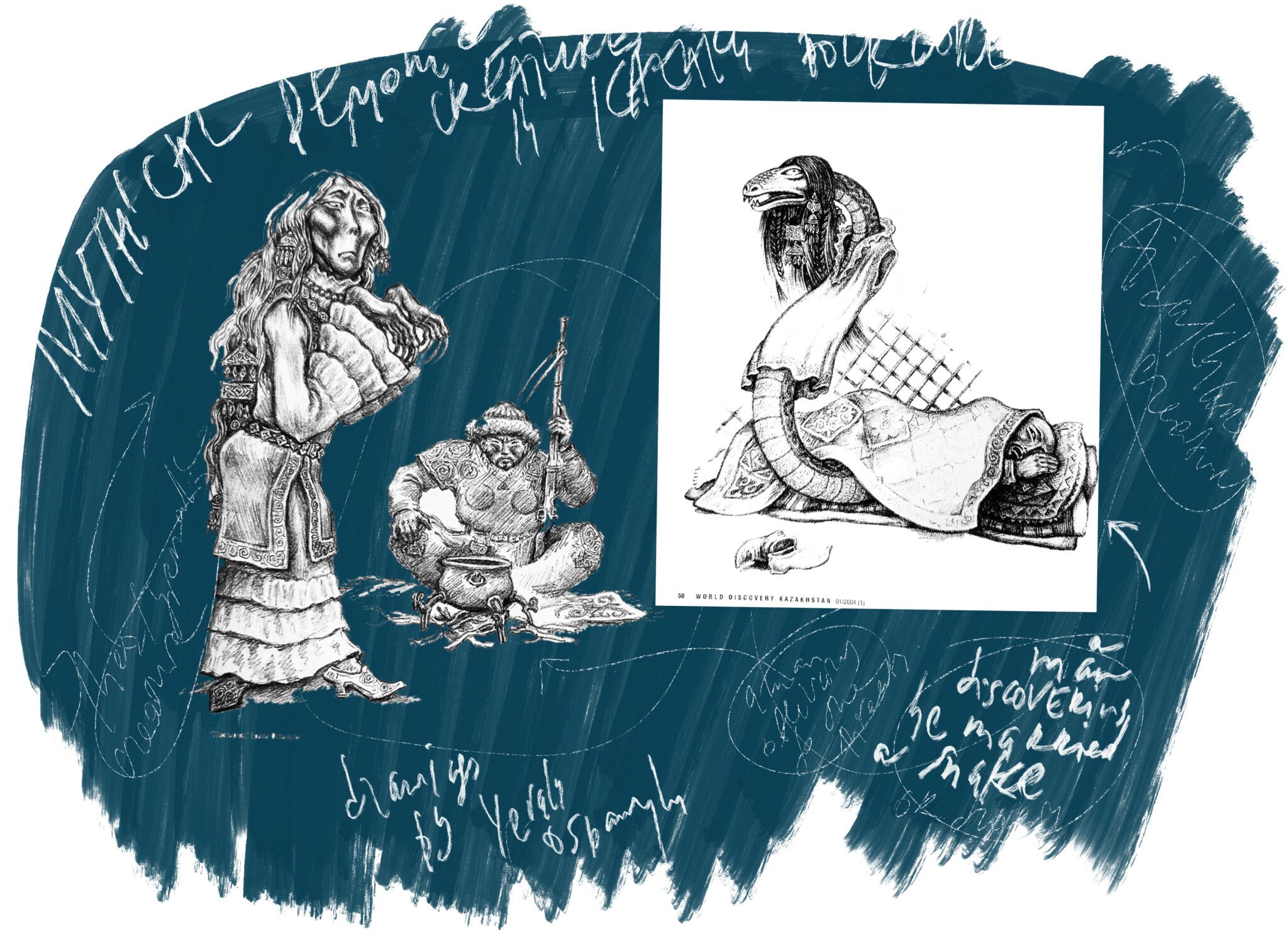

In addition to the goddess Umai, many ancient Turkic tales also depict women as demons, with one of the most common and widely varying appearances being that of Albasty. Albasty is a mythical demonological creature with origins dating back to the pre-Islamic period, often mentioned in Kazakh folklore. Albasty is typically depicted as a female creature with an unattractive appearance and saggy breasts. She is often seen in the form of a dog, a fox, or a goat, carrying a stolen human lung in her teeth. It is believed that Albasty is most dangerous in areas and circumstances involving childbirth, and the stolen lung belongs to those who do not survive the birthing process due to Albasty's enchantments. Encountering Albasty can lead to a person's death or deception. (Ospanuly 2004)

Kazakh folklore features several other female deities that represent various aspects of the portrayal of women. For instance, there is Zhestyrnak, a mythical creature that appears as a beautiful and humble woman seducing people. She wears clothing adorned with golden and silver attributes, and the sound of her attire signals her approach. Zhestyrnak speaks briefly and unilaterally, concealing her hands, which hide her long, oversized fingers. When her host falls asleep, she reveals her long fingers and nails, grabbing the victim and drinking their blood. There are also tales of Zhestyrnak's vindictiveness, and if she falls victim to her host and loses her life, her ghostly husband and ghostly children begin to follow the unfortunate people who encountered her on their path. (Ospanuly 2004)

Fig.20. Soil is Our Shared Motherland. Documented sketches of Ana Mendieta’s work in Cuba (1981). The series is titled "Esculturas Rupestres," translated as "Rupestrian Sculptures" (trans. Old Mother Blood). Collage and notes by the author (2023)

More illustrations of female demons are expressed in the images of Zhalmayuiz Kempir, an old woman who sucks blood from young women she encounters, draining their life energy, and Aidakhar, a dragon or snake that takes on the form of a woman and marries into a village (Aul). During the nights, Aidakhar consumes the residents of the village. (Ospanuly 2004)

These exemplary beliefs—Umai, contrasting with Albasty, Zhalmayuiz Kempir, and Aidakhar—do not fully represent the multifaceted cultural perspective on the role of women in Turkic cultures. However, they do hint at the existence of contradictions—a recognition of women's endurance, strength, and fertility, while also emphasizing the need for caution not to fall under the spell of women, not to give her power and not to deviate from established traditional roles. In these traditional roles, women often occupy secondary positions within the socio-political domain of society while bearing the primary responsibilities for domestic and service work in traditional households.

The complex power dynamics within both domestic and public domains, established by traditional power structures among nomadic communities, have evolved over time. Nevertheless, they have left lasting imprints that women in Kazakhstan continue to grapple with today. These challenges encompass various aspects, including redefining women's roles in public spaces, making choices regarding their appearance and personal decisions related to social reproduction and careers, active participation in the socio-political arena, asserting liberties for self-expression in diverse environments, advocating for the reevaluation of outdated traditions to align them with contemporary realities, and, most importantly, demanding the right to protection from abuse and violence that persists in domestic, public, and professional settings.

In today's climate, where longstanding and entrenched societal norms are being reevaluated, Kazakhstani women are taking to the streets to demand protection within their households.

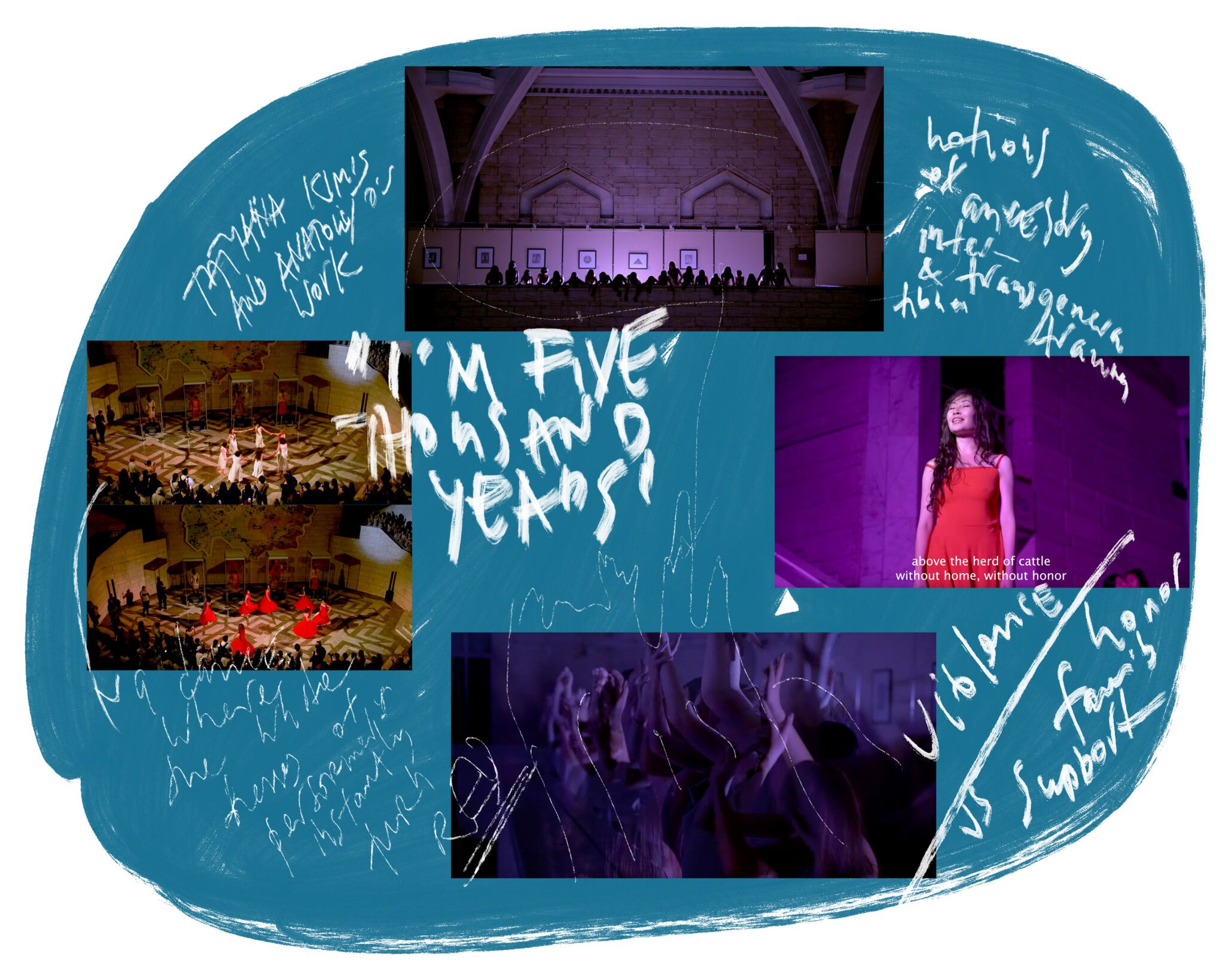

Director Tatyana Kim, originally from Kazakhstan and now based in Los Angeles, addresses several of these critical issues through her artistic work.

In her 2022 performance titled "I'm Five Thousand Years," held at the National Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan, she dedicated the immersive spectacle to the victims of domestic violence. The performance featured scenes that included striking oversized shadows cast by female performers, with various hands and body parts highlighted as distinct from their bodies, creating a sense of unity among them. A choir comprising twenty-one women contributed to the shamanic atmosphere and narrated the ancient tale of enduring oppression by power structures, the patriarchal gaze, and domestic violence.

Fig. 21 Myths - Yeraly Ospanuly's drawings were featured in World Discovery Kazakhstan (01/2004) (1), on p.50-53, demonstrating mythical and demonological creatures that are attributed with features associated with women. Images courtesy of World Discovery Kazakhstan publication. Collaged and annotated by the author (2023)

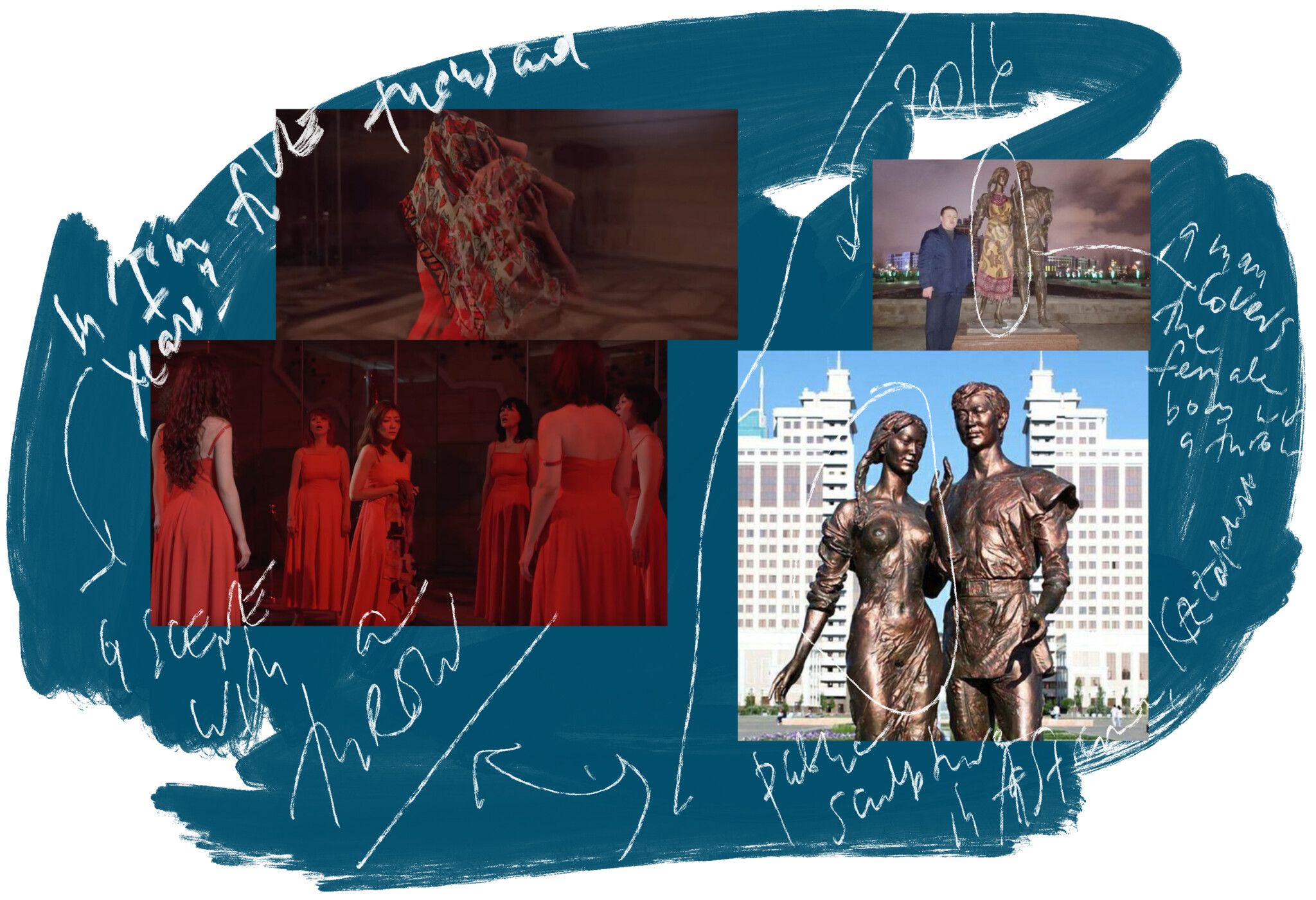

One episode in particular carries a resemblance with a scandalous case that received wide resonance among women of Kazakhstan in 2016. An Astana resident, Talgat Sholtaev, has covered expressive female parts of the public sculpture "Lovers" with a throw, intending to take measures against revealing women’s bodies in public, even as part of the artwork. In defense of his actions, the citizen claimed that he was “ashamed” of the work representing Kazakhstani women. (Tengri.news 2016) The notion of shame, in traditional societies is one of the main pillars that allows for oppression and power over other people’s bodies. In the Kazakh language, there is a term that stands for this notion, and that often refers to women’s behavior and attire. According to psychologist Aisulu Sailaukhanova, the Kazakh term "Uyat" extends beyond mere shame. It represents a profound aspect of the Kazakh cultural framework, encompassing age-old traditions, social ethics, communal perceptions of "good" and "bad," as well as anxieties and uncertainties transmitted through generations. "Uyat" serves as a summons from traditional society to conform, avoid standing out, refrain from venturing into the unfamiliar, and experience shame for one's thoughts and deeds that deviate from the majority's opinion. (Akmullaeva 2023)

Fig. 22 "I’m Five Thousand Years" – Tatyana Kim’s and Anatoliy O’s performance in Almaty, Kazakhstan, addresses the issues of domestic violence. Image courtesy of Tatyana Kim and Anatoliy O. Collaged and annotated by the author (2023)

In the "I'm Five Thousand Years" performance that features Kazakh women who know exactly how the social norms are carried in traditional societies through generations, Tatyana Kim and Anatolyi O demonstrate the confluence of many faces and voices of women’s ancestry. In her piece, they have experienced multiple incarnations, bearing the pain of their sisters through these lifetimes, repeatedly reborn to discover the inner fire and strength needed to cradle this universe in their gentle hands. “To my sisters around the world—in Kazakhstan, Iran, Afghanistan, and every corner of the globe—we witness your remarkable courage as you fight for justice, freedom, and a better future. May we collectively evolve into more just and harmonious societies worldwide. We stand by one another, coming full circle. In Kazakhstan, 400 women lose their lives to domestic abuse each year. 'I'm Five Thousand Years' is dedicated to these victims,"– the message that creators send out. (Kim 2023)

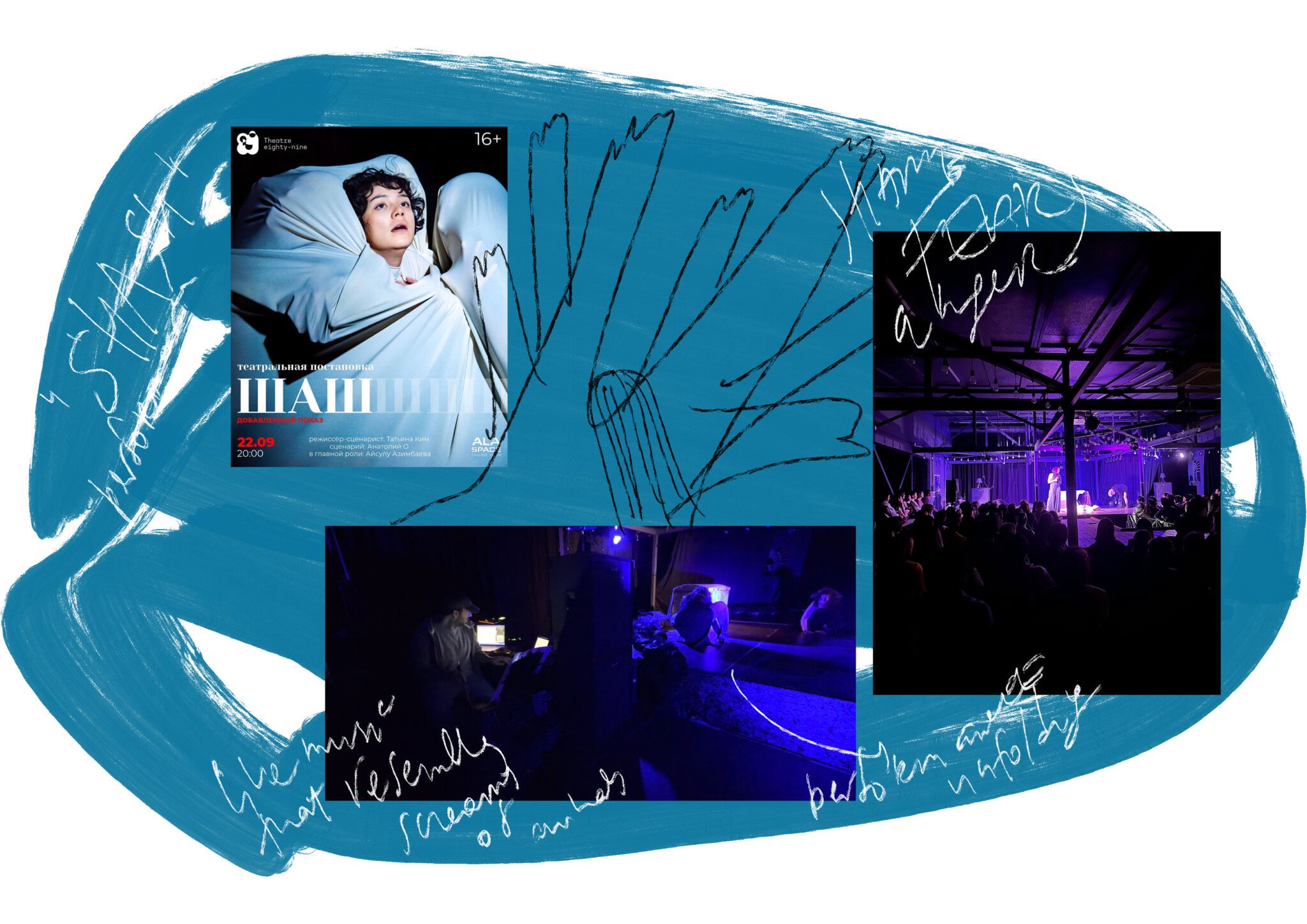

Their recent piece which premiered in Almaty in September 2023, drew attention to the internal dialogue that women carry within themselves as a form of transgenerational memory. Titled "Shash," this performance highlights women's engagement with the deepest corners of their subconscious minds—fears, shame, and anger—seemingly personified by the main character. Tormented and torn between these emotions, the main character ultimately finds a way to release them, recognizing that they are a part of her generational lineage. Embracing their presence as the fears, hopes, and desires of previous generations of women in her family brings peace to their spirits within the character's body and soul. "Shash" was presented at TEATRO89 and featured performances by Aisulu Azimbayeva, Ella Bayysbaeva, Madina Bespaeva, and Katya Dzvonik, accompanied by live music played on a the Daxophone by Eldar Tagi.

The live sound of the rare instrument—the daxophone—at times sounded like heartbreaking screams of a living being and at other times like squeaks of closing behind a door, symbolizing either the confines or the release of the main character. Live sound, in junction with mesmerizing women’s chanting, became an integral element of the performance, enhancing the narrative with its interplay of movement, emotion, shadow, and light, captivating the audience as the story unfolded before their eyes.

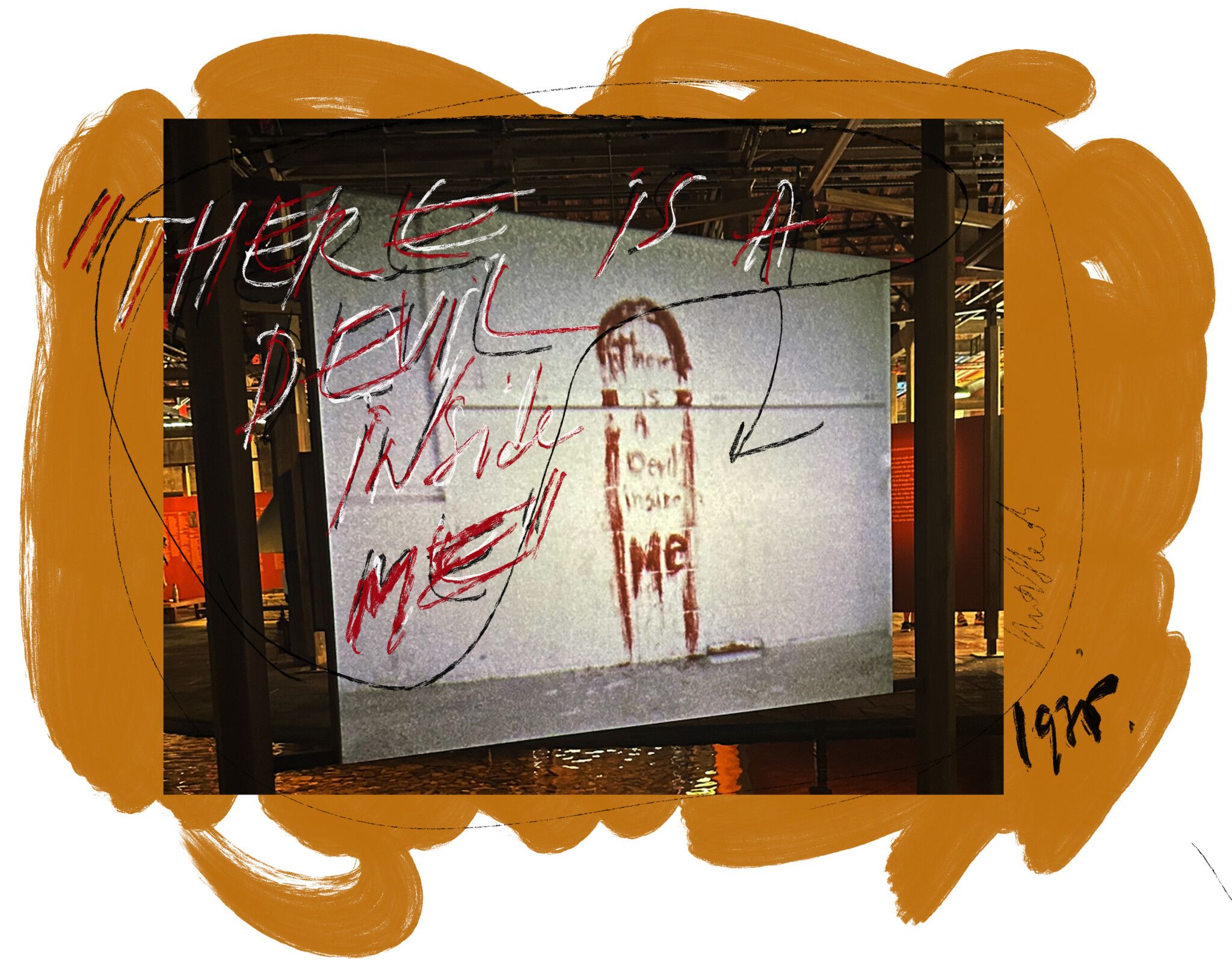

Fig. 23 "There is a Devil Inside Me," Mendieta’s work: Untitled, 1974, Super-8mm film transferred to high-definition digital media, color, silent; Copyrighted by The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong. Photographs taken at the show by the author (2023)

Fig.24 About the notion of shame. Tatyana Kim’s and Anatoliy O’s performance in Almaty, Kazakhstan, addresses the issues of domestic violence. A fragment of the show could be referencing the 2016 scandalous case when a citizen of Astana covered an artwork that featured explicit female features in order not to feel shame for the women. Image courtesy of performance stills: Tatyana Kim and Anatoliy O. Images of the sculptures are sourced from tengrinews.kz (2016) Collaged and annotated by the author (2023)

As the director explained, "I aimed to uncover the archetype of the modern mother-woman-girl who experiences a wide spectrum of emotions. This includes the scary and uncomfortable ones, often concealed beneath generational traumas and layered with the cultural context of Central Asia, situated somewhere between the Soviet mentality, social media, and a new era of self-awareness. We all exist somewhere in the midst of these complexities, and I sense that the city I find myself in now, along with its people, yearns not to be fragments of someone else's existence but to finally become whole."

With this reflection noted, and an audio recording made, I shifted my focus back to Ana Mendieta's art.

Self | Reflection

As I ventured further into the exhibition space, I encountered a section featuring Ana Mendieta's photographic work, which left a striking impression. Here, I could see images of Mendieta's face, adorned with hair forming a mustache. This imagery prompted me to contemplate the concept of assuming a masculine role—of seizing control over one's life and pursuing a career in the field of art, all while navigating the expectations and functions typically ascribed to women. It's challenging to believe that the artist wasn't confronted by conservatism and traditionalism during her time. What must it have been like for her? Was her playfulness in adjusting her hair to mimic a masculine image an attempt to convey her feelings? Perhaps she sought to convey how she was expected to feel, or maybe this concealment of her female identity, even if only for a photograph, signaled her rejection of the roles imposed upon her.

Fig. 25 "Shash" - Tatyana Kim’s and Anatoliy O’s performance in Almaty, Kazakhstan (2023) brought forth the questions of inheritance of archaic traditional culture that confines women’s self-expressions and constrains their liberation against oppression. The piece touches on ancestral roots, inter- and transgenerational traumas, and self-awareness. Image courtesy of performance stills: Tatyana Kim and Anatoliy O. Collaged and annotated by the author (202

Born in 1985, I distinctly remember my aunt recounting a conversation from a few years ago, revealing that my father had been deeply disappointed with the birth of a second daughter in the family. Yet, my mother always made it clear how cherished and loved I was, even though my father had anticipated a son. In my father's second marriage, when I was twelve, he finally welcomed a son, a situation that, for a long time, left me feeling as though my childhood had been stolen. Eventually, I made peace with the situation and even came to appreciate the advantages of my teenage years, liberated from the constraints of traditional and conservative fatherhood that once hindered my development. My mother often reminded me that in Kazakhstan, it was a common desire among men to have sons who could carry on the family name and lineage.

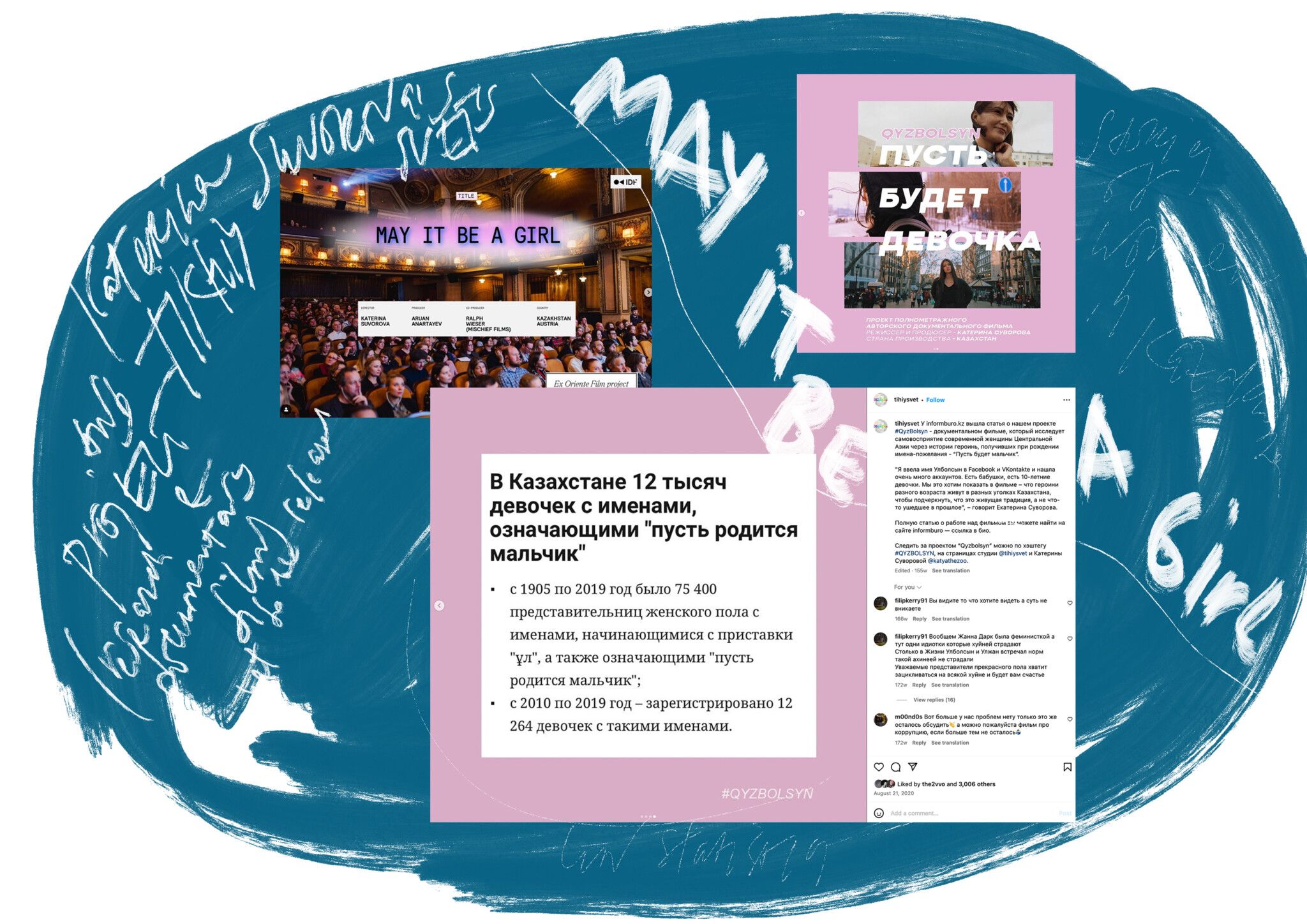

Gender inequality and archaic worldviews have persisted for centuries, and their echoes continue to impact the lives of women today. One poignant example of this inequality in contemporary Kazakhstan is Katerina Suvorova's documentary, "May It Be a Girl" (currently in production, with no announced release date as part of the documentary studio "Tikhyi Svet").

This film aims to shed light on the position of women in Kazakhstan and is the result of an extensive study of their role in society. Through personal narratives, the film provides a comprehensive answer to the simple question: What is it like to be a woman in Kazakhstan? The heroines featured in the film carry with them the stories of their names—Ulbolsyn (Ұlbolsyn), Ulzhan (Ұlzhan), Ulbala (Ұlbala), Uldarkhan (Ұldarkhan), Ultuar (Ұltuar), Ulbibi (Ұlbibi), Ulzhalgas, Ulbike (Ұlbike), Uldar (Ұldar), Ultu (Ұltu), Ultusyn (Ұltusyn), Ulmeken (Ұlmeken), Kyzdygoy, Kyztumas, among others—all beginning with the prefix "Ul-," which translates from Kazakh to "may it be a boy." In Kazakh tradition, these names all share a common meaning: "may the next child be a boy." According to the UN, between 2010 and 2019, 12,264 girls were registered worldwide with names starting with “Ul-” ("Ұl-)," which essentially means "may it be a boy." From 1905 to 2019, there were 75,400 girls born with names featuring the prefix "Ul-" (“Ұl-”). (Tikhiy Svet 2020)

Fig.26 "Facial Hair Transplant" - Mendieta’s work: Untitled (Facial Hair Transplant), Suite of seven color photographs, estate prints 1997 Copyrighted by The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong. Collaged and annotated by the author (2023)

Fig.27 "May It Be a Girl" - Katerina Suvorova’s work (as part of production with Tikhiy Svet) is a documentary that brings forth the question of how it is to be a woman in Kazakhstan. As part of the film, the director uncovers the lives of women who were given a name that starts with the prefix “Ul-” ("Ұl-)," which essentially means "may it be a boy." The film is yet to be released to a wider public but is already very much awaited by the audience.

"I imagined myself in the position of these women and wondered how I would have felt knowing that I was a second choice," reflects Katerina. After daughters, sons were often born in these families. Film director and producer Katerina Suvorova suggests that subsequent pregnancies may result from reproductive coercion: a daughter named Ulbolsyn obliges the mother to continue giving birth until a boy is born. The film does not seek to abolish the tradition but rather raises questions about the relevance of such practices in times not defined by war or existential crises. Rather than taking a stance, Suvorova believes that the audience should confront the reality faced by these women and hear their captivating stories—stories that are both simple and extraordinary, marked by moments of tragedy and humor. These stories define what it's like to live a life as a woman in Kazakhstan.

In September 2019, an open call was issued for women with names starting with the following prefixes:

Ұlbolsyn - let there be a boy

Ұlzhan - boy's soul

Ұluya - boy's nest

Ұlbala - boy

Ұldarkhan - generous, free boy.

Ұltuar - will give birth to a boy.

Ұlbibi - a lady-boy.

Ұlzhalғas - son will continue

Ұlbike - boy girl

Ұldar - boys

Ұldana - boy's wisdom

Ұltu - the birth of a boy

Ұltusyn - the birth of a boy.

Ұlmeken - boy li

Ұlkeled - the boy will come

Ұlkutem - waiting for a boy

Ұlmumkin - a boy is possible.

Ұlma - is it a boy?

Ұlkaida - where is the boy?

Kyzdygoy - enough girls

Kyzboldy - enough girls

Kyztumas - won't give birth to a girl.

Burul - turn around (Tikhyi Svet 2019)

On my end, I eagerly anticipate the release of the documentary as a window into the reality that has significantly impacted the lives of Kazakhstani women, including my own.

After sharing my personal story, I feel compelled to make a remark. My bloodline ends with me because I have no aspirations to bring children into this world. Nevertheless, I've chosen to retain my family name, inherited from my father. This decision may be a conscious rejection of the tradition of taking my partner's name, or perhaps it's a subconscious attempt to honor him.

Takeaways As I left the SESC gallery, I felt a profound sense of closeness and connection to Ana Mendieta's art. Simultaneously, I felt a deep bond with Kazakhstan and its women. My sense of connection extended to the women in Cuba, America, and Mexico, where Mendieta lived and created her work. However, it was in the distant Brazilian context that I felt a particularly strong sense of love and admiration for my mother, who continues to bear the cultural burdens inherited from both Soviet and Kazakhstani traditions with dignity and gratitude. The same traditions she inherited from her ancestry, from her land that she passed onto me, which grapple with in my daily life. In an instant, my heart swelled with admiration and reverence for my female ancestors and the burdens they carried.

During this moment, I couldn't help but remember Saltanat Nukenova, who tragically passed away in November 2023, along with many other women whose stories I've encountered over the years in Kazakhstan and abroad. My thoughts went to my dear friend Asya Tulesova and her courageous defense of older people, as well as her own defense against allegations made by six adult men accusing her of physical assault. I thought of the timely works of Tatayana Kim and Anatoliy O, and the impactful documentary work of Katerina Suvorova, which promises to shed light on the reality of women in Kazakhstan today and their connection to outdated traditions of the past. I couldn't help but reflect on those 12,000 girls whose names mean "may it be a boy." And on all of the other baby girls who were born in families that desired the birth of a boy.

As I exited the exhibition, I recalled that it was in 1985 when Ana Mendieta's life tragically ended, and the circumstances surrounding her death remain unresolved. That same year, I was born in distant Kazakhstan. Before sitting down to write this text, I grappled with the question of the relevance of my experiences as an artist, historian, and curator in Brazil and how they related to the context that drew my thoughts back to Kazakhstan. I wondered if these loose connections between such disparate lands had any meaning.

I turned to my colleague for advice, and she wisely encouraged me to follow my intuition and express myself freely. I am grateful for her guidance.

Leaving the gallery, I felt a profound sense of connection not only to my female colleague but to women all around the world—past, present, and future. We are strong, our bodies and spirits enduring and resilient, we are united, and we are free to act upon our feelings, desires, and dreams.

Addendum The text was submitted to ISSUES in December 2023. By the time the piece is published, during the trial of the high-profile case involving the murder of Saltanat Nukenova, a domestic violence law had been adopted in Kazakhstan (April, 2024).

Previously, according to Article 73-1 of the Code of Administrative Offences, causing minor harm to health was punishable by a fine or administrative arrest for 15 days. However, if the harm was caused to a person who is in a domestic relationship with the offender, the guilty party could get off with a warning. The same sanction (a warning) is also present in Article 73-2 - "Battery" (causing physical pain without harming health).

According to Senator Zhanna Asanova, in 2023 in Kazakhstan, as a result of domestic violence, 69 women and seven children died. There were more than 99,000 reports of domestic violence, with 2,452 crimes committed against children. (Forbes.kz, 2024)

References

“You Can’t Run Away from the Truth”: One Year Later.” Adamdar, 21 Apr. 2020, adamdar.ca/en/post/you-can-t-run-away-from-the-truth-one-year-later. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

8th March Kz. “Instagram.” Www.instagram.com, 12 Feb. 2022, www.instagram.com/8marchkz/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Akmullaeva, Aurelia. ““Уят болады!”: как стыд стал культурным кодом казахского общества | PSYCHOLOGIES.” Www.psychologies.ru, 11 Aug. 2023, www.psychologies.ru/articles/uyat-bolady-kak-styd-stal-kulturnym-kodom-kazakhskogo-obshestva/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Alimtayeva, Aruna. “Потомки великих: Правнучка Ильяса Джансугурова о самоидентичности, социальных проектах и казахском языке.” The-Steppe.com, 24 Sept. 2018, the-steppe.com/lyudi/potomki-pravnuchka-ilyasa-dzhansugurova-o-samoidentichnosti-socialnyh-proektah-i-kazahskom-yazyke. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

“Ana Mendieta: Silhueta Em Fogo | Terra Abrecaminhos.” Sesc São Paulo, Sept. 19AD, www.sescsp.org.br/programacao/ana-mendieta-silhueta-em-fogo-terra-abrecaminhos/. Accessed 20 Dec. 2023.

“Asya Tulesova Has Been Released.” Adamdar, 12 Aug. 2020, adamdar.ca/en/post/asya-tulesova-has-been-released. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Bunyan, Dr Marcus. “Ana Mendieta Imagen de Yagul.” Art Blart, 3 July 2014, artblart.com/tag/ana-mendieta-imagen-de-yagul/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

“Бывший министр Бишимбаев задержан по подозрению в избиении до смерти жены - Аналитический интернет-журнал Власть.” Vlast.kz, 9 Nov. 2023, vlast.kz/novosti/57493-byvsij-ministr-bisimbaev-zaderzan-po-podozreniu-v-izbienii-do-smerti-zeny.html. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

“Detained Director of Gastrocenter Where Woman Was Killed Is Brother of Ex-Minister Bishimbayev.” Akipress.com, 21 Nov. 2023, akipress.com/news:744199:Detained_director_of_Gastrocenter_where_woman_was_killed_is_brother_of_ex-Minister_Bishimbayev/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

“Estate of Ana Mendieta - Artists - Galerie Lelong & Co.” Www.galerielelong.com, www.galerielelong.com/artists/estate-of-ana-mendieta. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Feminita.kz. “Instagram.” Www.instagram.com, www.instagram.com/feminita_kz/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

“Kazakhstan: Activists Jailed in Criminal Probes | Human Rights Watch.” Human Rights Watch, 12 June 2020, www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/12/kazakhstan-activists-jailed-criminal-probes. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Kim, Tatyana . ““I’m Five Thousand Years” an Immersive Performance by Tatyana Kim.” Www.youtube.com, 24 Feb. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=_6Ge5zZxywc. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Matveyeva, Diana. “История феминистских митингов в Алматы.” Masa Media, 6 Mar. 2023, masa.media/ru/site/istoriya-feministskikh-mitingov-v-almaty. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

McGraa, Taylor. “Protest Hits Tate over Exhibition of Alleged Killer.” Dazed, 15 June 2016, www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/31568/1/protest-hits-tate-over-exhibition-of-alleged-killer. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

NGO Svet. “Instagram.” Www.instagram.com, www.instagram.com/svetpf/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

O’Hagan, Sean. “Ana Mendieta: Death of an Artist Foretold in Blood.” The Guardian, The Guardian, 22 Mar. 2018, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/sep/22/ana-mendieta-artist-work-foretold-death. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Ospan, Fariza. “Instagram.” Www.instagram.com, www.instagram.com/ospanfariza/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Oyan Kazakhstan. “Main Hearing of the Trial of Asya Tulesova 03-08-2020.” Www.youtube.com, 3 Aug. 202AD, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dl05IweYDDo. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Protest.korpe. “Instagram.” Www.instagram.com, 29 June 2020, www.instagram.com/protestkor.pe/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Rosenberg-Klainberg, Sofia . Ana Mendieta - Asian Diasporic Aesthetic Practice. Columbia University LAIC, madap.tome.press/chapter/ana-mendieta-2/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Rotenko, Ulyana. “В деле об убийстве Салтанат Нукеновой появились новые подозреваемые.” Press.kz, 12 Nov. 2023, press.kz/novosti/v-dele-ob-ubijstve-saltanat-nukenovoj-poyavilis-novye-podozrevaemye. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Shatayeva, Lyazzat. “New App Helps Almaty Residents Monitor Air Quality.” The Astana Times, 2 Feb. 2017, astanatimes.com/2017/02/new-app-helps-almaty-residents-monitor-air-quality/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

tengrinews.kz. “Житель Астаны накрыл скандальную скульптуру девушки платком.” Главные новости Казахстана - Tengrinews.kz, 16 Mar. 2016, tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/jitel-astanyi-nakryil-skandalnuyu-skulpturu-devushki-platkom-290828/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Tulesova, Asya. “Instagram.” Www.instagram.com, www.instagram.com/miroiu/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Tyo, Valeriya, and Yuwen Gu. “Cleaning the Air and Improving People’s Health in Almaty | United Nations Development Programme.” UNDP, 2022, www.undp.org/kazakhstan/blog/cleaning-air-and-improving-peoples-health-almaty. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Wadler, Joyce . “New York Magazine, Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta, a Death in Art, December 1985.” Gallery 98, 5 Nov. 2020, gallery98.org/2020/new-york-magazine-carl-andre-and-ana-mendieta-a-death-in-art-december-1985/. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Weiskopf, Anatolyi. “В Казахстане экс-министра обвиняют в убийстве. Что известно? – DW – 14.11.2023.” Dw.com, 14 Nov. 2023, www.dw.com/ru/v-kazahstane-eksministra-obvinaut-v-ubijstve-zeny-cto-izvestno/a-67399509. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

World Health Organization. “Violence against Women.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 9 Mar. 2021, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

World Population Review. “Rape Statistics by Country 2020.” Worldpopulationreview.com, 2020, worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/rape-statistics-by-country. Accessed 21 Dec. 2023.

Lena Pozdnyakova

Lena (b. 1985, Almaty, Kazakhstan) is an artist and researcher.