Tiny chameleon Brookesia micra sitting on a match head. Image Credit.

As we grow old we live smaller: lose friends, downsize, scale-back, and narrow our vocabulary.

This mirrors what is happening on a cellular level. Cellular senescence (the point where cells no longer reproduce) is a question of shrinkage; each time a cell divides the telomeres on the ends of each chromosome shorten slightly. At birth these extend to eleven kilobases, by the time we die they are as few as three or four. Cell division ceases once chromosomes shorten to a critical length, their minimum smallness.

Bigness is momentary and highly contingent; after we die we get rapidly smaller as parts of us are incinerated or eaten, melt away, or disintegrate. The human body, where bacteria and microorganisms outnumber human cells ten to one, ceases the metabolise, and the microbial life that has been populating begins to consume it.

‘Death is the loss of the individual’s clear boundaries; in death the self dissolves. But life in a different form goes on – as the fungi and bacteria of decay.’ (Margulis, 1997)

In death, the large organism makes way for the small.

Evolution is also a story about becoming smaller and simpler. Through generations, the human species gradually shed hair and lose no-longer-required organs; our teeth and bones become smaller and weaker. Physical capacities are lost – humans and other primates used to be able to synthesise vitamin C – as we continue to outsource what we need to our environment. Our repertoire shrinks.

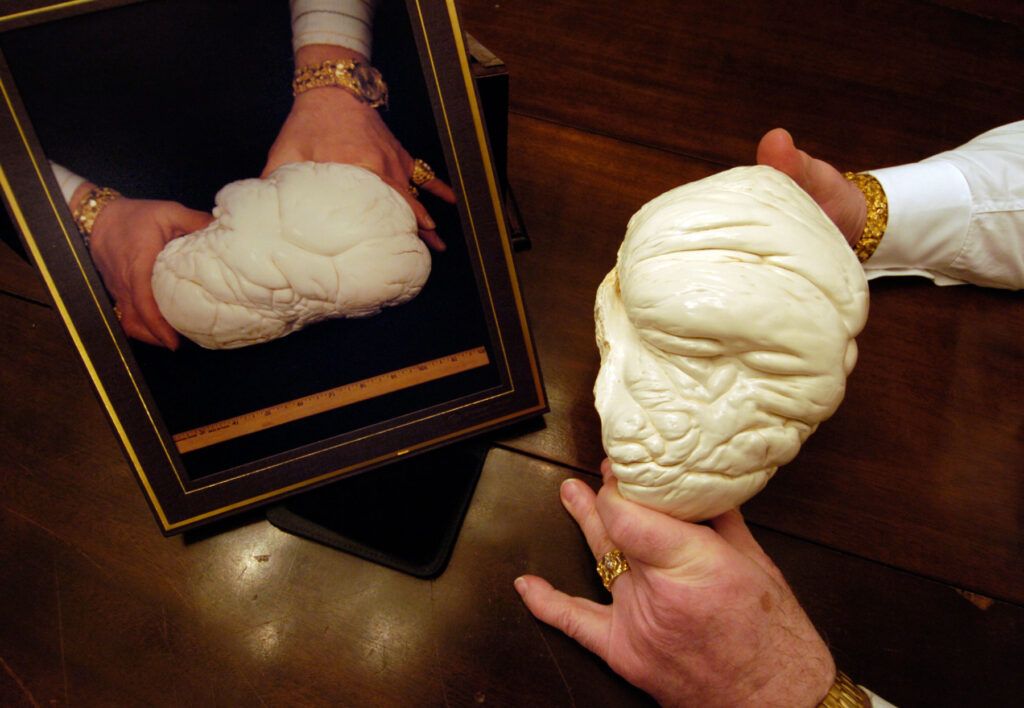

Animals evolve to be smaller in a process called miniaturisation. Large animals, being more conspicuous, are hunted more easily, while small animals tend to need less food to survive and so are less vulnerable to extinction. This process has produced, for example, a chameleon the size of a match head, a frog the length of a grain of rice, and a bat the size of a bumblebee. Miniaturisation as a process appears with greater prevalence in island habitats; a limited land mass creates downsized animals. These smaller versions of animals are also simplified as if the detail is tricky to downscale – they typically have fewer digits on their hands and feet, fewer skull bones, and less offspring.

Cells, in their composition with a nucleus and cytoplasm, were formed like this; at some point two free-living unicellular micro-organisms met and one elected to live inside the other. This process, symbiogenesis, is responsible for creating mitochondria in animal cells and chloroplasts in plant cells, which are both fundamental to cellular energy production.

Single-celled fungi reap the reward of profound smallness: eternal youth. Yeast and mould, as long as they have food and hospitable conditions, can live indefinitely. (Margulis 1997)

Small cells, rather than making their own food, parasite larger cells. In time they begin to shed the genes that allowed them to live autonomously as they no longer need them, until eventually they become large viruses. They shrink from being a living cell which eats, reproduces, and grows to a virus, a collection of genetic material, which requires a host cell to become activated.

Even atoms strive toward smallness. Their behaviour is influenced by the structure of the molecule they are constituting; the heavier and more complex the substance the greater their drive toward entropy. When they compose something large and complex, they try harder to split apart from it.

And with the splitting of the atom, the micro spectacularly collapses into the macro. In the engineered production of the inordinately, unimaginably small, we find the inconceivably enormous: the subatomic weapon, whose traces now ‘saturate the biosphere’ touching every continent, creature, and cell on earth. (Barad, 2017)

Offline References and further reading:

Barad et al. 2017 Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet_ Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press

Margulis, Lynn. 2008. The Symbiotic Planet A New Look at Evolution. New York: Basic Books

Margulis et al. 1997 Slanted Truths chapter 7: From Kefir To Death. Springer-Verlag New York, Inc.

Tsing, Anna. 2015 The Mushroom at the End of the World On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins New Jersey: Princeton University Press

Kari Robertson

Kari Robertson (b.1988 Edinburgh, UK) is a visual artist, teacher and researcher largely concerned with eco-social themes.

Entangled Pathogens - Interview with Dr. Lina Moses

'Moses utilises methods from both epidemiology and ecology to understand the interface of human, animal and pathogen.' Read more

Growing a Pearl

'It’s hard to relate to an oyster, they have no brain and the most primitive of central nervous systems.' Read more

Wet Nurses, Microbes, Milk-siblings: Milk as Liquid Conduit

'Milk impregnated the particular atmosphere of women.' Read more