There, There: soil

A change is taking place before our eyes that we ourselves are causing and yet we seem to be helpless in the face of it. The new living conditions brought about by the climate catastrophe leave us disoriented, according to French sociologist Bruno Latour. To counter this, he says, we need to become "terrestrial", to land anew on this changed earth that is once again unknown to us. We must understand that we do not live on earth but in the “critical zone,” the only zone that allows life, a zone that measures only a few kilometers. (Latour, 2020)

What does it mean to land in a place, to really ground yourself? And what would a place look like where we can really land? How do we regain contact with the ground we have lost under our feet?

A Place to Land on Earth is an ongoing research project, which takes on different forms in order to explore these questions. Here we can rehearse our landing, play through various scenarios and get back in touch with the earth – metaphorically and literally.

1. Soil

Soil, source: Insa Langhorst

Soil, source: Insa Langhorst

In the Anthropocene almost everything is geology. Human activity is founded in the soil, in the rock, whose ghosts are drifting in the atmosphere.

Our lives depend on soil. It feeds us, filters our drinking water, stores CO2. The composition of soil is a significant climate factor. Around 2,700 gigatons of carbon are currently stored in the soil - a huge amount when you consider that humans produce around nine gigatons of carbon a year. (Initiative Grund zum Leben, 2015) Soil creates, decomposes and harbors life.

But we have lost the ground under our feet. We are well on the way to destroying ourselves. If we carry on as we are, fertile soil will be gone in a few decades - and with it our bedrock of life.

Many residents of urban areas hardly ever get to see any natural soil, as most of it is built on and sealed - and therefore destroyed. In fact, more and more soil is being sealed. (Initiative Grund zum Leben, 2015) This also influences our thinking: as city dwellers. We usually associate soil with dirt. But what makes it dirty is what humans have added to it. The rubbish we leave behind, the damage we cause.

In the past 40 years, overgrazing, deforestation and unsustainable soil management have already rendered a third of the world's arable land unusable. 20-40% of soils are damaged. Overall, the existence of at least 1.5 billion people is at risk due to land and soil degradation. Regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and South America are particularly affected. (Initiative Grund zum Leben, 2015) We have to understand that soil not only nourishes, but also needs to be nourished. Soil is not infinite and although it is a renewable resource, its growth is so slow that it is almost irrelevant to us. What is soil? What is it made of? How does it grow?

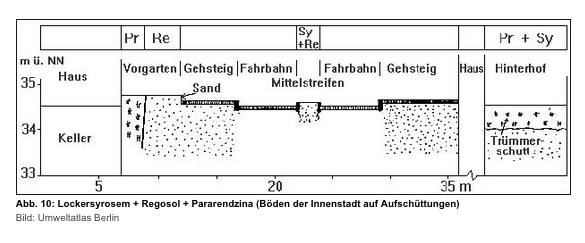

There are different kinds of soil: terrestrial soils (the most common), semi-terrestrial soils, semi-subhydric and subhydric soils, as well as bogs. An even finer subdivision describes subtypes in order to distinguish special characteristics of the 56 existing soil types. (Umwelt Bundesamt, 2018)

Mountains are the “parents of soil”, the geological material from which soil is generated. Soil is formed by the weathering of rock and the crushing of mineral particles, often at an atomic level. (Banwart, 2020) But soil is more than this. Decomposed organic components (the humus), mineral particles interspersed with water and air as well as a multitude of plant and animal life form the soil. And as such, soil is the living skin of our earth.

Soil is full of life. Several million fungi and bacteria live in one gram of soil and most of them - over 90% - are unknown to us. A teeming universe, created over thousands of years. More organisms live in a handful of soil than there are people on earth. They all contribute to the fertility of our soil by loosening, aerating, mixing, fertilizing and stabilizing its structure. Without this fertile soil, which stores nutrients, water and carbon, the diversity of species on our planet would quickly dwindle and our food supply would no longer be secure. (Initiative Grund zum Leben, 2015)

Exhibition view A Place to Land on Earth, source: Insa Langhorst

This mixture is slow to develop. A one-centimeter-thick layer of soil might need 100 to 300 years to build up – and it only takes one heavy downpour to wash it all away. Soil is an heirloom, a long-term investment that requires foresight and patience. And this is notoriously not a human strength.

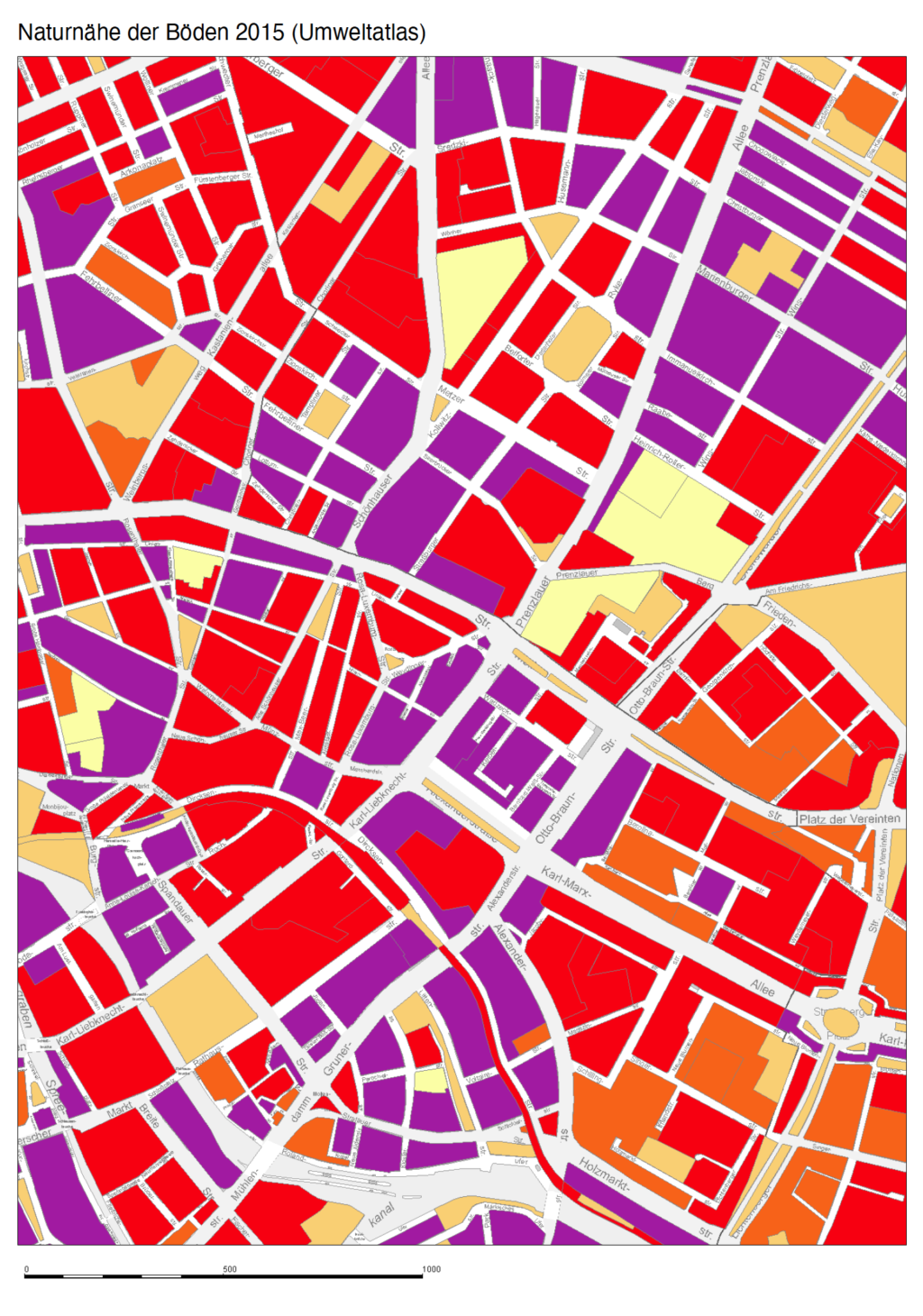

The urban climate heats up due to sealed surfaces because buildings and asphalted roads store heat. (Initiative Grund zum Leben, 2015) Unsealed surfaces help the city to cool down at night and prevent it from heating up during the day. Noah Webster, who compiled the first dictionary of American English, was already concerned about the increasing heat in cities and its impact on health in 1800. He advocated the use of trees along paths and roadsides as natural sources of shade and cooling. (Rankovic, 2020) Green spaces are synonymous with recreation. They are counted as an indicator of environmental justice, according to which everyone should have access to an adequate supply of green spaces. In Berlin, for example, 48% of residents have good access to green spaces, while 29% have poor access or no access at all. Yet, studies show: A good supply of green space is possible even with a high population density – it is all a question of planning and priorities. (Unweltatlas Berlin, n.d.)

When a new tree is planted in Paris, the old soil is completely replaced. It is assumed that the previous tree has "used up" the soil. This hypothesis has never been tested, but persists in thought. Once a tree and its soil have been planted, it is left to develop its own resources - in the midst of stone and concrete. There is no additional watering, foliage is removed. This means that no new nutrients, no humus, can be created. It is not surprising that people think trees use up the earth's resources. They have no other choice. (Rankovic, 2020)

Ground horizon of urban streets; source: Umweltatlas, https://www.berlin.de/umweltatlas/boden/bodengesellschaften/2015/kartenbeschreibung/

2. Becoming Terrestrial

When we care about the soil, we automatically form a bond with it. But the return to the soil, the foundation of our lives, is uncomfortable for many. It seems too reminiscent of the blood-and-soil thinking of the Nazis. Critical Zonists, on the other hand, see soil as something very different from the Nazis. They do not see it as a homogeneous space belonging to one species, but as a patchy, heterogeneous, discontinuous composition. A composition. (Latour & Weibel, 2020). It should be possible and must be made possible to feel a sense of belonging to a soil without confusing it with the demands of localism (ethnic homogeneity, historicism, nostalgia and false authenticity).

What do you mean when you say a land is your land? “How many partners do you include in the production of it? How thick do you calculate it has to be? 30 centimeters? 3 meters? 3 kilometers? What about the way water circulates through it all the way down to the deep rock beneath? Have you thought about its porosity and granularity? Are you sure you did not forget earthworms? When you say it”s “yours”, do you include the red sand blowing from the Sahara or the acid rain from Chinese factories?”

(Latour & Weibel, 2020)

Bruno Latour was of the opinion that we have not yet really landed on earth. According to him, one of the main problems relating to this was a misunderstanding of the concept of "nature". As an antidote he brought the concept of "becoming terrestrial" into play. (Nilo, 2023)

“Terrestrial [təˈres.tri.əl]

The term »terrestrial« tries to capture the general trend toward the Earth that has marked the beginning of the twenty-first century. Political ecology tried to interest people in the fate of »nature«. But »nature«, by definition, is exterior to society and doesn’t enter easily into a political agenda. Another word is necessary to target the goal of landing somewhere after a few centuries of emancipation away from the Earth, toward the infinity of progress. But for the beings who live on it, Earth is not a planet viewed from out in infinite space, as one celestial body among all the others. It is much too specific, much too unique, and it is also much more material and »earthly«. The strange thing is that all industrial societies are discovering at the same time that they know very little about the fragile and restricted conditions of the habitability of the Earth. »Terrestrial« is the name of their surprise and anxiety.”

(Latour, n.d.)

To really counter climate change, we need to reshape our material relationship with the earth. We need to rethink categories. Globalization, the flight forward, and localism, the flight back, are both impossible utopias, divorced from the material reality in which we live. Latour saw the terrestrial as a new political actor. The new politics that emerges with and through this concept must enter into a dialog with the earth. He proposed that we no longer speak of humans, but of terrestrials, the earthbound, in order to bring out the humus, the compost, which is in the etymology of the term "human". By seeing ourselves as humus, we can connect more strongly with the earth. (Nilo, 2023)

The oldest task in the history of mankind, said ecologist Aldo Leopold, is to live on a piece of land without destroying it.

Map of Berlin-Mitte and its degree of de-naturalisation; source: Umweltatlas

“We abuse land because we see it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect. We shall never achieve harmony with land, any more than we shall achieve justice or liberty for people. In these higher aspirations the important thing is not to achieve, but to strive. … The problem, then, is how to bring about a striving for harmony with land among a people many of whom have forgotten there is any such thing as land, among whom education and culture have become almost synonymous with landlessness. This is the problem of 'conservation education'. Conservation is not merely a thing to be enshrined in outdoor museums, but a way of living on land.“

(Leopold, 1949

A terrestrial view involves recognizing that humans are not the only actors in our world. Terrestrials are much more: beings and things that have some form of coherent identity and influence events can be called terrestrial. This includes not only vegetables, but also clean air and insurance networks, for example. The result is a vision that is simultaneously local and global, but above all irretrievably interconnected and material. It is a rich model of democracy that includes many forms of being. Although it is a way of thinking that is connected to the earth, it is also worldly in the sense that it does not rely on boundaries and points beyond all identities. And according to Bruno Latour, we do not live in a world of things, but in a world of forces and their effects. (Nilo, 2023) We are not beings distinct from nature. Our dominance is an illusion.

Towards the end of his life, Rousseau attempted to re-explore the social through the mediation of botany. His project of reintegrating the "energy" of the living into the social was not focused on human institutions such as the church, but on the forest. By turning his back on society, he tried to change it. (Laplantine, 2015)

3. New Definitions

What happens when the concepts we have used so far no longer fit? When we say nature but don't mean it, or nature doesn't feel it is meant? If we no longer have words to name things, do they remain part of our thinking? If we cannot feel things, how can we communicate concepts?

I remember a passage in an article I read describing an encounter between a blind person and a spider. The fragility of the spider, its speed, makes it almost impossible for the blind person to experience it. (Everett & Gilbert, 1992) What does our sensory limitation mean when it comes to experiencing the world around us? Especially when we compartmentalize our senses, treating them as individual entities instead of thinking of them together?

In order to really address climate change, we need to get back into a material relationship with the earth. We need to rethink the categories we use. This includes concepts such as politics, nature, the global and the local. (Front Porch Republic, 2019) According to Bronislaw Szerszynski we need to dig deep into the “archives of our language”, because there have been changes there that make it more difficult to talk about actions in the critical zone. If we find the right words, we can act. (Szerszynski, 2020) If we tell new stories, positive science fiction, then these stories can become reality. The same applies to negative future scenarios. We have history in our hands, so to speak, and under our feet.

The terrestrial vision teaches us to think things together. Soil is another such construct that only makes sense in connection with the processes in which it is embedded.(Krzywoszynska, 2020) Only through exchange and connection does it become a living part of the "critical zone".

“If we act on the words of Aldo Leopold and "think like a mountain, " we see soil as a living being with which to build a relationship. if we treat soil well and gain its trust, humans and soil can domesticate each other and build a productive partnership to weather the perfect storm. Humans need soil to act well if we are to reach 2050 and still feed the world, provide clean water, support global biodiversity, and prevent harmful effects of climate change. If we continue to treat soil badly, it will continue to react badly, to pull back and kick, a difficult action for humans to manage while navigating a raging storm.”

(Banwart, 2020)

4. Finding the Body

The body, with all its sensuality, is the foundation of existence. What happens if it is not grounded?

“When people still walked barefoot, changing surfaces - soft and cool, stony and spherical or pointed, rough and rubbed - provided the stimuli for the soles, which can contribute to maintaining the health of the organs corresponding to the zones touched on the foot. After all, 72,000 nerve cells converge on the feet and their signals have a decisive influence on physical well-being.”

(Fuchs, 2002)

As well as the sole touching the ground, the laying on of hands has also always been considered powerful and healing.

“It is not necessary to go back to the Egyptians in 2300 BC or to Greek and Roman bathing culture - everyone knows that a mother's hands are the best help for a sick child, affecting both body and soul. [...] Perhaps this is the origin of massage practices. After an eventful history and at times complete oblivion, massage was re-imported to Western Europe as a healing body therapy by Bonaparte's armies from the Egyptian campaigns at the end of the 18th century: From Turkish baths, they brought back a form of treatment that was completely unknown to them, which they called 'massement'.”

(Fuchs, 2002)

Reflexology map of the feet; source: drawn and colourized by Jimmy - enWiki, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1210174

Let's use our bodies, our senses, to land on Earth, in the critical zone, the only habitable area of our planet. To really land. We need to start thinking terrestrially: a world in which the small contains the large and the large contains the small, in which what is whole and what is part is questioned. We are not extra-terrestrial, we are terrestrial beings. (Latour & Weibel, 2020)

Let's (voluntarily) give up the vertical in favour of the horizontal for a moment, as the philosopher Wilhelm Schmid suggested. (Schmid, 2019)

1. lie on the floor, so that you touch it with your whole body; lie on your back, your stomach, sideways, stretched out, curled up.

The muscles gratefully accept the break in the fight against gravity. Feeling the ground also reduces the fear of falling. There is always a ground that supports you, even in the abyss. You cannot fall any lower.

2.breathe deeply

Lying down voluntarily is a contrasting experience to rushing through the world upright. From a position of rest, we can regain our footing. Looking up from below instead of down from above fundamentally changes our perspective. Touching the ground makes us more open and creative. The exercise of touching the ground, which leads to deep breathing, also deepens our understanding of connections. With every breath we take, we touch the atmosphere and are touched by it. The body penetrates the planet, the planet penetrates the body. Touch, as our most direct, least intellectualized sense, is the grounding sense, the sense that locates us in the world. (Kemske, 2009)

The ground beneath our feet, the sand that runs from the palm of our hand through our fingers, the twigs that brush against our arms, the grass on the skin of our legs, the wind in our hair. We have far too little contact with the world around us. Even children today hardly have the opportunity to experience the world around them with their hands and feet, to "go from feeling to emotion."(Fuchs, 2001) Richard Louv described the loss of contact with nature as a "nature deficit order" (2005), the symptoms of which are reduced use of the senses, attention problems, and higher rates of physical and mental illness. The positive effects of being in contact with nature are manifold. More experience of nature also leads to more social connections. Children who grow up close to nature have higher self-esteem. Gardening is used as a tool to treat chronic illnesses such as depression. (Steinwald et al., 2014)

Exhibition view A Place to Land on Earth, source: Insa Langhorst

5. A Place to Land on Earth

We need more contact with the ground, horizontal moments, space for thought. I remember that even ten years ago, there were far more open spaces in Berlin. Spaces that opened up possibilities and allowed for experiments. Space to land. Space that you could get involved with because it got involved with you. How do we find it, the place where we can land on earth?

[T]here is another wave of shock that goes beyond the 19th century trauma that ‘I don’t know what a machine is and what a human is.’ One step further is: ‘I can feel my own extinction, I have produced my own death’. If the white wall was an integral part of the defensive reaction against the fears of the 19th century that continued to be radicalised in the 20th century in such an immersive sea of white that the white no longer even has to be there to be there, it is possible that a new thought emerges out of the problems faced today in belated reaction to the perception of the whole planet as a doomed work of art.”

(Wigley, 2016)

Works Cited

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanach, New York 1949.

Aleksandar Rankovic, Exploring Trees, Soils and Microbes in the Streets of Paris, in: Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (eds), Critical Zones: the science and politics of landing on earth, Karlsruhe 2020, p. 150-153.

Anna Krzywoszynska, Soil Care Network: Caring for Soil as Building Relations, in: Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (eds), Critical Zones: the science and politics of landing on earth, Karlsruhe 2020, p. 372-373.

Bonnie Kemske, Embracing Sculptural Ceramics: A Lived Experience of Touch in Art, The Senses and Society, 4:3, 2009, p. 323-345, https://doi.org/10.2752/174589209X12464528171932.

Bronislaw Szerszynski, The Grammar of Action in the Critical Zone, in: Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (eds), Critical Zones: the science and politics of landing on earth, Karlsruhe 2020, p. 344-348.

Bruno Latour, On Critical Zones, 2020a, https://zkm.de/en/zkm.de/en/ausstellung/2020/05/critical-zones/bruno-latour-on-critical-zones.

Bruno Latour, “Terrestrial”, in: Glossolalia: Tidings from Terrestrial Tongues, 2020b, https://zkm.de/de/glossolalia-tidings-from-terrestrial-tongues.

Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, Seven Objections Against Landing on Earth, in: ibd. (eds), Critical Zones: the science and politics of landing on earth, Karlsruhe 2020, p. 14 -18.

François Laplantine, The Life of the Senses. Introduction to a Modal Anthropology, London 2015, p. 61f.

Initiative Grund zum Leben, Themendossier Boden, Bonn 2015.

Johannes Nilo, “Landing on Earth”, 05.05.2023, https://dasgoetheanum.com/en/landing-on-earth/.

John Everett and Wally Gilbert, “Art and touch: a conceptual approach”, in: The British Journal of Visual Impairment, Volume 9 Number 3, 1992, p. 87-89.

Mark Wigley, Discursive versus Immersive: The Museum is the Massage, Stedelijk Studies Journal 4 (2016), retrieved on: https://stedelijkstudies.com/journal/discursive-versus-immersive-museum-massage/.

Melissa Sexton, “Rethinking the Local vs. Global Divide”, 18.02.2019, https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/2019/02/rethinking-the-local-vs-global-divide/.

Molly Steinwald, Melissa A. Harding, and Richard V. Piacentini, Multisensory Engagement with Real Nature Relevant to Real Life, in: Nina Levent and Alvaro Pascual-Leone (eds), The Multisensory Museum. Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space, Lanham 2014, p. 45-60.

Steve Banwart, Domesticating Soil in Earth's Critical Zone, in: Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (eds), Critical Zones: the science and politics of landing on earth, Karlsruhe 2020, p. 90-93.

Umweltatlas, 2020, https://www.berlin.de/umweltatlas/nutzung/oeffentliche-gruenanlagen/2020/einleitung/.

Umweltbundesamt, Boden, https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/boden-flaeche/kleine-bodenkunde/bodentypen.

Ursel Fuchs, Leben mit Wachen Sinnen. Damit uns nicht Hören und Sehen vergeht, Düsseldorf 2001.

Wilhelm Schmid, Von der Kraft der Berührung, Insel Verlag 2019, p. 29-35.

Insa Langhorst

Insa is a freelance curator and artist with a background in ethnology and cultural education. She completed an MA in Visual Anthropology at the University of Manchester.