It’s hard to relate to an oyster, they have no brain and the most primitive of central nervous systems.

Oysters also have very little agency – producing pearls is their only defence mechanism. Oysters are slow like plants; they take between one and six years to make a decent sized pearl.

Every type of mollusc can produce a pearl, not a beautiful or a valuable one necessarily but some kind of pearl. They occur when a little piece of the outside, dirt or grit, gets inside the shell and starts to cause irritation, in response the mollusc coats the foreign object with the same hard material it makes its shell out of. The pearl develops its shine by being polished against the mollusc’s soft body.

I found that I could make pearls one summer after staying at a beach house with my partner. The trip was meant to be relaxing but we argued a lot that summer, grating on each other. We always seemed to be too hot, sunburned and hungover. After a week or so there everything was ingrained with sand. It seemed to permeate every piece of clothing, all of our food, the electronics, making the buttons crunchy. I felt scratchy in all cracks and crevices, rubbed raw and salted.

I started to notice the pearl about six months later, it was at the entrance to my vagina embedded in the soft tissue. I stood over a mirror and looked at it. It emerged glistening white between folds of pink skin.

The most valuable pearls of all are the naturally occuring ones. These are formed like mine, where the dirt has accidentally entered the mollusc. These coincidental miracles are extremely rare, much more common are farm-grown pearls. The natural pearl is so unusual is because for a mollusc to make one the irritant has to be specifically lodged in its gonads. If the dirt enters any other part the mollusc can expel it but if it is in the gonads it can’t get rid of it and instead must make a pearl around it to ease the pain of the irritant, like a blister. People who work in pearl farms spend their days injecting irritants into oysters hoping to hit the gonads.

This was probably also why I hadn’t grown a pearl before when I had got sand in so many other parts of my body. If pearls could grow anywhere on the body where grit and sand go then I would have them in my mouth like extra teeth, a crop in each armpit, pearls sprouting between my toes and encrusting my scalp like horns.

Every few days I would take a look at the pearl to observe its growth, as it got bigger it developed more complexity of colour. The colour of a natural pearl is determined by the lips of the oyster. Mine is mostly pink. Depending on how it caught the light it would also shine green, yellow, orange and black. It was quite beautiful. I began to gain weight and attributed it to the pearl; the part I could see I realised was just the tip and as the years go by it gets bigger with a more refined shine. The more I thought about pearls the more miraculous they seemed; to make a pearl is to nurture a piece of the outside in your body, to gestate a stone.

I tried to introduce more irritants in the hope that another pearl would grow. Eventually one did but smaller and much less impressive than the first.

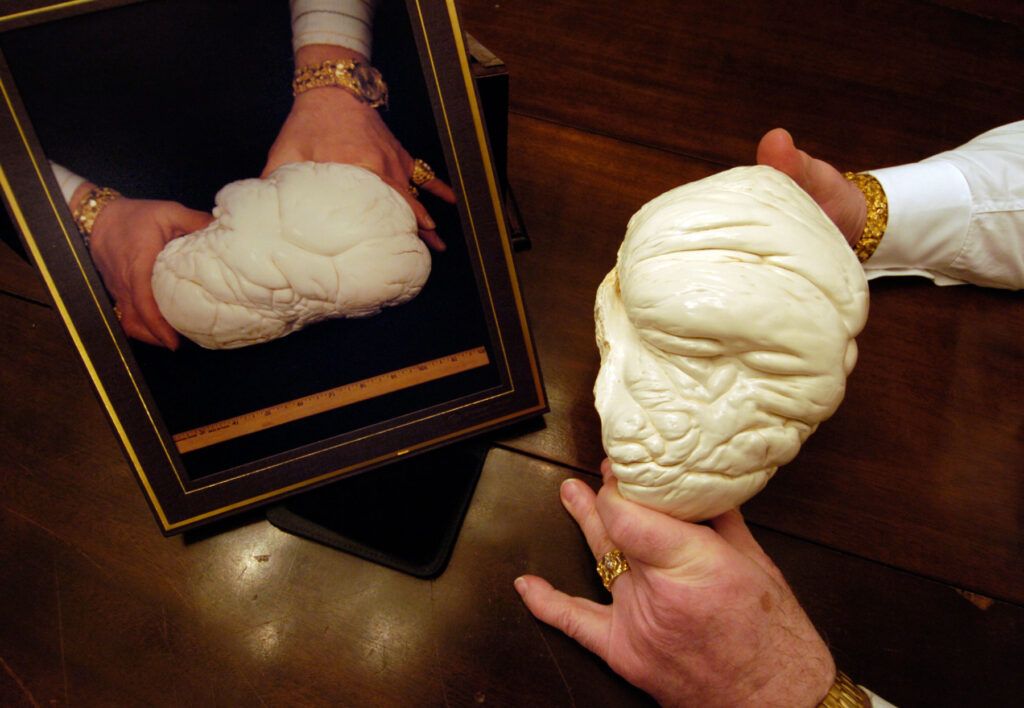

In my research I come across the Pearl of Allah, one of the biggest natural pearls ever recorded, it was found in 1934 by an indigenous diver from Palawan island in the Philippines. After the diver didn’t come back his fellow tribesmen went looking for him and found his body stuck within a giant clam. They brought it to the surface to retrieve the body and inside found a giant pearl. The Pearl of Allah is spectacularly large – 6.5kg but not conventionally beautiful, it has a matte texture, waxy, yellowish white colour and a rippled surface like a brain in formaldehyde.

The host mollusc is usually killed in order to harvest the pearl. Because of the sheer unpredictability of natural pearls, thousands of pearl-less molluscs will be killed looking for one with a pearl. I imagine my pearl, long after my body, my soft tissue, has disintegrated from it, it will remain. I imagine it sitting on the mantelpiece at the beach house, pieces of it chipped off and worn in the jewellery of future generations or encrusting a gown at the Met Gala.

Image: The Pearl of Allah. Image Credit.

Kari Robertson

Kari Robertson (b.1988 Edinburgh, UK) is a visual artist, teacher and researcher largely concerned with eco-social themes.

Wet Nurses, Microbes, Milk-siblings: Milk as Liquid Conduit

'Milk impregnated the particular atmosphere of women.' Read more

Entangled Pathogens - Interview with Dr. Lina Moses

'Moses utilises methods from both epidemiology and ecology to understand the interface of human, animal and pathogen.' Read more

On Shrinking

In a human lifetime the period in which we grow taller is relatively short, a maximum of eighteen or nineteen years. Read more