Notes on “A dialogue must take place precisely because we don’t speak the same language”

The term “commons” is often traced to medieval England, where designated land held in common, such as pastureland, was protected from enclosure. This granted defined communities the right of use and access. Thus, the commons also established the identity of Anglo-Saxon communities—right-holders, known as commoners, who collectively govern and maintain the commons. More recently, scholars have coined the term “commoning” to emphasize the ongoing social practice of producing and reproducing the commons. Meanwhile, regardless of its etymological roots, practices of commoning structured around the self-governance of shared resources have existed for centuries in cultures all around the world. In effect, the recent energies and insights emerging from the common debate are fueled by a plurality of practices, and draw inspiration from work on decolonization and post-development, among others. But even as the commons framework expands beyond narrow discussions on the governance of material common-pool resources to include affective labor, immaterial knowledge or urban commons, the contemporary commons discourse continues to be rooted in the Anglo-Saxon history, culture, and language. This monocracy of the language of the commons presents a risk of further enclosure, confining the discussion of what we hold in common. How, we ask, can we access other worlds or rather enable other worlds to reveal themselves? How to translate commoning from one language to another? Or vice versa, how to make tacit traditional practices in other cultures translatable? And if we cannot critique the old world in the very language it was made, can translation play an emancipatory role? Can other words enable us to move beyond merely reproducing prevailing power structures? Or enable us to build another world?

It is with these questions in mind that we embarked on this project. But rather than lingering on whether the word “commoning” finds equivalence in another language, our attention soon veered to consider the very act of translation as a means of finding commonality. In fact, what is in common always only emerges in translation—the translation between different experiences, interests and subjectivities. Translation occurs at the intersection of differences, not their convergence. So rather than aiming for a precise mirroring of language that would imply the erasure of difference, translation is founded on and sustained through differences. Similarly, Stavros Stavrides states “translation inherently could invent commoning by reproducing views, actions, and subjectivities in translation (Stavrides, 2016)”.

Inspired by a passage from Sara Ahmed’s (2000) Strange Encounters: Embodied Others In Post-Coloniality, the project’s title “A dialogue must take place, precisely because we don’t speak the same language” prompts us to examine the Anglo-Saxon epistemology of the commons debate and shed light on the entanglement of power and knowledge at the root of contemporary research, education, and cultural production. By facilitating a dialogue about diverse practices and spaces of commoning, we believe this project aims to collectively building plural worlds of commoning. These dialogues unfolded in different formats, briefly described below. We then attempt to distill common threads from these conversations.

Exhibition website, displaying the essay of Guelaguetza by Tatiana Bilbao

Exhibition website

As of Oct 30, 2020, the website (adialoguemusttakeplace.org) features ten contributions in the form of written essays, images, audio, and/or a video, reflecting on a term that is closely related to the notion of commoning in the author’s culture. Contributors include Ghalya Alsanea; Ahmed Ansari; Tatiana Bilbao; Mónica Chuji, Grimaldo Rengifo, and Eduardo Gudynas; Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti; Jeff Hou; Eleni Katrini and Aristodimos Komninos; Joar Nango; Brook Teklehaimanot; Yoshiharu Tsukamoto. Some essays were written specifically for this project, other are republished. The contributions were curated by Stefan Gruber and Chun Zheng, edited and translated by Helen Young Chang, and the website developed by Yilun Hong.

The landing page is a collage of terms without beginning or end, juxtaposing ideas and allowing the reader to draw connections and bring the contributions into a virtual conversation. The layout is conceived in such a way to allow for new contributions to be added over time.

Online discussion with contributors

Dialogues

As part of the Tbilisi Architecture Biennale program and guided by its title “What do we have in common?” Stefan Gruber and Chun Zheng joined biennale co-founders Tinatin Gurgenidze and Otar Nemsadze for an online conversation about the project’s curatorial concept and research.

In November, as part of the School of Common’s public program, Jeffery Hou, Eleni Katrini, Aristodimos Komninos, and Brook Teklehaimanot joined Stefan Gruber and Chun Zheng for an online discussion around the notions of –作伙 (tsò-hué) in Hoklo Taiwanese, the lost meaning of‘κοινωνία’(kinonía) in Greek, ሰፈር (Sefer) in Amharic, and the大同 (Da-tong) in Classical Chinese. Based on their respective essays, each contributor presented their insights on the situated histories and diverse etymologies of the specific practice or space. The presentations were followed by a vibrant discussion on the implicit and explicit influence of language on the constitution of common interest.

A recording of both sessions can be viewed on the project website.

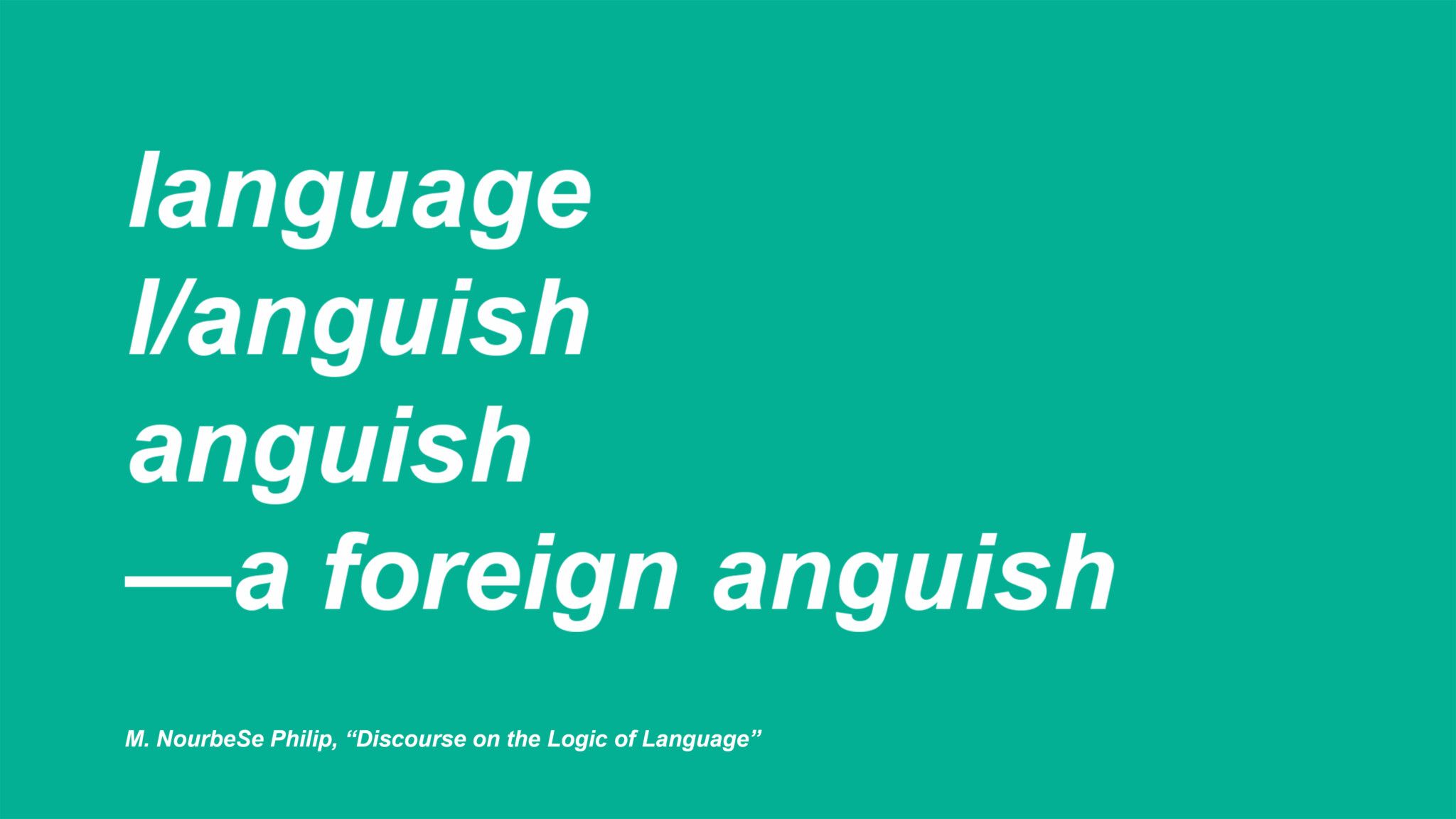

Workshop poster

Workshop: language l/anguish anguish —a foreign anguish

Inspired by M. Nourbese Philip’s (2011) poem “Discourse on the Logic of Language,” this public online workshop led by Helen Chang and Stefan Gruber invited participants to reflect on their personal relationship to the English language: What were the first fragments or sounds of words you recall in English, the first images you remember? What is your relationship to English now, who are you in other languages? How does the history of a culture shape language? How does that in turn shape us? Does this fact express who we are? With twenty participants form around the world, we considered the relationship of English to one’s mother tongue, as a source of connection as well as alienation. We called into question whether translation between English and the mother tongue is ever possible because even if we speak the same language, translation is constantly occurring. Drawing from a selection of poems and texts we discussed how English conditions knowledge and cultural production and reinforces structures of power both as a tool and weapon. This workshop was not recorded in order to hold space for an open conversation.

Notes on commonalities

Our lively exchanges, both written and verbal, have likely raised more questions than provided answers. However, when seen together, the contributions begin to weave the imagination of other possible worlds. In the following we draw preliminary connections between voices and identify common threads that emerge from the dialogues that took place.

- Practices and concepts of commoning are all around us, and can be found in traditional and contemporary cultures alike. From barely visible gestures to rituals passed down from one generation to the next, they comprise the relationships between humans and non-humans, the land, nature, the cosmos, and time. Joar Nango’s photographic tour across northern Finland, Sweden, and Norway portrays Sámi culture by capturing their ingenious creativity of repurposing local materials and everyday objects to sustain their lives in the extreme climate of the Artic. Here, Nango frames culture, beyond the binary clichés of indigenous traditions versus modernity, as valuable lessons in “indigenuity.” Against the backdrop of accelerating climate change, their whimsical, yet effective designs hold a wisdom that might serve us well as we learn to adapt to life in harsh natural environments. The South American concept of Buen Vivir resonates with the Sámi perspective, in that it emphasizes the interdependency of humans and non-humans beyond the dichotomy of society and nature. In their essay Mónica Chuji, Grimaldo Rengifo, and Eduardo Gudynas argue that Buen Vivir goes beyond the English notions of well-being or the good life as commonly interpreted. Buen Vivir is rooted in a deep understanding of nature and advocates for the equal rights of the more-than-humans world to exist, persist and regenerate.

- Most practices of commoning hold a material and immaterial dimension—the materiality of a shared resource or space, as well as the immateriality of shared purposes or beliefs expressed through social practices, behaviors, rituals or agreements. Yoshiharu Tsukamoto reflects on the reciprocal relation of architecture typologies and human behaviors. Over the course of centuries, buildings continuously adapt to human use, social norms and environmental forces. Thus, the material articulation and spatial organization of building typologies become the expression of social patterns or commonalities over time. But the built environment, in turn, shapes collective behavior. The practice of tsò-hué in Taiwan is a testimony to Tsukamoto’s point. Tsò-hué suggests a type of fluid togetherness in action. Jeffrey Hou describes how in the case of Taipei’s grassroots initiative Nanji Rice, implicit reciprocity, social connections, and mutual trust emerge from the collective practice of renovating and transforming a basement into a common space. “Tsò-hué in this case is a sequence of actions and sense of collective ownership, an experiment in sharing and community building.”

- These practices do not only relate to material and immaterial resources, but often actually blur the boundaries between the material and immaterial. The Arabic concept of Al-Mosha’ for instance refers to shared land ownership and shared activities. The Diwaniya constitutes a physical expression of Al-Mosha,’ as a room where Kuwaiti men meet, socialize and discuss politics. In her contribution, Ghalya Alsanea describes how the translation of Al-Mosha’ into the virtual sphere of social networks is enabling women to challenge the traditional gender and class divide that defines the Diwaniya as a patriarchal space. The transcendence of time and space can also be observed in the Sámi’s design hacks. Sámi people reinterpret vernacular practices and creatively apply the tacit knowledge to tackle present challenges. Their ability to sustain a traditional semi-nomadic life with contemporary means, connects them to the past and the present.

- Many commoning practices reveal ongoing power struggles. Be it the Al-Masha land in Palestine, the Da-tong ideology in China, or the concept of kinonía in Greece, all three have lost their original meaning under the influence of authoritarian regimes, neocolonialism, or consumerism. In effect, commons are subject to continuous appropriation and reappropriation, their relation to the state or market twists and turns. Al-Masha is the only type of common land that has survived the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, with their architectural practice Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency (DAAR) have been revisiting the notion of Al-Masha, seeking for new interpretations in the context of their design work on common spaces in refugee camps. Similarly, Chun Zheng attempt to revive the original Confucian notion of the Great Community, Da-tong, as a society structured around deliberative democracy. Over time, and for political purpose, its meaning was diverted to express unconditional unity. Reading Confucius’ original wording through a commons lens, Zheng calls for re-imagining Da-tong in contemporary China. Finally, in a conversation about kinonía, the Greek term for society, Eleni Katrini and Aristodimos Komninos depart from its most basic definition as a sum of free individuals, and describe kinonía as a way of being present, participating, and actively engaging in the making of a society. Thus, just as there is no commons without commoning (Linebaugh, 2008), in its original Greek meaning society is a verb. Its subsistence depends on continuous stewardship and social reproductive labor.

- While the role of architecture or design is, if at all, only implicitly discussed in most essay contributions, they all explore common space both as a shared resource as well as a place in which commoning unfolds. As much as we are eager to learn from the past and traditional commons, our belief in the agency of architecture and design for commoning in the present and future remains. We are not seeking a literal return to the traditional typologies or practices. Rather, re-inventing the meaning and function of the commons in the context of the now should be our designerly undertaking. As mentioned by Katrini and Komninos, as well as Tsukamoto, architects and designers need more practice to integrate commonalities into design, and furthermore, perceptions and behaviors of people who interact with the design.

As we engaged with numerous translations between languages and cultures, words and visuals, theories and practices, it became obvious that translation itself is a precious commoning practice. It constantly and actively produces and reproduces knowledge, reshapes the understanding of one language/culture and another, and challenges our reliance on the dominant English language and the Anglo-Saxon world. A question we have yet to answer: how to find the new words and worlds that allow translation as commoning to thrive instead of suppressing it?

References

Ahmed, S. (2000) Strange encounters: Embodied others in post-coloniality. London: Routledge. p. 180.

Khayati, M. (1966) Captive Words: Preface to a Situationist Dictionary in Internationale Situationniste #10 March 1966; trans. Ken Knab.

Philip, M.N. (2011) Discourse on the Logic of Language. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=424yF9eqBsE.

Linebaugh, P. (2008). The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All. University of California Press.

Stavrides, S. (2016). Common space: the city as commons. Zed Books.

Tbilisi Architecture Biennale 2020. Retrieved from http://biennial.ge.

School of Commons. Retrieved from http://schoolofcommons.org.

Stefan Gruber

Stefan is an architect, urban designer and Associate Professor at the School of Architecture of Carnegie Mellon University.

Chun Zheng

Chun is a landscape architect, urban designer and PhD researcher in the School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University researching practices of commoning and urban agriculture in the US and China.

Helen Young Chang

Helen is a writer, art critic and translator.