Tensile Paradise: Field Manual outlines a collective, itinerant method for constructing temporary tea rooms as social and spatial experiments. Combining principles from tensile structures, horizontal organization, and utopian political thought, the manual frames rope, knots, tea, and time as both material and social tools. We propose a “Tensile Paradise” as a mobile structure sustained through negotiated tension and cooperation. It integrates practical instructions with conceptual definitions, historical references, and reflections on collaboration, climate, and hospitality. This manual is both a how-to guide and a framework for practicing site-specific collective world-building.

Tensile Paradise Field Manual

Conferencia de los pájaros I, Mexico City, 2022. Photograph. Courtesy of Sala de Té.

Introduction

The purpose of this manual is to outline the concepts, conditions, and basic components required to create a tensile paradise out of everyday materials.

1. To gather people together, you must present a clear end goal. In creating a tensile paradise, you are building a tea room1.

a. A tea room is a place to serve and drink tea with others.

b. Tea is always free.

2. The promise of hot tea may not be enough to entice and motivate. This is fine, as there is a parallel goal: finding paradise2.

a. Unwalled paradise: While boundaries will undoubtedly be part of the emergent process of finding paradise, walls and fences are not.3 These boundaries are negotiated and permeable.

b. Itinerant paradise: A paradise that moves from place to place. While this movement affirms its existence in our physical world (ie, paradise is a place, not an allegory)4, it isn’t confined by permanent geographies or coordinates.

c. Tensile paradise: A tensile paradise recognizes social and physical tensions as sites of negotiation and productive collaboration.

3. Paradise is not synonymous with utopia.

Utopia is a term used in literature and political theory to describe an ideal society. Utopia, by definition, is something that can be strived for but never reached. When a utopian project is built around principles of exclusion, i.e., an “ideal” society free of certain ethnicities, sexual orientations, or health and disability conditions, it becomes a dystopia. Creating a structure collectively is a way to put into practice the utopian ideals of a society in which each one of us contributes according to our own capabilities and, in turn, is cared for according to our own needs. 5

Albrecht Dürer, The Expulsion from Paradise, from The Small Passion, 1510. Woodcut. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Junius Spencer Morgan, 1919.

Boulder with Daoist Paradise, Qing dynasty (18th century). Nephrite jade. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Heber R. Bishop, 1902.

4. The central premise of what you are building is that of an organized structure: one that is not prone to falling or collapsing.

a. Organized structures are constructed so that their individual components are arranged to interact with one another, resulting in overall structural stability.

b. An organized structure results from efficient collaboration among people within different cooperative units.

c. Creating an organized rope structure requires clear communication, planning, and execution. This will result in evenly distributed tension.

5. Typically, this is achieved most efficiently through a structured organization.

6. A structured organization is a group of people who work together by assigning different roles to different members. By assigning roles to the group’s members, efforts can be put towards smaller tasks that together make up the larger actions necessary to achieve a goal. Although members have assigned roles, no role is more important than any other, thus ensuring that hierarchies of power do not interfere with the group's functioning.

Materials and Components

This section lists the Materials and Components you will need to find and have available in order to successfully construct a rope structure.

1. Acquire adequate rope for the structure.

a. Rope is a fiber that is woven or twisted6, noted for its length. Used for attaching (see also: knots), hanging, holding, connecting, lifting, lowering, measuring7, sailing, building, recording information8, and many other purposes. Several ropes woven or tied together can form other tools and structures, such as nets, hammocks, and tents.

Use ropes to create the frame of your structure. This is done by achieving tension. Tension can be created through tying several anchor points together and connecting these to vertical supports. Tension can also be adjusted and redirected using pulleys.

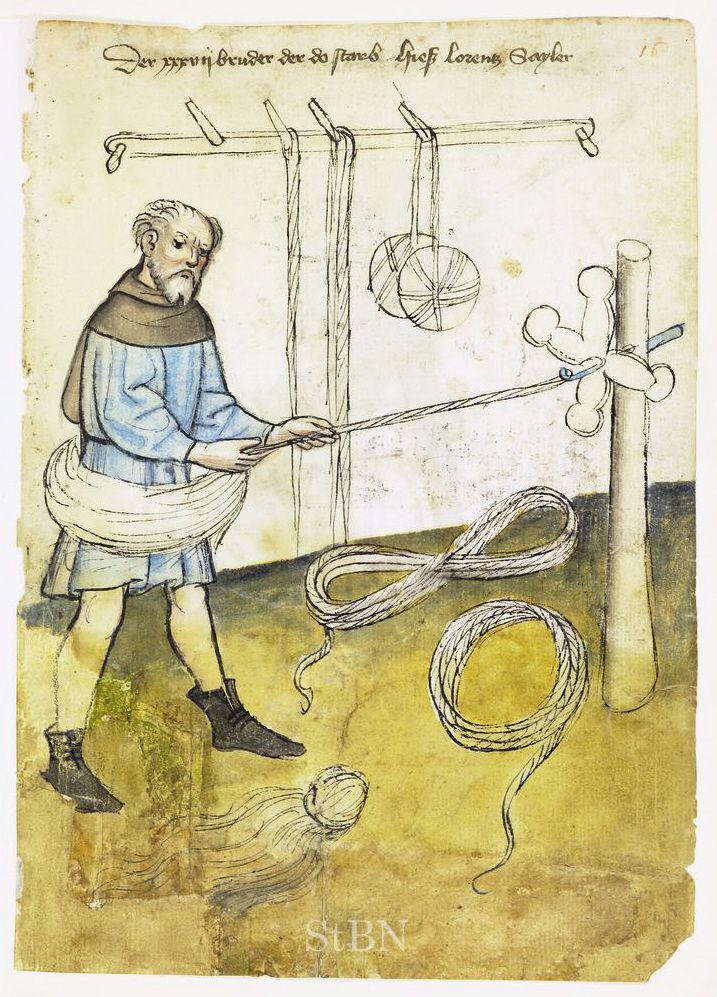

Anonymous, Ropemaker (portrait of Lorentz Sayler), c. 1425, from the Housebooks of the Nuremberg 12 Brothers Foundation, Archives of the Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg. Public domain.

2. All structures need supports at either end of a rope. These are also known as discontinuous compression units in tensegrity.

a. To create the vertical supports for your structure, tie down sturdy objects, such as metal poles, broomsticks, wooden beams, etc., so they remain upright even if disturbed by movement or touch. To ensure structural stability, tension has to come from all sides equally.

3. While it is possible to create a tensile structure by using only knots and readily available structures around you, such as trees or public infrastructure, you might also need a stake9 to secure ropes to the ground.

a. A stake is a stick you plant into the ground that, in becoming fixed to the earth, becomes an anchor point. Stakes are traditionally shaped so that the bottom part can wedge into or in between things, and the top part can be hammered in easily. They can take many different forms and are made of plastic, metal, wood, or other durable materials. Think of a stake as a giant nail that goes into the ground to hold things down.

4. This rope structure—this tensile paradise—is, as previously stated, a tea room. A samovar can be used to brew tea.

a. A samovar is a metal vessel10 used for preparing tea by heating and boiling water. The container includes a spigot for hot water and a chimney for releasing smoke and/or steam. A teapot with a high concentration of tea leaves is placed on top of the vessel, allowing for smoke and steam to maintain the brew’s temperature. Water is served from the spigot straight into cups to allow for varied concentrations and consistently hot beverages.

b. Ensure that there is ample access to water, necessary for brewing tea, washing hands, and cleaning used cups.

c. When brewing tea using a samovar, black tea is traditionally used.

d. The tea is often served in clear, preferably heat-tempered glass cups with handles, allowing one to view the depth of color of the drink.

Ismaʿil Jalayir, Ladies Around a Samovar, c. 1860. Oil painting. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

5. To boil water, energy must be released as heat; you will need to secure a power source.

a. A samovar might use scrap wood or pinecones11.

b. Or it needs electricity.

Sabritas on a Persian rug, Mexico City, 2026. Photograph. Courtesy of Sala de Té.

6. Provide floor or ground coverings such as rugs, blankets, petates, or other kinds of woven mats12.

Structural Concepts Below is a list of concepts and names for different parts of a rope structure. Knowing these terms is useful for acquiring adequate materials and promoting efficient communication between people building a structure.

1. Rope structures rely on knots to maintain structural integrity13.

a. A knot is an intentional complication of a corded line (see rope). It is made by interlacing, looping, and tightening a flexible line so that friction and tension lock the strands together. Knots serve a variety of purposes, both functional14 and decorative15. Popular knots that are useful for a rope structure include, but are not limited to: Bowline, Marline Spike, Clove Hitch, Two Half-Hitch, Versatackle, and Whipping Knot.

Lucasbosch, Bowline knot, 2011. Illustration. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 3.0.

2. A tensile rope structure may use tensegrity to make sure that all weight and tension are distributed and resilient. Tensegrity is a structural principle that uses a balance of tension and compression to create stable structures. Portmanteau of “tensional integrity,” coined by architect Buckminster Fuller.

S.Wetzel, Tensegrity, 2010. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0

3. Both physical and social tension are necessary when building a structure and as part of the structure itself. Tension can mean (a) Physics Force applied to a flexible object when it is being stretched. (b) Social A situation or mental state resulting from opposing viewpoints, miscommunication, or ambivalent emotions. It is important to:

a. Maintain physical tension using building elements and participant cooperation. Stones can counterbalance a rope that is attached to a tree, creating tension. One person can pull on a rope while the other ties a knot to an anchor point, maintaining this force, which is vital for structural integrity.

b. Identify social tension as productive or nonproductive16. Situational awareness of your cooperative unit members’ intentions and emotions is essential for maintaining social integrity. Sometimes it is best to speak of this tension out loud, while at other times it might be de-escalated indirectly. Tension that denotes differences in roles and responsibilities can be important for effective collaboration.

4. Use anchor points as a departure point when planning your structure. Anchor points are the parts of the rope structure itself that hold it down and provide tension.

This includes weights, stakes, and pre-existing structures in the environment.

5. Sala de té (tensile paradise, tea room, rope structure, etc) involves spatial and social horizontality. In its creation and use, we sit on the ground and grant each other the autonomy to manage ourselves without a strict hierarchy.

a. Spatial horizonality is parallel to the line where the earth and the sky meet (horizon).

b. Social horizonality involves working together or organizing without top-down hierarchies.

6. A frame18 is the skeleton of a structure. Frames can be covered with different materials to provide extra shade, insulation, weather protection, privacy, etc.

7. A structure19 is any kind of spatially aware object created through the use of physical materials. Typically, a structure creates a border between the space outside the structure and the structure itself. This can be walls, a roof, a fence, a ditch, a trench, etc. A structure creates an inside one can enter and an outside that lies beyond it. Structures can range from completely impenetrable to permeable.

8. Weights20 are heavy objects that pull or hold something down. Their density is high, and therefore gravity acts on them with greater force than the rest of the objects in the structure, pulling them towards the ground.

a. Anchor points can be created using weights. They can also be used to create counterweights.

b. To weigh something is to measure its weight. Metaphorically, to “weigh” a situation is to take note of all of its components and then draw useful conclusions about it based on these observations. It is important to weigh things such as fatigue, hunger, and interest levels, as well as expected weather, available time, materials, participant numbers, etc., in order to accurately make a plan.

9. Cooperative Units21 are the smallest divisible part of a productive and resilient organization. A cooperative unit consists of at least four people, each assigned one of the following four roles:

a. Communicator: Communicators serve as liaisons between the other three unit members. They ensure that everyone is informed at all times of the state of the project as well as of the next set of steps that are to be taken. Communicators should pay special attention to make sure that connectors, planners, and support members are all informed of each others' progress, plans, tasks, and needs. They should also keep track of the time allocation in relation to the progress of the overall project.

b. Connector: Connectors carry out the manual tasks needed for the project to take shape. They connect the plan to the action. In a rope structure connectors extend and tie ropes to each other to build the structure.

c. Planner: Planners think of and discuss an initial overall structure or project goal with the other unit members and then coordinate with each other to make sure that tasks are completed as planned. In a rope structure project, planners take into account anchor points, vertical supports and connections in order to make a plan that evenly and efficiently distributes rope tension. Planners need to survey the project's progress and detect any weak points in the construction process or any breakdowns in communication and adjust the plan accordingly as it progresses.

d. Support: Supports make sure that the overall project is structurally sound by acting as the unit’s on-site logistics hub. A support will keep track of resources and have materials, tools, and project information ready to go should it be needed by the other members. They also assist the other roles when extra labor is needed to ensure the smooth running of a project or operation.

Social, Temporal, and Spatial Conditions This section details the different kinds of actions, situations, factors, and dynamics you might encounter while working as a group building a tensile structure.

1. Collaboration22 involves working as a group of people to achieve a collectively predetermined goal. It involves planning, division of tasks, resource administration, and task execution.

a. To collaborate on building a structure, you need to get together with a team, source materials, develop a plan, divide tasks, allocate resources, and execute your construction plan.

2. In order to find resolutions to disagreements or problems when making a structure, one must first unravel the situation. Unravelling can mean to disentangle fibers, but also, to fall apart or become dysfunctional. It can also be used to talk about the explanation or investigation of a complex situation as it happens.

3. Structures are typically built outdoors. When this is the case, climate plays an important role in how this is done.

a. Climate resilience: the ability of people, places, and systems to absorb and recover (often through strategic anticipation and planning) from climate-related disturbances while maintaining essential functions

b. Climate risk: potential future problems caused by, or associated with, climate change. These can be both long-term shifts in ecosystems and/or extreme climate events.

c. Climate capitalism: A system in which climate risk is addressed while preserving practices that cause climate risk, such as: extractivism, private ownership, profit incentives, overall growth-oriented economic models23, etc.

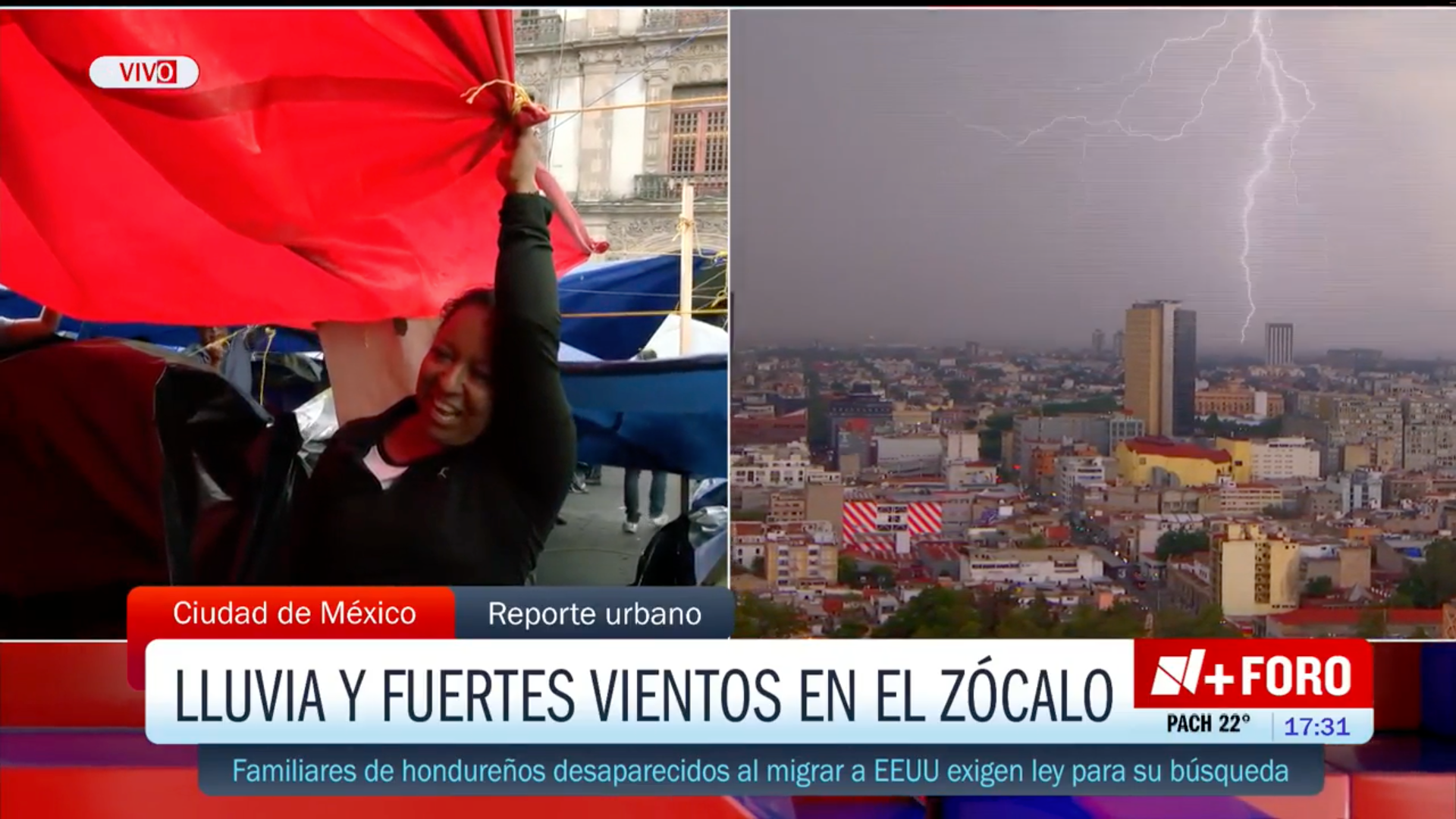

CNTE protestors sheltering under tarps during heavy rain, Mexico City24, 2025. Screenshot from N+, “Plantón de la CNTE Resiste Viento y Lluvia en Pleno Zócalo de la CDMX,“ May 21, 2025.

4. To organize effectively within a group, time must be estimated, tracked, allocated, budgeted, and coordinated in relation to each task and each person’s capabilities.

a. Time as a resource: Time is limited and unevenly consumed and is needed by different people for different tasks in different amounts.

b. “Our sweet time”: Idiomatic expression describing using time at a leisurely pace. Can have both positive and negative connotations depending on context. It is usually “taken.”

c. Metabolic time: Our bodies run on an internal clock tied to our sleep/wake cycle, eating times, and levels of caloric and mental energy. Paying attention to these levels ensures accurate planning and distribution of collective work.

d. Daytime: The duration of time, separated by dawn and dusk, in which there is available sunlight. Daytime varies depending on the season, the position of the Earth in relation to the sun, and one’s own position on Earth.

e. Tea time: a unit of time demarcated by the start/end of serving and drinking tea.

Research Bibliography

Ascher, M., and R. Ascher. Code of the Quipu: A Study in Media, Mathematics, and Culture. University of Michigan Press, 1981.

Ashley, C. W., and G. Budworth. The Ashley Book of Knots. Reprint edition. Doubleday, 1993.

Bellamy, E. Looking Backward: 2000–1887. Edited by M. Beaumont. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Bishop, Claire. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics.” October, no. 110, Fall 2004, pp. 51–79.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Translated by Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002.

Carrasco, Patricia. “Entre cobijas, zapatos y pertenencias mojadas amaneció el campamento de la CNTE en el Zócalo.” La Prensa, 3 June 2025. https://oem.com.mx/la-prensa/metropoli/ni-la-lluvia-los-mueve-campamento-de-la-cnte-en-el-zocalo-amanecio-inundado-23931080

Ching, F. D. K. Architecture: Form, Space, and Order. 4th edition. Wiley, 2015.

Fourier, C. The Theory of the Four Movements. Edited by G. Stedman Jones and I. Patterson. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Fuller, R. B. Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking. Edited by E. J. Applewhite. Collier Macmillan, 1978.

Gish, Dustin. “Xenophon’s Cyrus in Paradise: Hunting and the Art of War in Antiquity.” Classical World, vol. 117, no. 2, 2024, pp. 117–145. https://doi.org/10.1353/CLW.2024.A919923

“Glooscap.” New Brunswick Literature Encyclopedia. Accessed December 6, 2025. https://nble.lib.unb.ca/browse/g/glooscap

Gordon, J. E. Structures: Or Why Things Don’t Fall Down. Hachette Books, 2020.

Haghighian, Natascha Sadr. How to Spell the Fight. Cairo: Kayfa ta, 2018.

Harrington, J. The Commonwealth of Oceana and A System of Politics. Edited by J. G. A. Pocock. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Herrera, Pepe. “El junio más lluvioso en décadas deja huella en CDMX.” UNAM Global Revista, 28 July 2025. https://www.atmosfera.unam.mx/el-junio-mas-lluvioso-cdmx/

More, T. Utopia. Translated by P. Turner. Penguin Books, 2003.

Morris, W. News from Nowhere, or An Epoch of Rest. Edited by D. Leopold. Oxford University Press, 2009.

N+ / Foro TV. “Plantón de la CNTE resiste viento y lluvia en pleno Zócalo de la CDMX.” Las noticias 1700 (video), 21 May 2025. https://www.nmas.com.mx/foro-tv/programas/las-noticias-1700/videos/planton-la-cnte-resiste-viento-lluvia-pleno-zocalo-capitalino/

Peterson, Jeanette Favrot. The Paradise Garden Murals of Malinalco: Utopia and Empire in Sixteenth-Century Mexico. University of Texas Press, 1993.

Posadas, J. Les soucoupes volantes, le processus de la matière et de l’énergie, la science et le socialisme. Pamphlet, 1968.

Robillard, W. G., C. M. Brown, D. A. Wilson, and W. G. Robillard. Evidence and Procedures for Boundary Location. 6th edition. Wiley, 2011.

Thompson, E. H. Christianopolis. Springer, 1999.

Wells, H. G. A Modern Utopia. Edited by G. Claeys, with introductions by P. Parrinder and F. Wheen. Penguin Books, 2005.

Chaikhaneh (چایخانه) (tea=چا) (house=یخانه)

While this term is loaded with meaning, particularly for those who live in cultures influenced or governed by Abrahamic religions, it is still ripe for new interpretations.

This is in opposition to the terms’ etymology; the English word “paradise” meandered into this language via Latin and Greek, but its origins lie in Old Persian, /paridaydam/, 𐎱𐎼𐎭𐎹𐎭𐎠𐎶, meaning “walled enclosure.” The Greek philosopher Xenophon, recounting histories of the Achaemenid Empire that he observed as a military general in those parts, is generally credited as bringing the cognate into Greek. “The word thus signifies a walled-in park of royal proportions. Within the embankments of enclosures, wild animals were stocked and hunted, gardens and orchards cultivated, a royal palace and pavilions on

terraces built. To the ancient Persians the word ‘paradise’ was just used as a regular noun, sometimes plural in number.” (Dustin Gish, “Xenophon’s Cyrus in Paradise: Hunting and the Art of War in Antiquity,” Classical World, vol. 117, no. 2, 2024, 125). These mundane and polyvalent forms of paradise introduce ripe opportunities to revisit and expand upon the term in the present-day.

Planetary paradise, that is, paradise that exists on our own planet Earth, and is accessible to us mortals, is nothing new. Catholic missionaries in 16th-century Mexico believed that Eden was near. “The concept of a terrestrial paradise was perfectly suited to the Utopian ideals that profoundly shaped mendicant thinking on arrival in the New World. The outlook of the friars was buttressed by the generalized conviction that the Garden of Eden was physically located in the newly discovered ‘Indies.’” (Jeanette Favrot Peterson, The Paradise Garden Murals of Malinalco: Utopia and Empire in Sixteenth-Century Mexico, University of Texas Press, 1993, 138)

Participatory and collaborative art, along with work that falls within the bounds of relational aesthetics, is tightly bound to re-interpretations of utopian ideals. Nicolas Bourriard refers to the functional, pragmatic “microtopias” of his gaggle of relational darlings (Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, 2002); Claire Bishop finds that most of these so-called microtopias are still “predicated on the exclusion of those who hinder or prevent its realization” (Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October, no. 110, Fall 2004, 68).

The act of twisting fibers into rope is not merely a means of binding them together, but a way of shaping the strands to share the burden. As the braid twists, tension is distributed from fiber to fiber. Without this rotation, the shortest strands would have to carry the weight alone and would become weaker overall.

In Ancient Egypt rope stretchers compared the lengths of rope with distances measured on the ground to survey and measure property. (Robillard et. al., 2011)

Such as the Incan Quipú system which kept records using knotted cords. (Ascher & Ascher, 1981)

To stake a claim is a metaphorical phrase used to assert the stakers’ ownership over something. While this is often used in the context of land, stakeholders are entities (people, organizations, businesses, etc.) who are concerned with (involved or affected by) decisions made by an organization or company.

Originally from Russia, this technology is widely used throughout Eastern Europe, Western Asia, and Southwestern Asia. This vessel simultaneously serves as a domestic technology and a social infrastructure.

In the original iteration of the tea room, held at artist space compás 88 in July of 2022, the samovar was powered using locally available combustible materials. Sabritas-brand potato chips were used to initiate combustion. This was a pragmatic accelerant learned from survivalist instructional videos, where industrial starch and oil stand in for tinder. They were used to set fire to ocote (Pinus montezumae), a resinous pine native to central and southern Mexico and extending into Guatemala. The wood releases a strongly aromatic resin that ignites easily on contact with flame and has long been used as fuel. Its smoke functions not only as heat but also as an olfactory signal. These materials produce a hybrid fire whose smoke carries traces of resin, salt, and fat, binding the preparation of tea to local ecologies and contemporary circulations of knowledge.

Stories are told through the horizontal plane of floor coverings. Woven rugs, from palm mats to Persian carpets, communicate comfort, utility, and mobility. Visual designs can indicate a sense of (dis)placement; the chaharbagh (چهارباغ) four-part garden designs reflect highly designed aristocratic gardens separated by waterways or quadrilineal paths, woven paradises that stay in full bloom despite shifts in climate and regime; the more contemporary so-called “war rugs,” produced in Afghanistan starting from the Soviet occupation, grow out of this same tradition of depicting landscapes through fiber arts, but often feature complex botanical designs interrupted by cartoonish military helicopters and Kalashnikov rifles. More recently, these rugs have been colloquially dubbed in the West as “9/11 rugs,” as they shift their representations towards US military drones, contemporary cartographic views of the country from an F-16’s eye-view, and, of course, the downing of the World Trade Center in New York City. These artforms both speak to the lived experience of the artisans while also catering to the foreign export market, the Orientalist desire to own an uncanny depiction of oneself as Occupier, forged from Othered hands and symbologies.

Knot-making is central to the praxis that allows us to embody theory beyond the tangle of language. We are informed by the work of educator James R. Murphy, whose method of using string figures to teach math to students “a way to involve the hands in order to unfold the brain's potential to think abstractly and problem solve.” (Natascha Sadr Haghighian, How to Spell the Fight (Cairo: Kayfa ta, 2018), 6).

“At sea, the whole subject of knots is commonly divided into four classifications: hitches, bends, knots, and splices. A hitch makes a rope fasten to another object. A bend unites two rope ends.

The term knot itself is applied particularly to knobs (and loops, and to anything not included in the other three classes, such as fancy and trick knots).” (Ashley & Budworth, 1993 p.12). Splices are any kind of multi-strand knot.

Such as in crochet or Chinese knotting (中國結)

An example of productive tension are disagreements as to where to tie the rope; two people have different opinions on where the knot and anchor point goes. This allowed a third person to enter the discussion and use this tension and be decisive and determine the best option.

The structure uses public drainage infrastructure and metal rebar.

Traditional nomadic tents in Central Asia, such as yurts and gers, use dismantleable wooden lattices and tensioned ropes or bands to clamp the frame and fabric skin together. This allows the entire structure to be packed down, moved, and re-erected many times. Reusable frames such as festival pavilions, exhibition halls, and emergency shelters likewise depend on standardized members and joints. A single kit of parts can potentially be used to build multiple temporary spaces over time.

Many contemporary projects treat the boundary between inside and outside as flexible, using lightweight membranes, mesh, or cable nets instead of solid walls so that the “inside” is defined as much by microclimate and social use as by heavy enclosure (Ching, 2014).

Such as water jugs, stones, sandbags, blocks of concrete, bricks, heavy metal objects, or any other object

Though arising from distinct national and ideological contexts, whether anti-Shah Marxism (Iranian Fadai), WWII anti-fascist resistance (Partisans), revolutionary syndicalism (IWW), Brazilian landless activism (MST), Palestinian national-liberation (PFLP), white-nationalist gym culture (Active Clubs) or a rebranding of Fascism (Patriot Front); each of these formations organizes its base through cooperative, self-managed units (cells, committees, working groups, settlements, five- to twelve-people crews, six- to ten-people clusters, etc) that collectively decide tactics, share labor and resources, and federate horizontally into broader networks rather than relying on top-down chains of command. Because every action is planned within these self-run, self-contained cells, the structure can bend, split or be dismantled at will. This makes these types of social structures harder to target and also makes it easier for them to re-group or adjust if any part is compromised.

Comes from a Latin root that is roughly translated as common labor

Examples of this are the Prototype Carbon Fund, a World Bank initiative backing projects like Brazil's Plantar eucalyptus plantations for pig iron production, which generate carbon credits by claiming avoided coal use while displacing local communities and expanding monoculture forestry. Another example are companies that rate carbon offset projects for credibility using AI, thus enabling continued high-emission activities via data centre emissions while also preserving market-based emissions trading.

In 2025, CNTE, the left-wing dissident contingent of the National Education Workers’ Union (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores Educativos, or SNTE, the Mexican union for teachers which is the largest union in Latin America and the largest teachers’ union in the Americas) staged repeated protests and strikes in Mexico City as part of a broader national movement by dissident teachers for the abrogation of parts of the country’s 2007 educational reform law. They demanded better pensions and working conditions, and renewed dialogue with federal authorities. As part of this, they began building a dense encampment starting May 15th that served as both a living space and a protest HQ. Rather than erecting free-standing structures, the CNTE parasitized the city’s infrastructure, producing a distributed structural field of membranes (tarps, plastic sheeting, and fabric) held together through networks of tensioned ropes and cords anchored to the existing urban fabric. The encampment provided a space for radical horizontality in protest decision-making that spread through its paths and meeting spaces and unfolded onto a continuous ground plane. The reduced distinction between “public” and “private” in the structure’s low-lying roofs, raised pallet platforms, and the lack of fully separate spaces reinforced this horizontality, resulting in an architecture of communal disobedience. This resilient, adaptable architecture could withstand normal wind, rain, movement, and partial dismantling without collapse. However, the city’s notoriously heavy summer rains came early and were particularly intense that year, with the June rains being the highest recorded in the last 50 years, according to the Institute of Atmospheric and Climate Change Sciences (ICAyC). The ICAyC points to hotter oceans and a particularly powerful start to hurricane season, with multiple storms forming in succession, as the principal cause of this increase. Coincidentally, May 15th was not only the first day of the encampment but also the official start of the Pacific hurricane season. And so, despite the union’s chants of “NI LA LLUVIA, NI EL VIENTO, DETIENE ESTE MOVIMIENTO” (neither rain nor wind can stop this movement), the climactic conditions became too difficult for the encampment’s structures and ultimately became a central defeating factor in the movement’s effort to occupy public space. Tents flooded, clothes and supplies were soaked, and reports of spreading illness emerged. Although the CNTE’s improvised construction gave the plantón a high adaptability factor, there wasn’t sufficient collective knowledge of extreme climate conditions and architectures of climate resilience. Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum, repeatedly stated that she would not send law enforcement to remove the protestors. She didn’t need state violence; atmospheric conditions proved her greatest ally. The ICAyC points to the June 2nd rainstorm as the second-heaviest rainfall event in the city in June. The CNTE formally began dismantling the encampment on June 6th, despite not having achieved their policy goals.

Layla Fassa

Layla (New York, 1993) is a writer, archivist, translator, and independent researcher living in Mexico City.

Guillermo Martínez de Velasco

Guillermo Martinez de Velasco (Mexico City, 1988) is an artist, musician and political ecologist from Mexico City.