There, There: animal

We suggest activating the audio. Once you have listened to the Kazakh tale, begin reading.

Listen to the sound piece here.

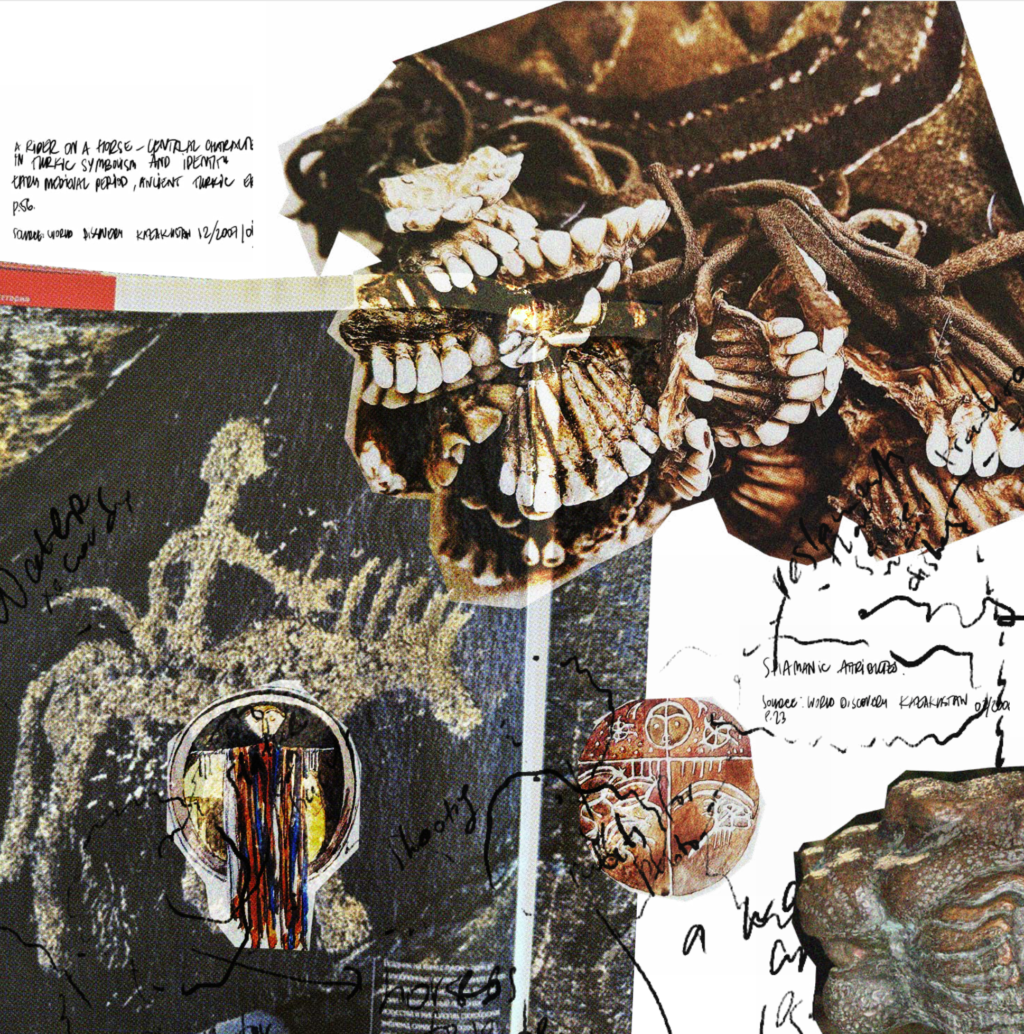

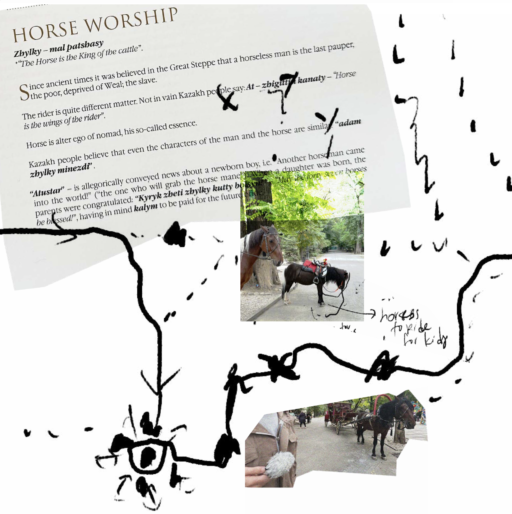

The inception of “Elephant in the Room” is rooted in a quest to understand the relationship between meat, animal products, and Central Asian identity—a linkage that seems inherent to those acquainted with the local culture. Historically, for the nomadic tribes of the region, reliance on animals was crucial. These tribes, utilizing animals like sheep, cows, horses, and camels, depended on them for sustenance, transportation, and clothing. Although modern lifestyles have dramatically evolved from the nomadic past, the cultural significance of these animals remains steadfast, and many of the century-old traditions co-exist with the contemporary reality of the region.

Kazakhstan, marked by vast landscapes and ranked among the largest countries in Central Asia, is also where my childhood unfolded, presenting a vivid mosaic of diverse cultures and traditions intricately interwoven. Its rich history is characterized by the dynamic confluence of nomadic tribal societies and industrial urban innovations, underscored by spiritual journeys from Tengrism to Islam, and transitioning from Soviet-inspired multicultural secularism to a unique and somewhat mysterious fusion of all these elements. This complex synthesis has cultivated a national identity as rich and layered as the varied strands of its historical fabric.

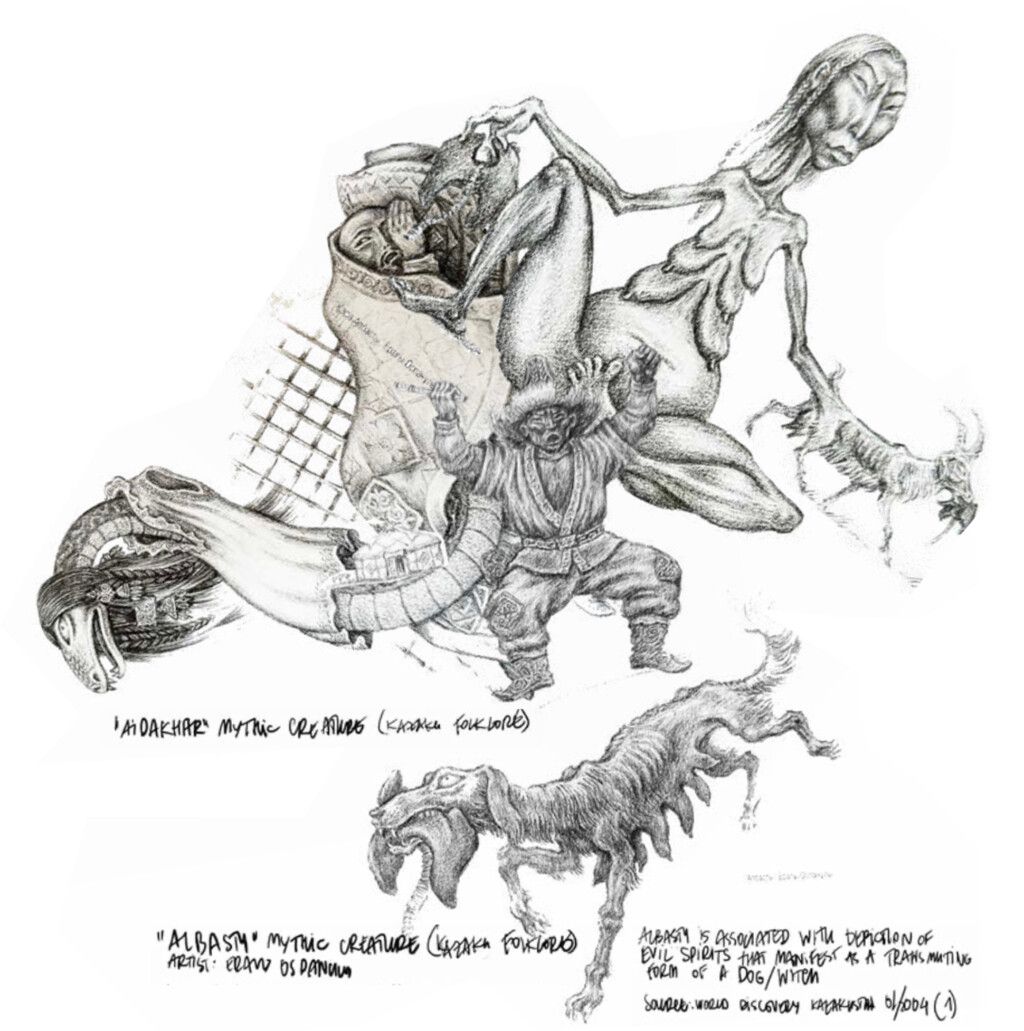

However, the transformations in cultural and social landscapes haven’t favored the animal kingdom. Over time, traditions have melded with the ideologies and demands of contemporary life, turning the once-revered sentient beings of our pagan ancestors into mere objects, subjugated by technology and stringent economic structures. The interaction between humans and animals in Central Asia, although deeply rooted in and informed by tradition, is now permeated with a touch of modern estrangement.

Traditions hold significance; they are mirrors reflecting our origins and encapsulating the narratives of a community. However, they are not immutable. As time progresses, the responsibility falls upon us to reconsider and potentially transform certain traditions, particularly those embedded with violence and exploitation.

In a world saturated with human suppression, the concerns for animals often seem secondary, largely overlooked or postponed. It appears as if a silent consensus deems animals the ultimate ‘other’—expendable for human benefit. Such a disposition neglects the inherent interconnectedness of the world, ignoring the repercussions of violence and suffering upon sentient beings, regardless of species. “The Linked Oppressions Thesis” proposed by a number of feminist philosophers suggests that various forms of oppression—whether racist, sexist, or species-based—are interlinked. Understanding one form of oppression requires an exploration of its connection to others, making the exploration of animal oppression crucial as it sheds light on overarching patterns of oppression.

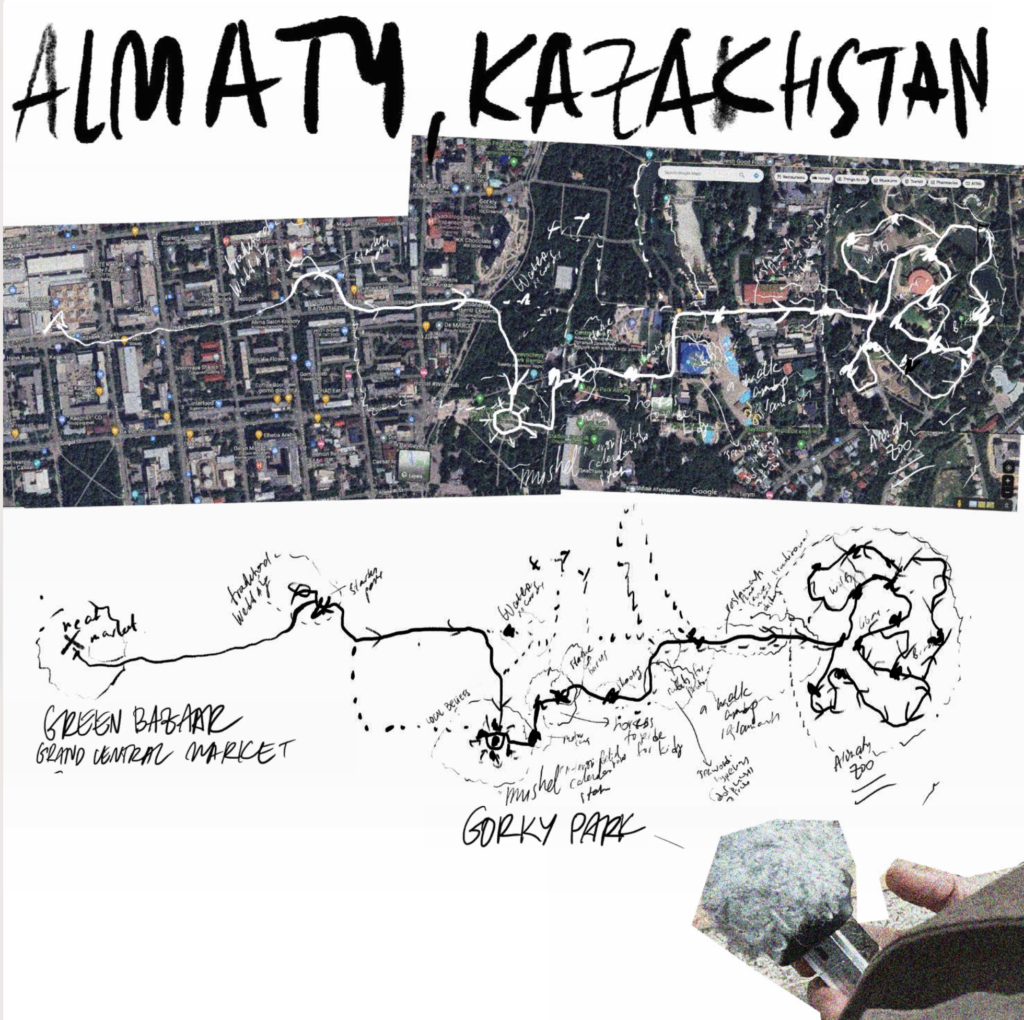

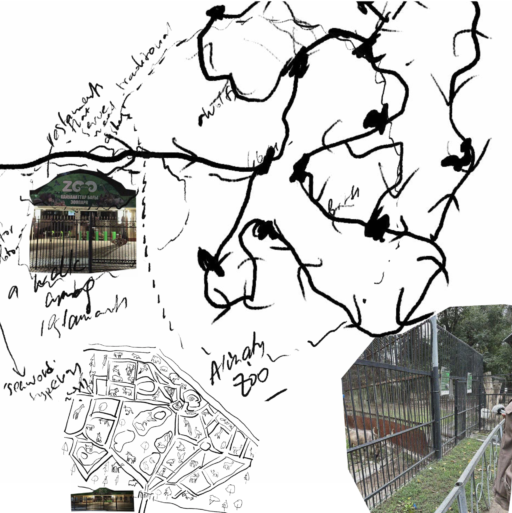

In “Elephant in the Room,” my exploration is focused on the ingrained patterns that normalize and anesthetize our relationships with animals, revisiting childhood sanctuaries like Almaty’s Gorky Park and the neighboring zoo—places that served as havens for observing the myriad creatures. The park offered a plethora of what then seemed like reasonable attractions, including horse rides, while the adjoining zoo provided opportunities to not only observe but also feed a variety of animals. Some inhabitants, like a particularly renowned brown bear, had become so accustomed to treats from the visitors that they adopted begging postures to charm the amused crowd into generosity. As a child, it was difficult to see this structure as problematic. Animals and people seemed safe separated by the bars of cages, and the concept of injustice could not be identified among the flocks of jolly parents and children.

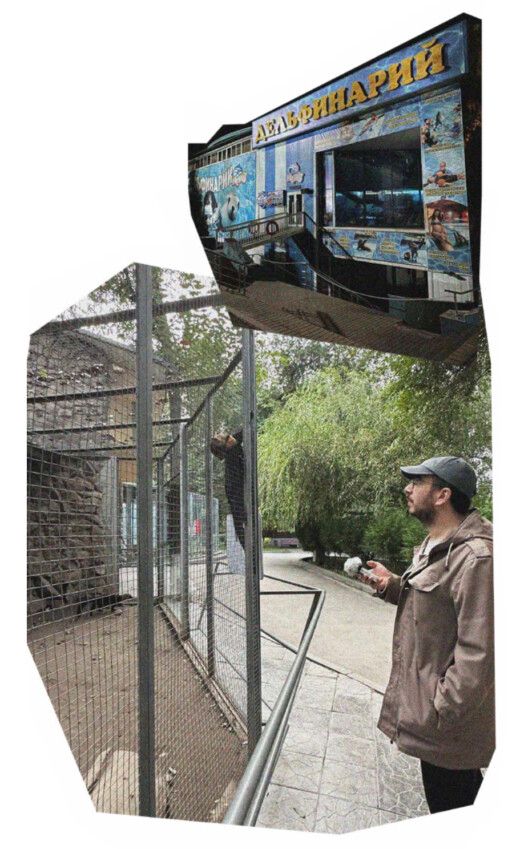

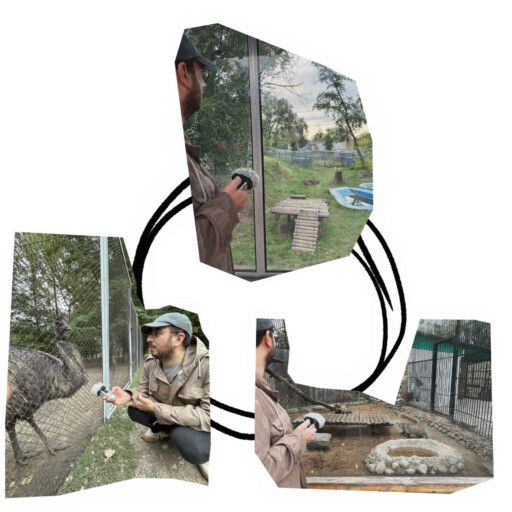

Decades later, retracing steps through familiar paths, my objective was to encapsulate the ambient essence and perceive the contrasts between my recollections and contemporary reality, using a “new” auditory perspective. Although the scene has evolved—the begging bear is absent, and a Dolphin Aquarium is shamefully added to the collection of exhibits—the fundamental spirit of the place endures. Families still gather; children and parents engage in discussions about the animals’ characteristics, and some venture to feed them, while the inhabitants contend with their confined quarters. A lion intermittently unleashes sequences of deep, resonant roars; and a host of other creatures, including porcupines, badgers, and tigers, pace anxiously within their enclosures.

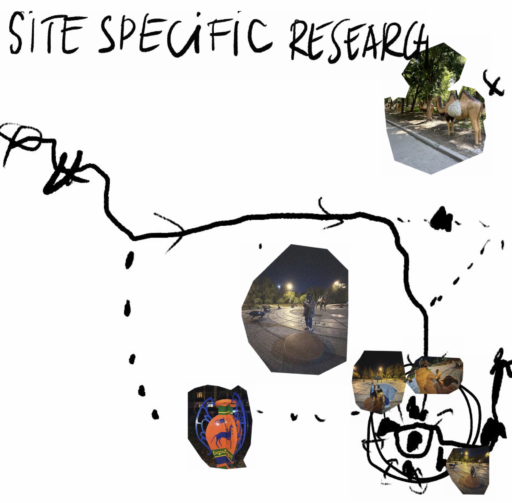

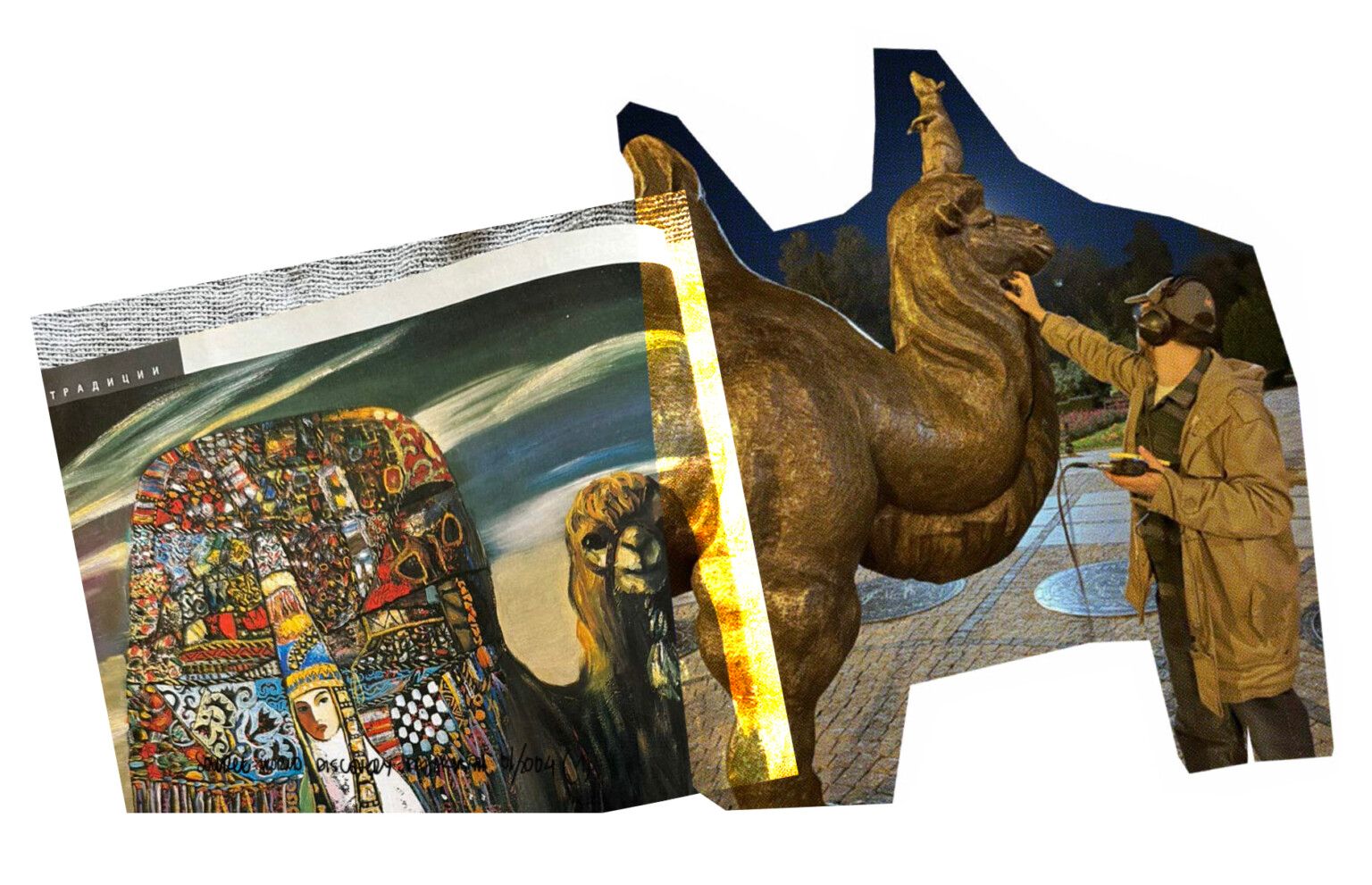

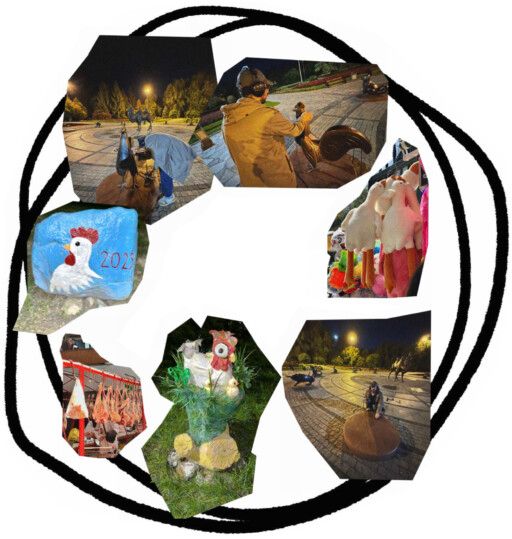

Fig. 12 The life of a camel. The camel is another revered animal in Turkic mythology and Kazakh culture. In public art composition, the camel, together with the mouse, takes the central role. The illustration is sourced from World Discovery Kazakhstan (2004), and the photograph of field recording is by the2vvo (2023); Fig 13-21 (smaller icons above) Soundwalk. Site-specific research in Almaty, Kazakhstan and documentation of recording process. Image courtesy the2vvo (2023)

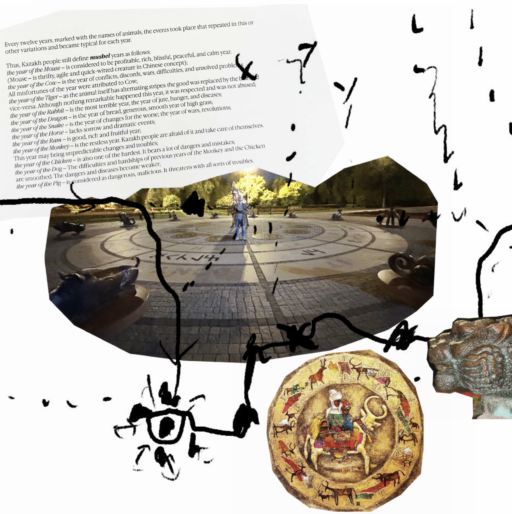

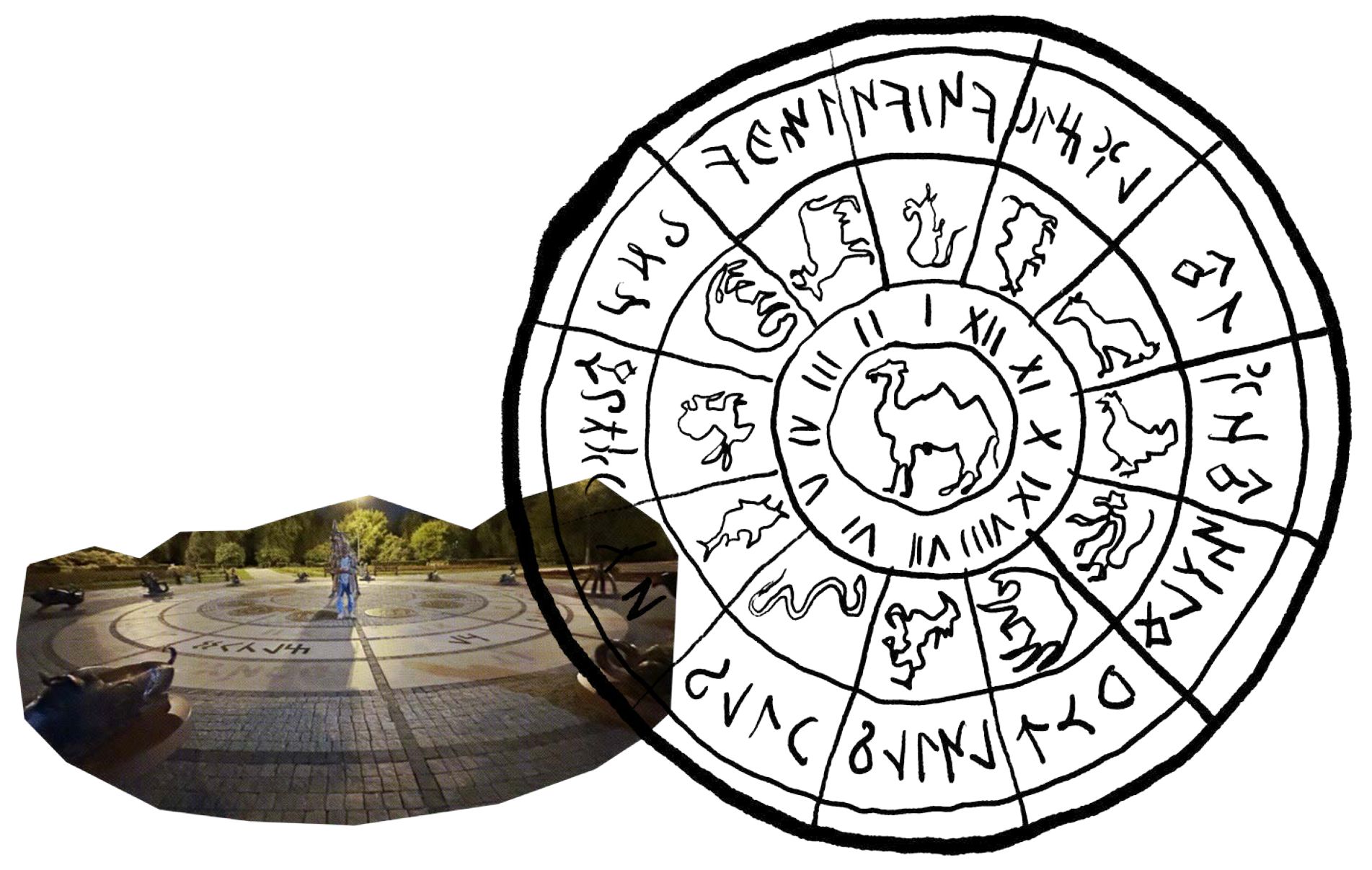

The sculpture at the front end of Gorky Park that seems to have been installed there just recently depicts animals of the Mushel calendar attributed to the ancient pagan cosmology in the region, and the related mythology—a camel is at the center with a mouse on top of its head, then in a circle around it are cow, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, ram, monkey, chicken, dog, and pig. The unique features of a particular animal are said to define the quality of a life cycle or the year it symbolizes. I felt that this sculpture, in its relation to the ancestral past is an apt juxtaposition to the present situation. To include it in the piece, I’ve amplified the sculptures and captured the resonant qualities of each animal. This element is also emphasized in the piece through the opening reading of the Kazakh fairy tale, “The Dispute of the Animals” whose creation is attributed to Ybrai Altynsarin, a well-regarded Kazakh pedagog and activist, prominent in the 19th century during the period of Russian colonization.

Fig. 22 Mushel calendar. Gorky Park, public sculpture. Mushel calendar is attributed to the Turkic cosmology in the region. Photographs are courtesy of the2vvo (2023); extracts of definitions and the illustration of the Mushel calendar sourced from Kairbekov, Bakhyt’s National Customs and Traditions: Kazakh Etiquette (2012); Fig 23 (small icon) Full circle. Almaty, Kazakhstan. Photographs and collage by the2vvo (2023)

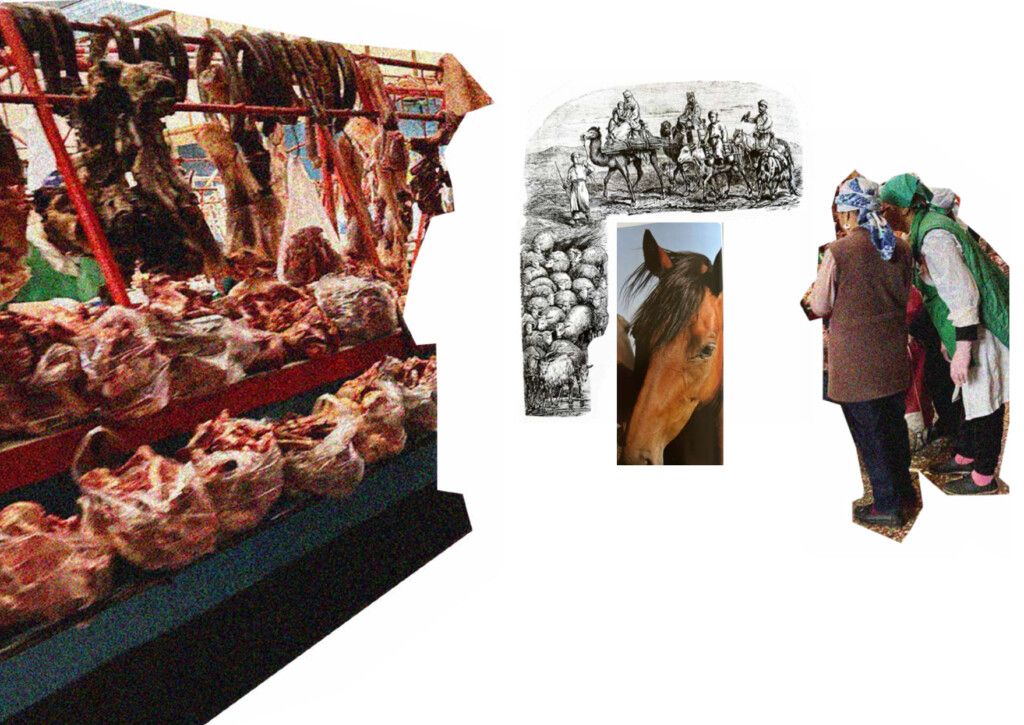

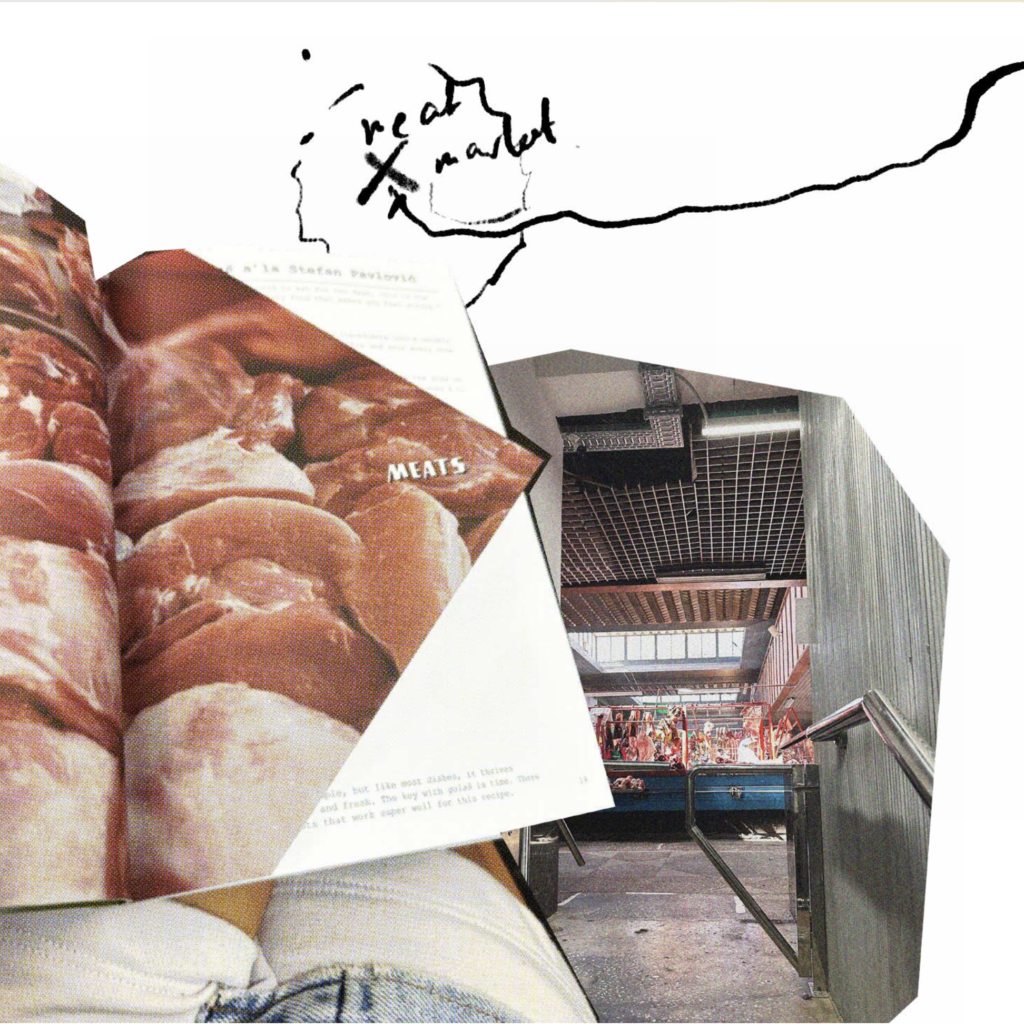

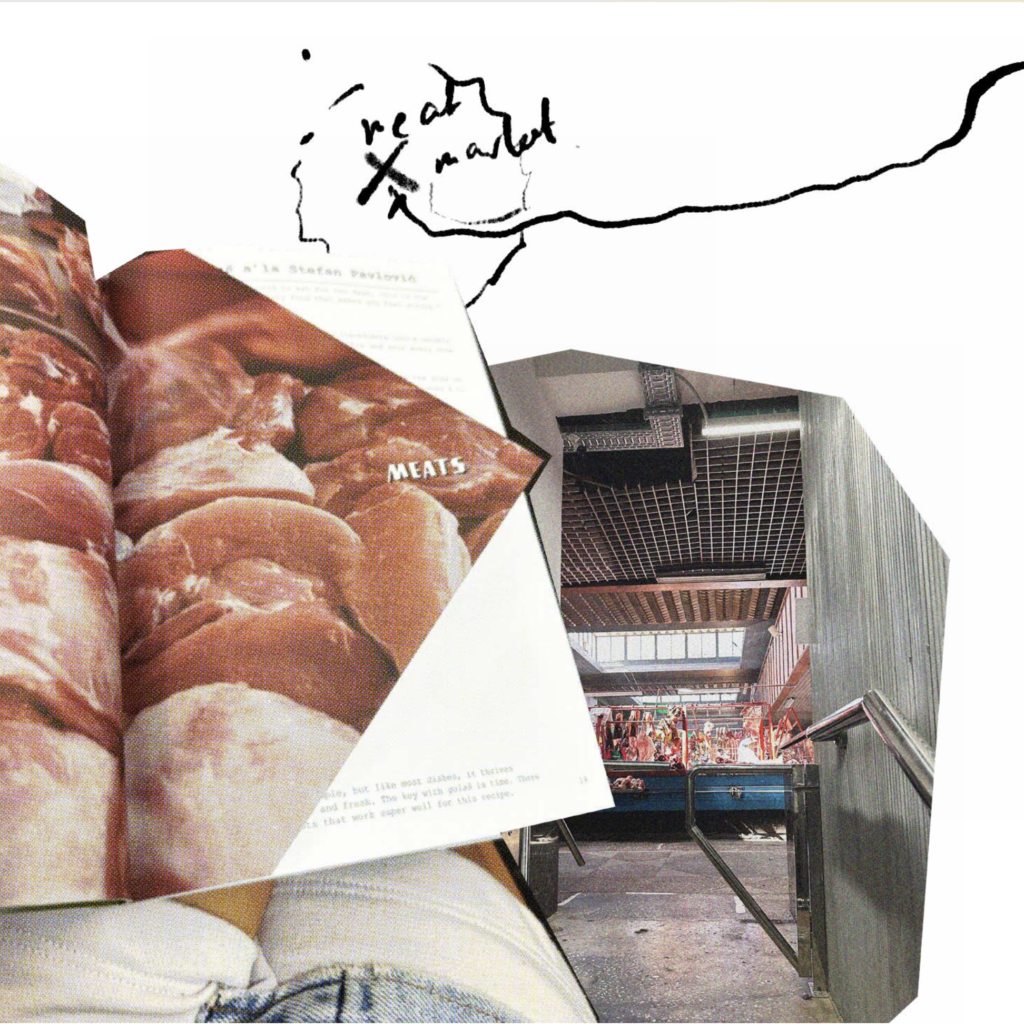

Further into the piece, the sounds of meat vendors and rhythmic chops symbolize human domination over animal bodies, accentuating our conditioned acceptance of this relationship. The introduction of the daxophone transforms the initial documentary premise into a surreal sonic ecoscape, blurring the lines between real animal sounds and improvised mimicry.

Fig. 24 Narrating the story. Collage composed with photographs made by the2vvo (2023)

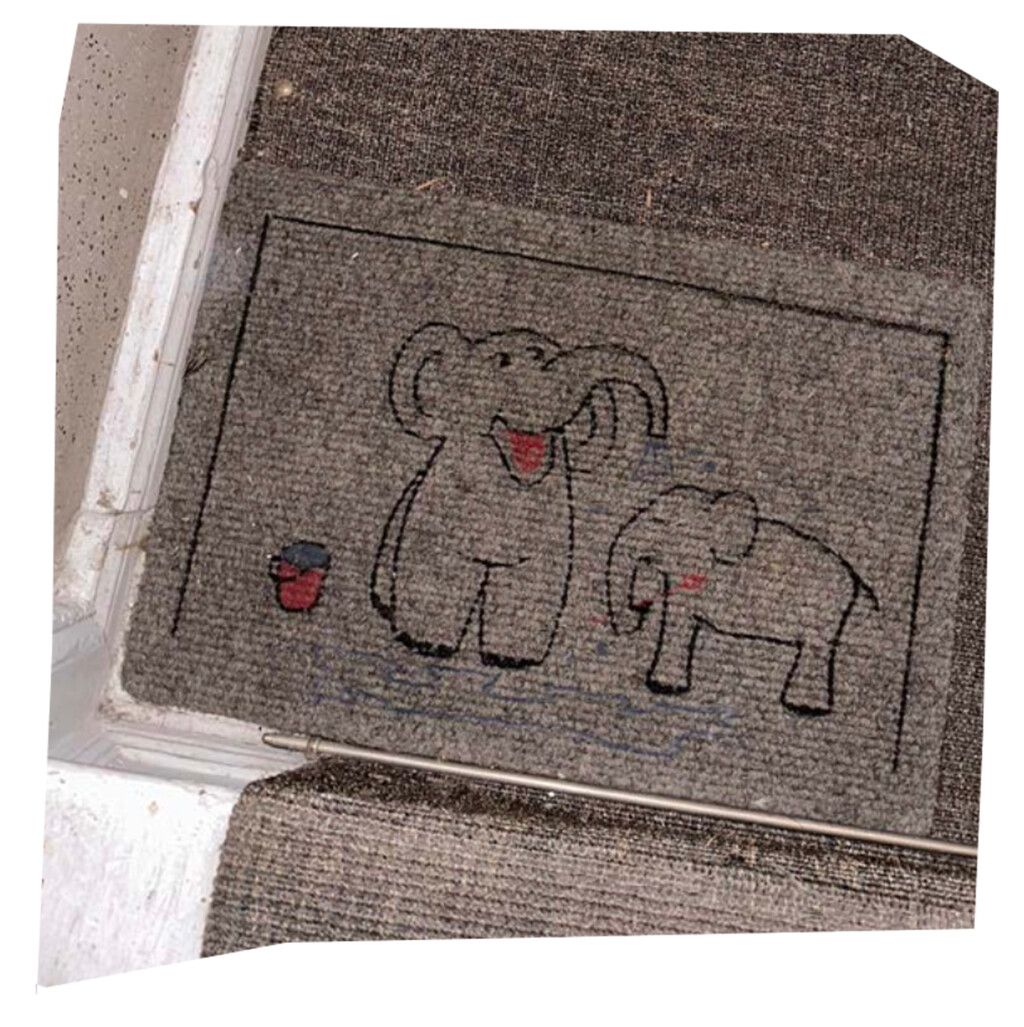

The piece concludes with a lightly processed found rendition of Marianne Moore’s poem “Black Earth,” which solidifies the project’s invitation to contemplate the liminality between human and animal experiences. From the viewpoint of an elephant, the poem provokes reflections on experience, self-awareness, exposure, vulnerability, power, resilience, and the quest for balance and centeredness.

“Elephant In The Room” is not merely a nostalgic reflection but a critical exploration of the evolving paradigms of human-animal relationships, aiming to ignite dialogues on the implications of our interactions with the animal world and to foster a reconsideration of traditions and norms that perpetuate violence and exploitation in contemporary societies.

Listen to the sound piece here.

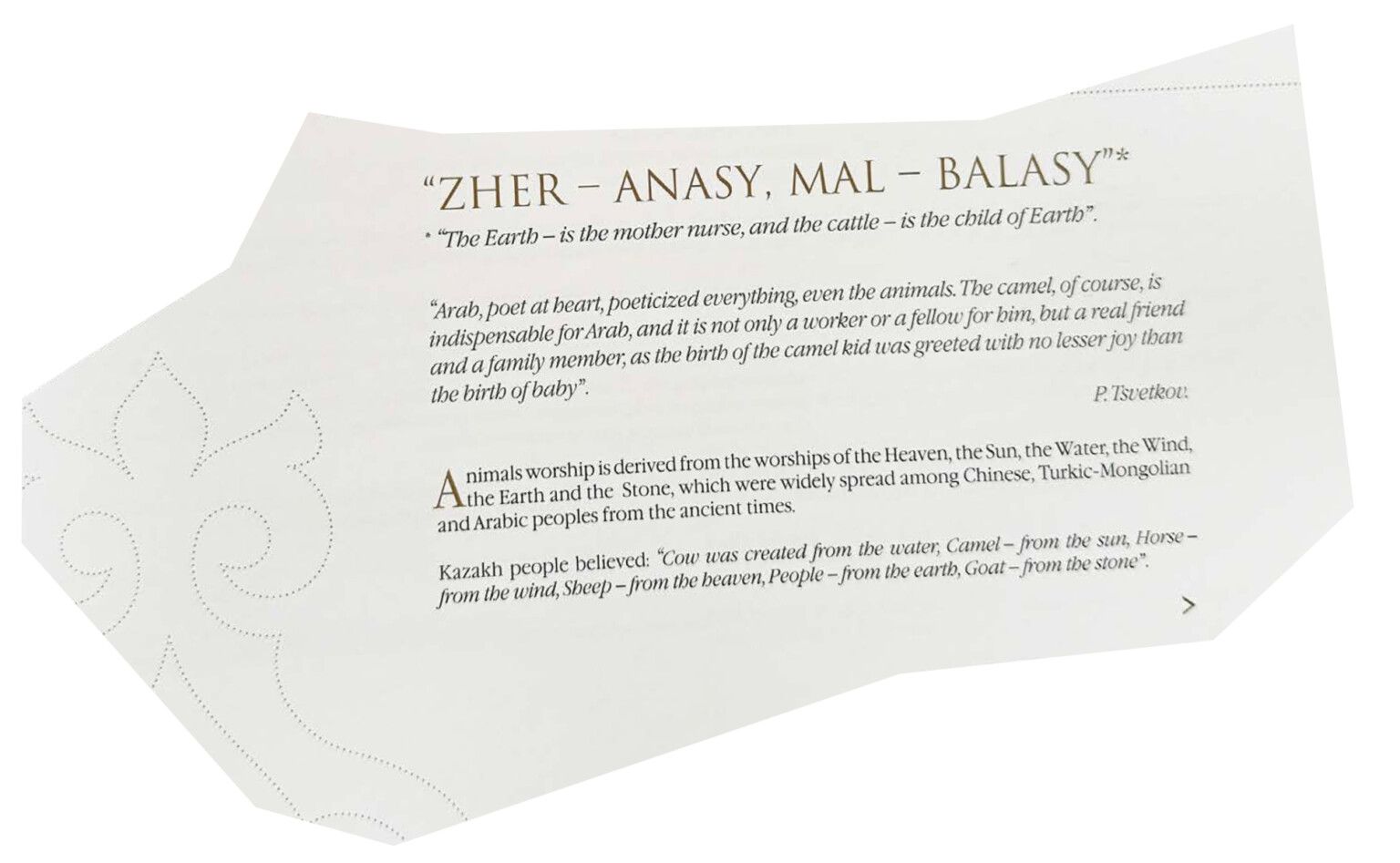

Fig. 25 Interdependence. Excerpt from Kairbekov, Bakhyt’s National Customs and Traditions: Kazakh Etiquette (2012); Fig. 26 Elephant in the room. Photograph made in Berlin. Image courtesy the2vvo (2023)

Works Cited

Aypov, N. G. “Tengrism As Open Worldview. Monograph / orig; Тенгрианство как открытое мировоззрение. Монография.” Kazakhstan National University of Pedagogy, 2012. Adams, C.J. and Donovan, J. eds. Animals and women: Feminist theoretical explorations. Duke University Press, 1995. Colin, Allen and Trestman, Michael. “‘Animal Consciousness,” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, n.d. <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2023/entries/consciousness-animal/>.

Kairbekov, Bakhyt Gafuovich. National Customs and Traditions: Kazakh Etiquette. Empire KZ, 2012. Ospanuly, Yerlan. “Mythological Images in Folklore of Kazakh People.” World Discovery Kazakhstan, January 2004. Ricard, Matthieu. A Plea for the Animals: The Moral, Philosophical, and Evolutionary Imperative to Treat All Beings with Compassion. Translated by Sherab Chödzin. First Paperback edition. Boulder: Shambhala, 2017. Rogozhinsky, A. “Time to Gather Stones: Archaeological Monuments of Tamgaly / Orig: Вермя Собирать Камини: Археологические Памятники Тамгалы.” World Discover Kazakhstan, October 2006. Rollin, Bernard E. “Animal Pain: What It Is and Why It Matters,” 2023. Samashev, Z. “Animal Style Art,” July 2006. Wyckoff, Jason. "Linking sexism and speciesism." Hypatia 29, no. 4 (2014): 721-737.

Eldar Tagi

Eldar (b.1987, Almaty, Kazakhstan) is a sound artist, composer and researcher.