Our contribution aims to share what we have learned and maybe unlearned - including our thoughts on a long-distance bus ride, what we saw in a dream, or overheard in a conversation – during our time in School of commons.

The point of this text is to share a glimpse into what we have been up to during the past year, marked with different personal trajectories and the very non-linear ways in which we got to where we are now. It is a process with no intended end, in exactly the way we experienced it.

The theme of co-living was also not necessarily something we dug up from somewhere far away and attempted to dissect analytically. It was already quite present in both of our lives, so the attempt at making sense of it was a natural outlet for the many frustrations that came with participating in “the housing market”.

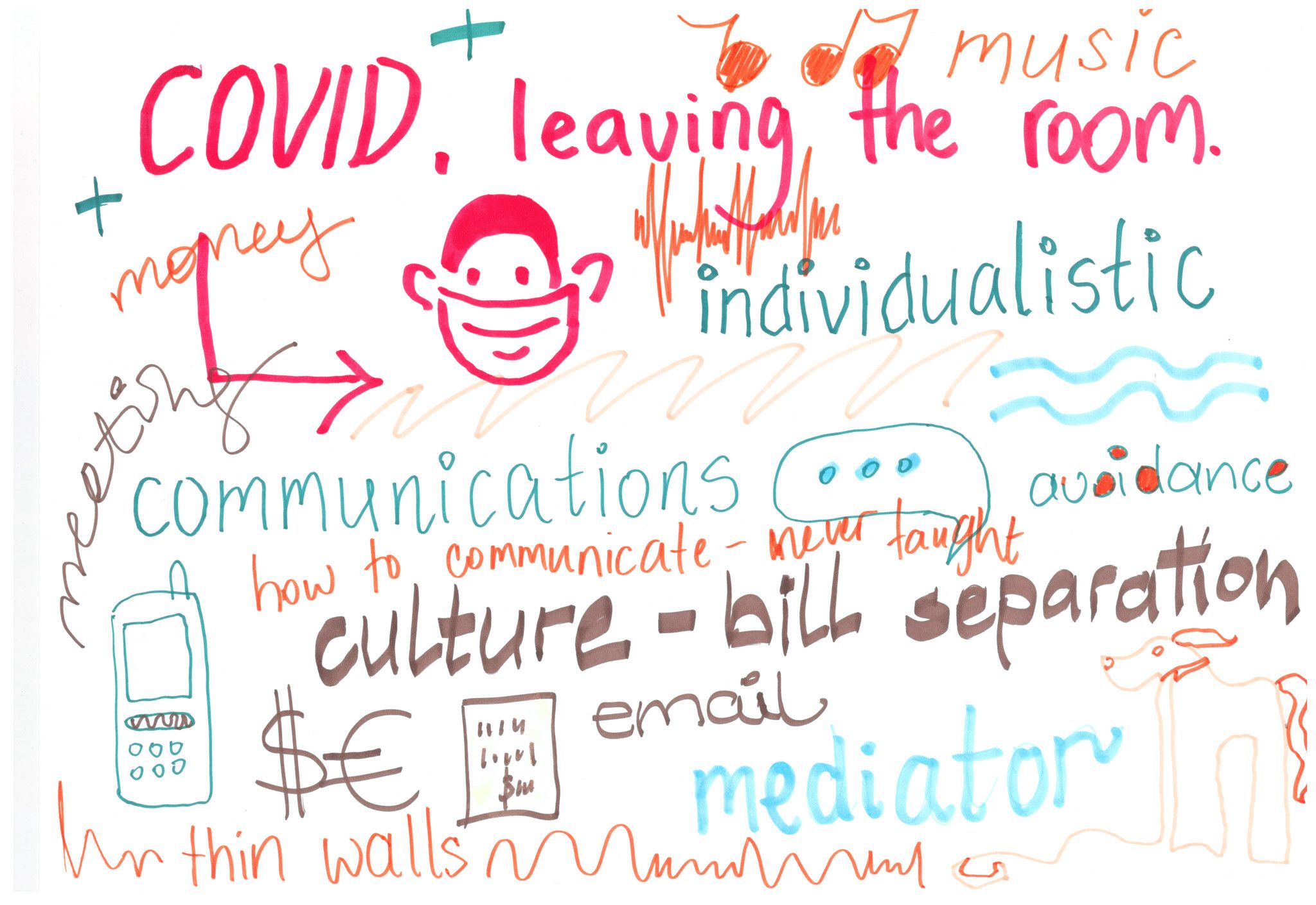

Financialisation of housing, housing as a commodity, or the “crisis” of housing are all academic tools to analyse broader processes happening around us. Despite our awareness of these structural causes for many years, we continue to experience the same, or even bigger despair every time we are trying to create a home or speak to others in the same situation. This situation understandably varies greatly across a spectrum of race, gender, class, sexuality, or migration background. For some, what is now being felt as a “crisis” by the white western middle class has always been the norm to others who sit outside of this demographic.

Resistance and alternatives to capitalist housing production are of course a reality in many places, including the contexts that we are in ourselves. Commons-based housing cooperatives like De Nieuwe Meent or De Warren in Amsterdam come to mind, as do a couple dozen legalised squats. Despite the inspiring stories of perseverance and collaborative efforts that usually stand behind such spaces, we don’t want to dedicate our focus to them, exactly because they will then remain exceptions. Most situations we’re in and around aren’t offered the same combinations of long-term security, affordability, and accessibility that usually come from well-defined collaborative missions backed by pre-existing long-term commitments and radical histories.

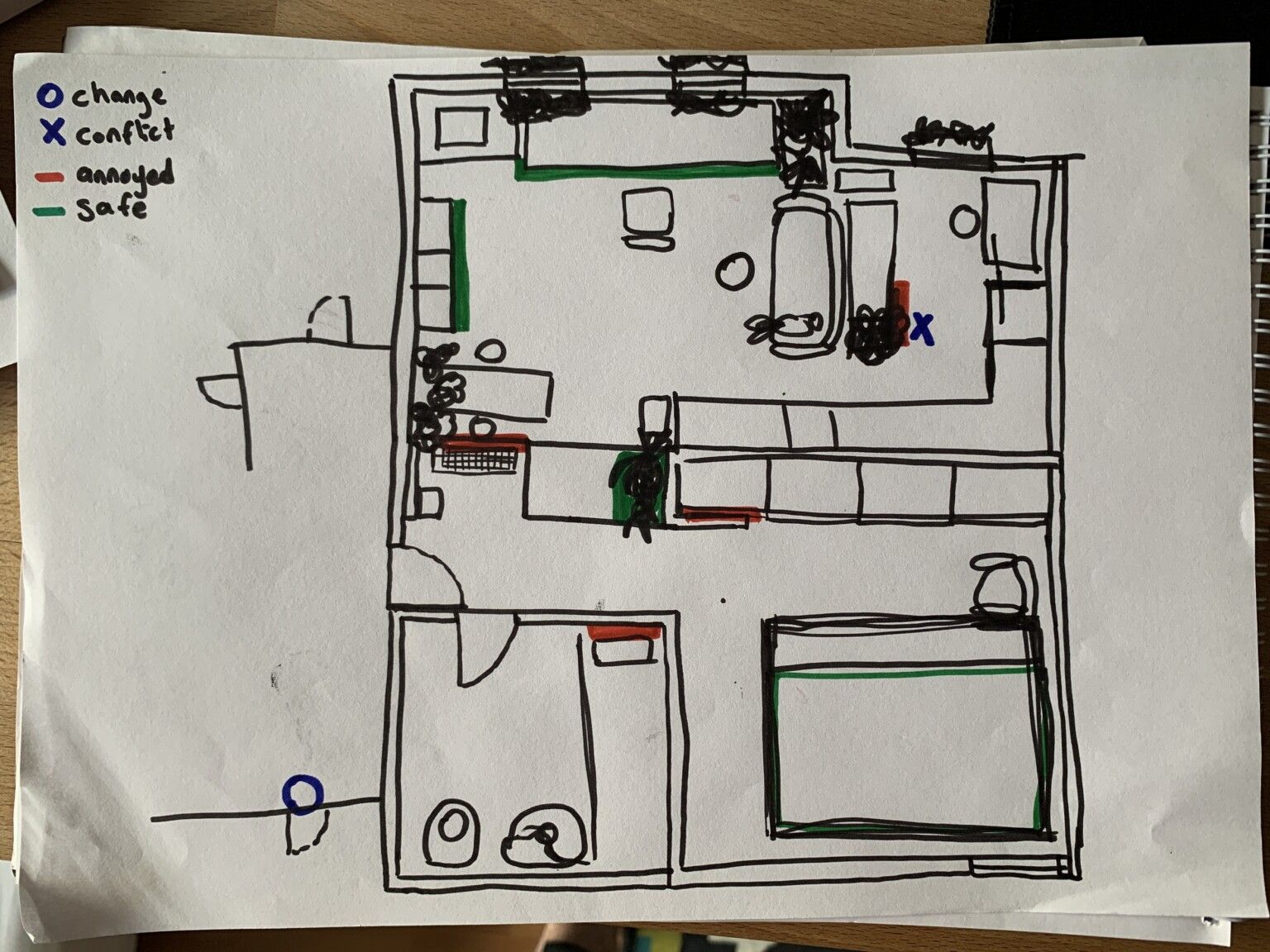

The places that we and our conversation partners find ourselves in are frequently way closer to the frustrating norm than that. At best they contain in themselves at least one of the usual suspects of housing in modernity: unaffordability and alienation through the lack of shared space and possibilities to communicate, living spaces inhabited or owned by hostile entities, not being given necessary space (either physically or otherwise), and precarity and temporality. In the worse cases, they contain nearly all the above.

It seems important to talk about possibilities in such situations, as we hoped the tools and approaches, we found could be broadly useful, and the conversations might be more inviting, as so many people would have something to share in relation to these issues and questions. Most related housing situations have a large influence on our daily lives: despite our location in them not being by our own preference - or maybe even because of it. Meaning we must find ways to talk about these issues, and to find tools and answers. We think it useful to consider our deeply flawed co-living situations to not be beyond hope and to not see our participation in them as passive but holding (at least a sliver of) potential for change. Through that we hope to see ourselves as (at least a little) able to enact a change, and (a bit) more empowered to make it a reality.

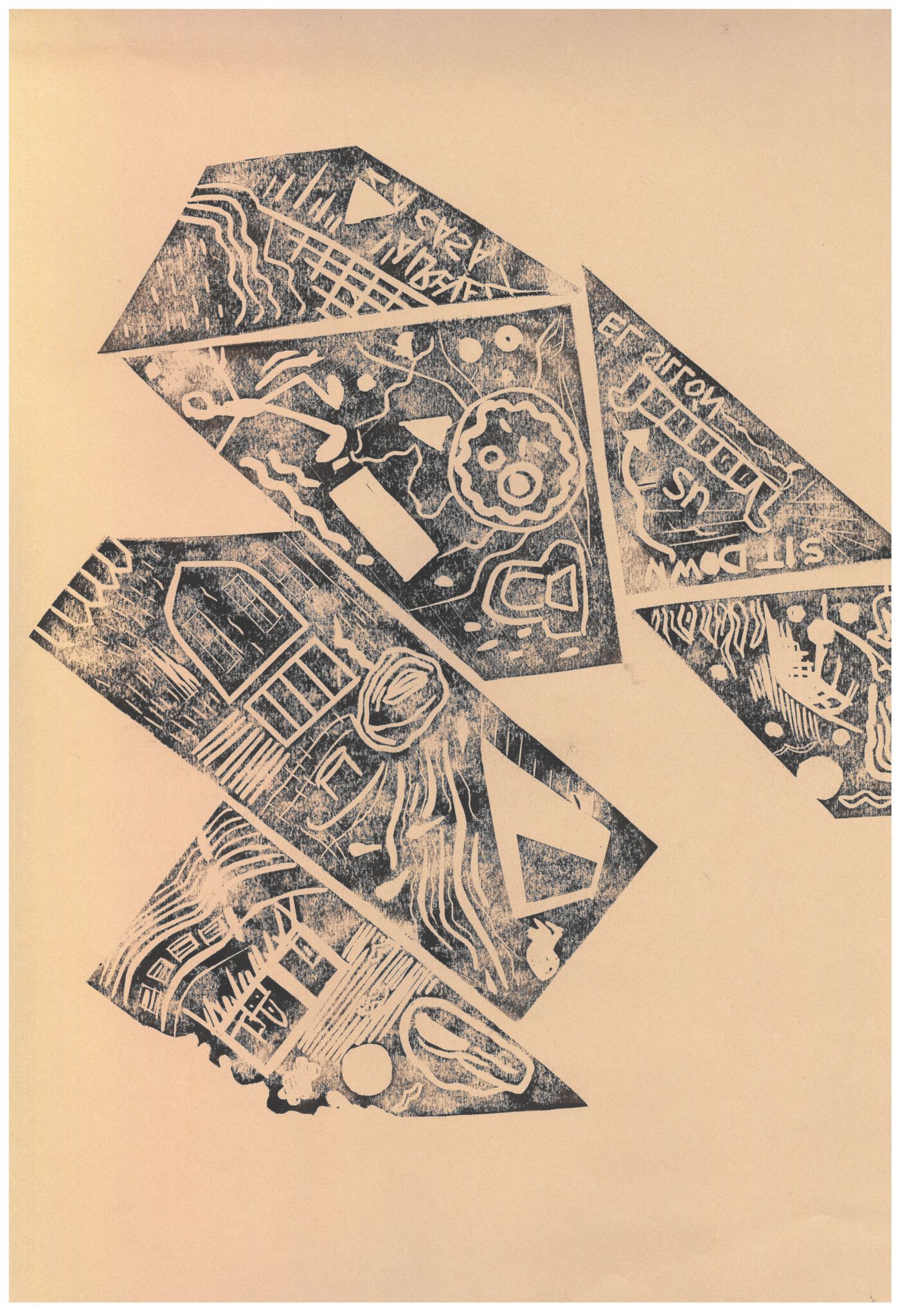

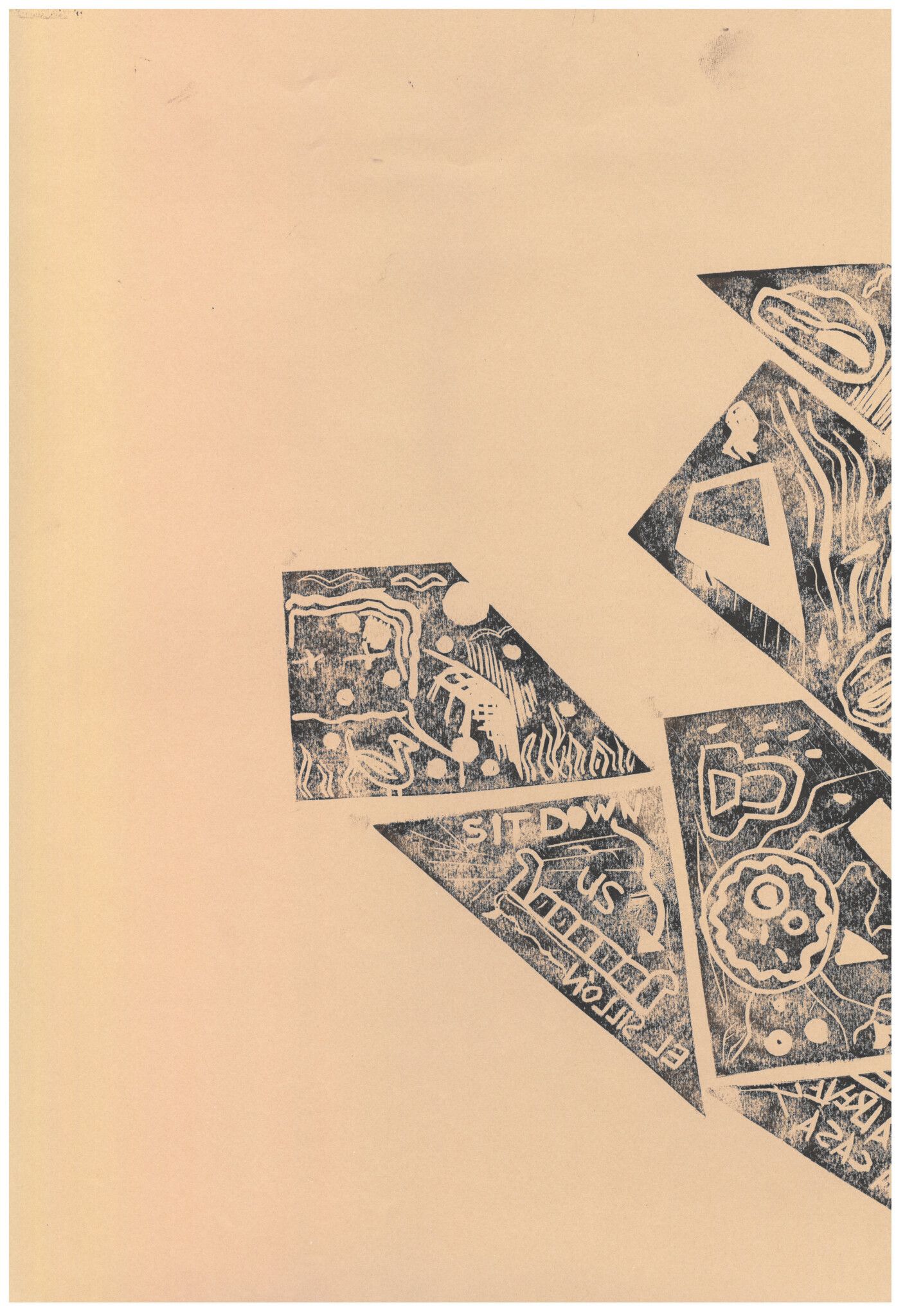

Hope for better alternatives undeniably goes hand in hand with imagination. No change can occur without imagining new radical ways of existing. However, before we start to come up with solid plans on how to resist capitalist production, and to talk of housing as commons, we must share our current practice and past experiences to see what we can, want and should bring with us into the future. And what better way to think of the future than through collective reflection and imagination? Through our collective struggles and problems, but also mistakes, we can learn how to create resistance that acknowledges structural problems, but also doesn’t forget the everyday. In other words, an argument over a stinky sponge can be more powerful than we think.

– approaches / ways and workings –

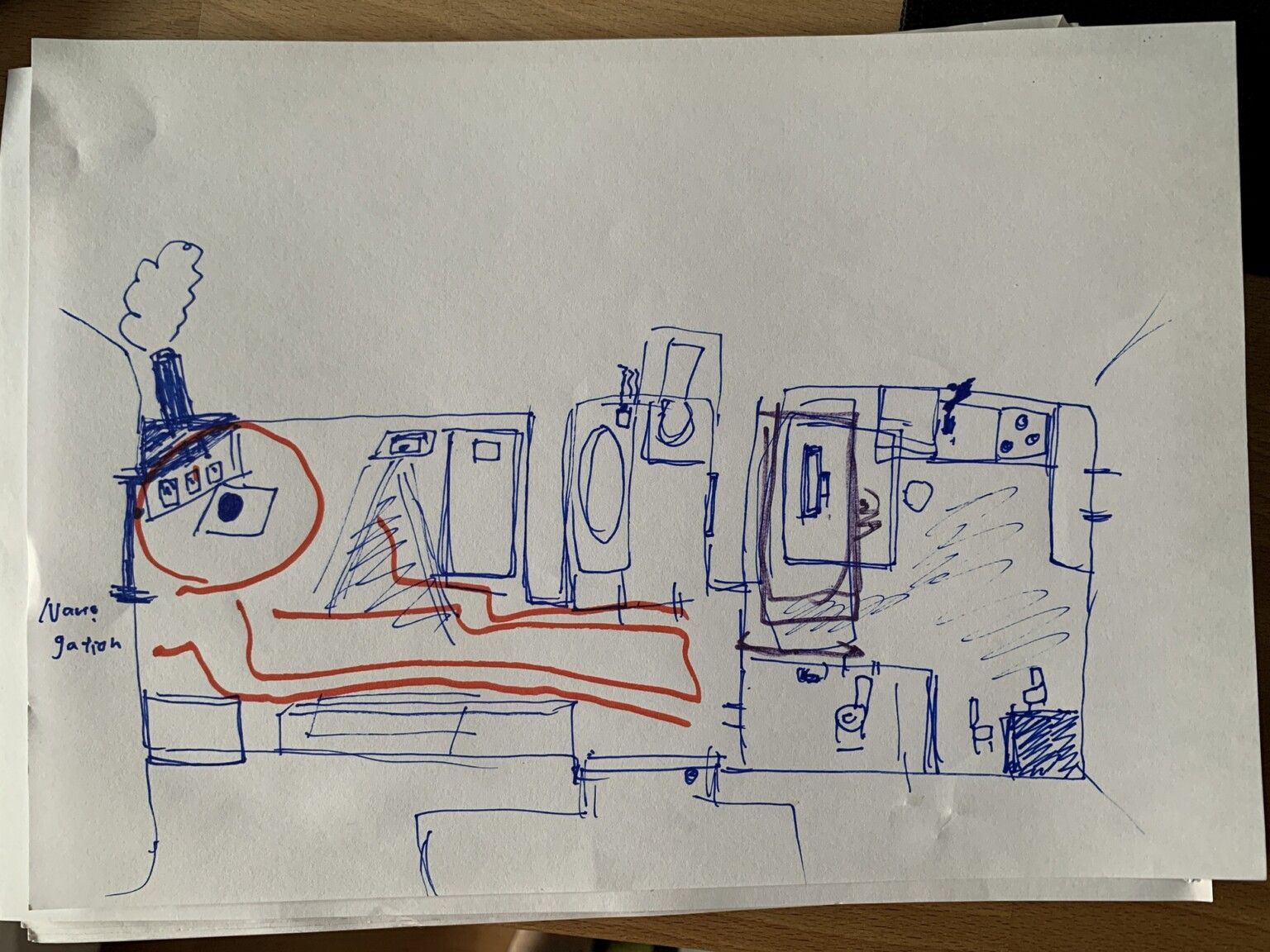

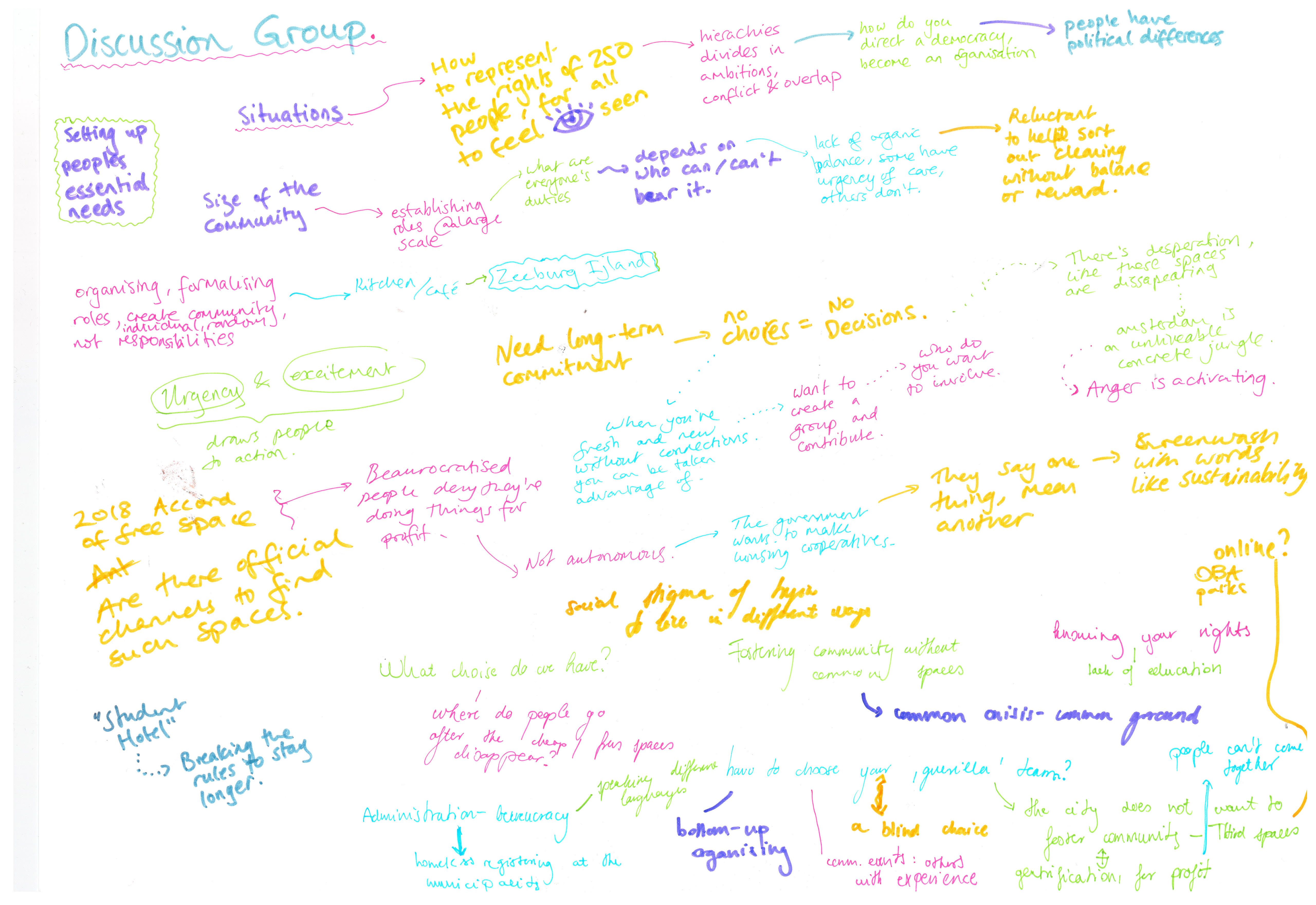

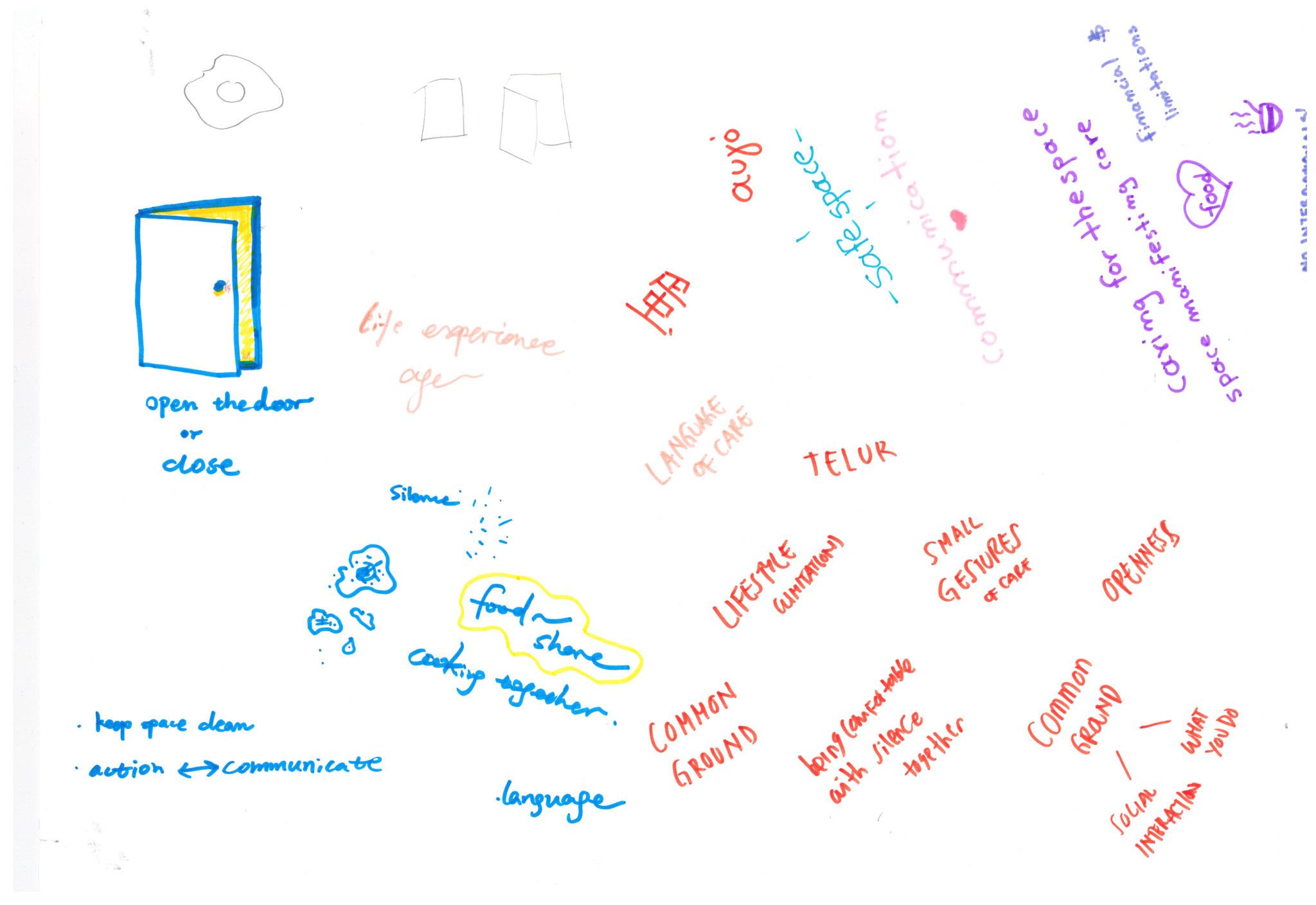

The idea to explore the topic of shared living situations began in a very informal setting, just talking in-between other parts of our lives, while biking in the rain, or waiting in line to get a pastry, or preparing to talk to a flatmate about the issue we were complaining to each other about. It initially appeared disconnected from any specific framework or goal, and because of that, we wanted to keep it that way. Exploration based, coming from a place of wanting to learn, from our peers and surroundings, more so than a search for a specific answer or solution. After all, the situations we encountered, and the people we spoke to, had their own widely different backgrounds and specifics, and yet were all equally as real, and as much standing to benefit from the sharing of knowledge.

Starting from personal interviews/talks/conversations with people engaged in collectives or projects that worked on alternatives to commodified housing, we aimed to map the personal and intangible of people’s living situations, the things that divide and connect them, and the elements that could make them evolve into the future. This process also involved conversations between us, reflecting on the things we consider important within our own co-living contexts and the situations we encountered. These formed the base for our conversations with people involved in co-living projects and, later, our workshops.