0:0:0.0 --> 0:0:0.470

Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) We’re two.

0:0:0.0 --> 0:0:0.470

Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) We’re two.

0:0:2.580 --> 0:0:4.290

María Angélica Madero We are The Colonial Remediators. Hmm. The transcript is saying “The Colonial Remediators”, not Decolonial Remediators.

0:0:24.820 --> 0:0:30.380

Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) It's not part of the AI Dictionary. Not suspicious at all.

0:0:36.440 --> 0:0:42.440 María Angélica Madero It's already translating our dialogue. It’s a transcript.

0:0:51.460 --> 0:0:52.50 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) Sub.

0:0:56.920 --> 0:0:58.420 María Angélica Madero Sub translating.

0:1:10.260 --> 0:1:13.50 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) It doesn't translate laughs into Spanish either.

0:1:14.310 --> 0:1:15.620 María Angélica Madero

0:1:20.130 --> 0:1:24.510 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) So we are the Decolonial Remediators. In a way, we're just gonna tell the story of our project. And how we went from expectations to reality. And the different changes that we've been through, the discoveries we didn't expect, and where we are now.

0:2:1.660 --> 0:2:5.430 María Angélica Madero I think the story starts with Sofia Vergara. When she says:

This was a starting point and also an endpoint. Because in a way, the project overall had to do with walking: in putting someone else's shoes as a method. The project’s aim wasn’t to create a finished translation, but it had to do with the act of translating itself. And that's why trying to walk—or talk—in someone else's shoes for one mile is in frequency to what we desired to do.

0:3:35.710 --> 0:3:37.890 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) I think about the shoes you and I walk in every day, translating ourselves into a different context, translating our experience, our situated knowledge. Always translating inside our heads, as we are now, having to communicate in English, so what we say can be recognized by the AI transcript. In some way or other we both clicked with the subject because it's something that's a part of our everyday and of our memory. We’re constantly having to deal with translation.

0:4:57.320 --> 0:5:4.870 María Angélica Madero Not only in the “situated knowledge,” as you call it, but also as part of our teaching practice. We try to emancipate texts and their meaning in class, by opening up what is written in the page. Let’s also acknowledge that this has several implications in relation to misunderstanding, mistakes, and giving up. We could claim it is a sort of expansion of meaning that paradoxically limits understanding (or maybe it doesn’t). We give up a meaning while we construct a new one.

And this reminds me of a conversation we had many, many, many, many years ago—maybe 10 years ago in Bogota—where we agreed that we don’t care about the meaning of words, but about the sense that they produce. To some extent when one is translating one is not actually imitating an original, but there’s always an interpretation. There's always a copy, like a fake. Going back to earlier, this relates to errors, misunderstandings, mistakes, as well as the “non-original”, the impure. You said it once, intoxicated.

0:7:10.780 --> 0:7:18.60 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) You mention emancipating the text at the beginning. Today by chance I ran into a quote by Simon Rodriguez, the tutor and mentor of Simon Bolivar. He says “To read is to resuscitate ideas buried in paper. Each word is an epitaph.” We have a deep relationship to this in terms of knowledge, of otherness and of language, as well as our relationship to the world from the place where we come from, watching the things we grew up watching…

0:10:3.960 --> 0:10:11.310 María Angélica Madero I love Simon Rodriguez’s quote and the idea that to read is to unbury. This reminds me of that time we talked about unearthing. I associate it with intersemiotic translation1, and more specifically, translating text into gestures. Remember we wanted to do an undertranslation and bury the resulting text in a garden? That was the time we acknowledged collectivity, as we realized translating text into gestures was a sort of opening into our everyday life, as you say. But not only you and me, but everyone, as it primed collective meaning—or better, sense-making—which became central when we started to work with others.

0:7:10.780 --> 0:7:18.60 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago)

Well, the title of the project anticipates that in a way. Decolonial Remediators comes from an interest in decolonial theory, and in translating decolonial theory that only exists in Spanish, into English or other languages, or to translate theory into Spanish. The aim to circulate knowledges2 that do not circulate so much. We started by making a list of texts to be translated, identifying different materials, those we thought were especially urgent to translate. That first impulse explains the “decolonial”. The “remediators” was a pun. It's a funny word, because in Spanish it is something a bit naughty. “Arremedar” is something you shouldn't do, that you are told not to do in school or by your mother, it is the act of imitating or to copy others. But then in English it has a different meaning: it is to provide a remedy, to make something right. This word that generates misunderstandings actually fits into the project, representing its spirit.

0:10:3.960 --> 0:10:11.310 María Angélica Madero

At that time I was also very obsessed with psychoanalysis and the idea that every language has its own unconscious in our heads. That means for me that we speak in a multiplicity of voices. This lead us to think about the voice and who speaks, who dominates the space of the visible and the audible, what Jacques Rancière describes as the distribution of the sensible. As we wanted to make different voices visible and audible in different languages, we discussed in depth Gayatri Spivak’s idea that says something like the question is not why the subaltern is not speaking, but why we’re not listening to them.

0:7:10.780 --> 0:7:18.60 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago)

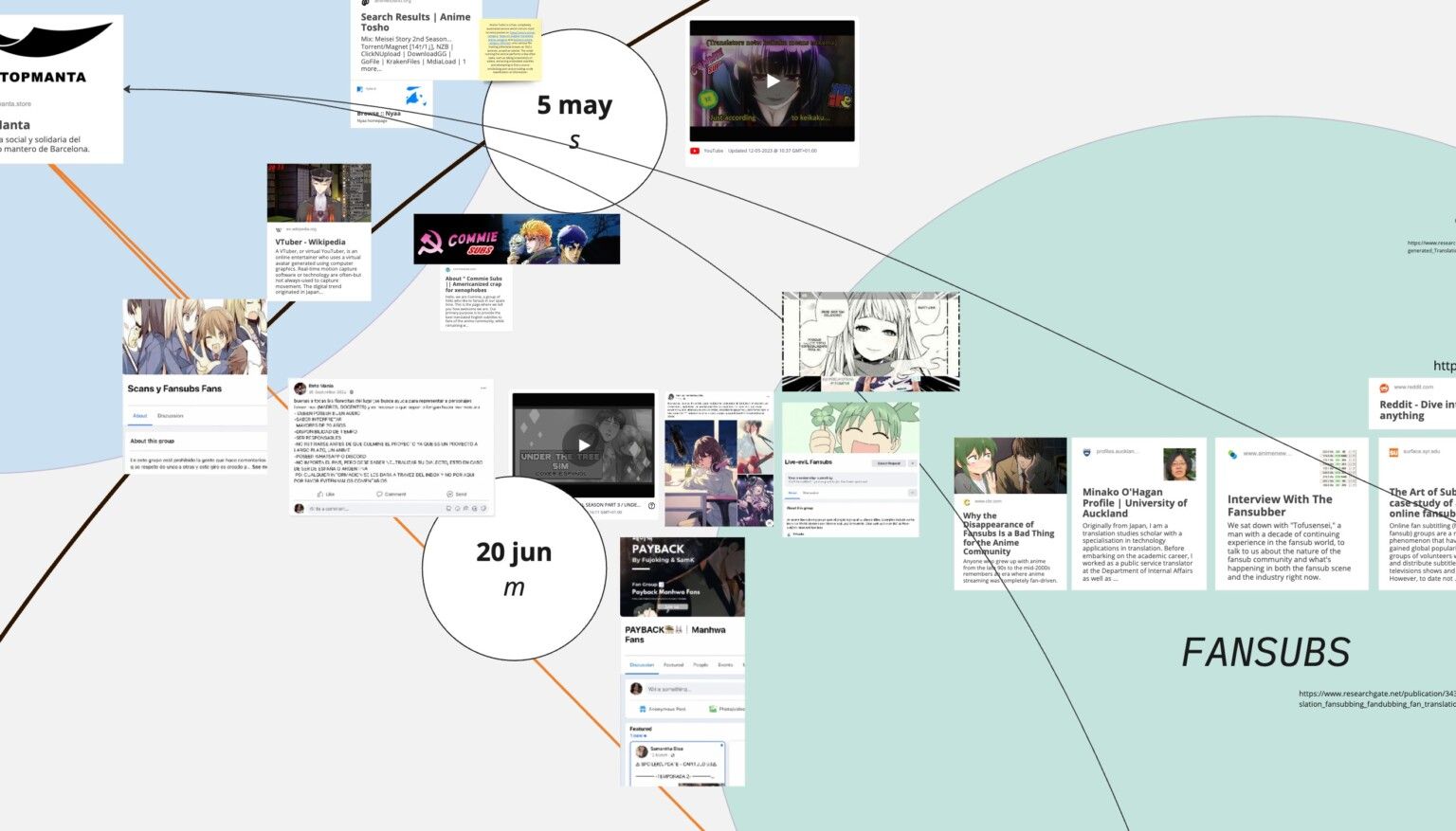

Maybe our method is not only a method of translation, but a method of listening. Our proposal said that we were thinking of translation as a method and radical practice of sharing which is political. Our thesis was that there’s an unequal access and distribution of knowledge and translation is a way to act on those geopolitical forces. But we saw this happening in non-art contexts. In trying to find ways of doing this, we made some netnographies3 looking at how fansubs4 worked, for example.

0:10:3.960 --> 0:10:11.310 María Angélica Madero To expand a little bit, fansubs are online communities interested in Japanese Manga who collectively translate new films. And they distribute them for free even before the original translation is out there. So it is a very radical way of distributing, giving people something which is “coming”. An anticipation. So to reinforce what you said, we're interested in ideas of distributed authorship and collective sense-making, as it happens in fansubs. Everyone that takes part becomes central, as each person holds a fragment that is part of a bigger whole, and the act of sharing is what creates understanding.

So if we were to describe the method, I’d say that whenever we describe it, we find new ways of applying it. For me personally the method starts when there’s a group of people sitting together. It runs from warming off with a game (any game) to later be subsumed by an intense silence, as everyone sits and translates a fragment of a text. We usually end the session with everyone describing what they did, what they had to unbury, what they had to open, or to unearth. And that sharing produces a new text.

0:12:33.560 --> 0:12:35.790 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) Following that, the incredible thing about the method is how it became an event, and how materiality and experience became central. So the true treasures of the method happened in the most unassuming way. When we were together and considering the minor details of the experience. We originally had many expectations about accomplishing this project as a digital platform. Something that could have that scale and outreach. In those delusions of greatness we even talked about having legal assistance from the school of commons. (laughs)

Maybe to show this better and how we materialized the project we could give some glimpses of the workshop in Zurich. Many of the choices we made then, became gestures that we've repeated in one way or another.

0:15:10.600 --> 0:15:25.880 María Angélica Madero What happened in Zurich was that we wanted to start with the body, so everyone using dry clay had to shape their own pens. There was a meta reflection about the tools for translation, as you mentioned.

008

We were interested in that confluence—or impurity—of different voices coming together. So in Zurich, what happened was that those multiple voices—or multiple impulses—of diverse readings became visible.

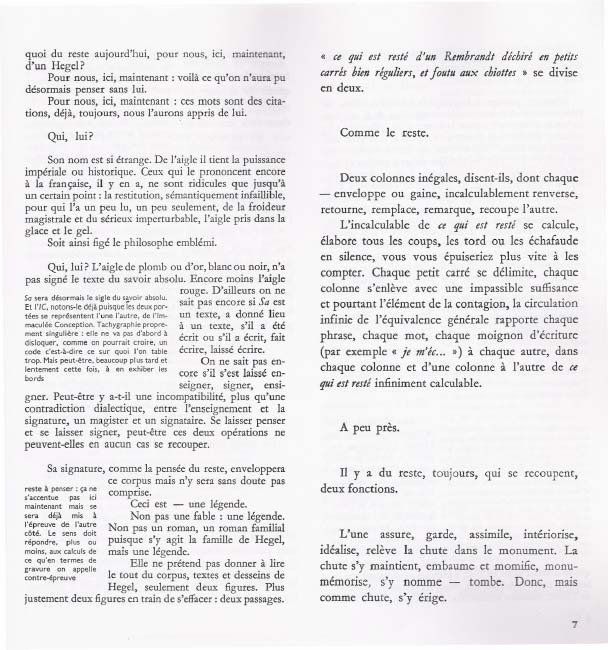

0:17:20.900 --> 0:17:36.720 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) When we were thinking about what text to translate we ended up choosing Barranquilla 2132 by José Antonio Osorio Lizarazo, a colombian science fiction book first published in 1932. Colombian science fiction already is a very strange object, as there's not much science fiction produced in Colombia that I am aware of, and this is why we chose it too. In a way, we liked it because it wasn't a straightforward decolonial theory and it wasn't academic knowledge. Nevertheless, it contained many of the claims of decoloniality. It presents theory not in a non metaphorical way. And then it also happens that we both have a relationship with Barranquilla, a city in the Caribbean. So there was also an emotional link to this place for both of us when we decided on this book.

On previous occasions we had a scanned copy that we translated on the margins using the difference of size between the original size of the book and the format of the paper where it was printed. But on this occasion we took the book apart, as María Angélica had a copy of the book. We unbounded it, and we attached to each of the pages an extension. So the book became unbounded and expanded at the same time. There was a powerful semiotic translation in this gesture, as a book is not meant to be unbounded, broken apart. And then it becomes redistributed among a group of people. We gave everybody one or two pages. In a way we added a third space, a third column we were very interested in.

0:20:22.870 --> 0:20:42.440 María Angélica Madero You mentioned earlier our netnography, where we tried to unearth some of the dynamics in these groups. There were also a lot of aesthetic decisions in the things these communities did. For example, they didn’t standardize the subtitles. Subtitles were made evident by disrupting the image. We also found that these communities have stopped nowadays, there's not a lot of active Fansubs communities. I think AI has had an impact on translation. And there's questions that are unresolved for us still.

0:23:45.950 --> 0:23:46.620 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago)

And paradoxically, since we are using it right now, the technology of speech recognition and AI translations are becoming faster and faster. Before Fansubs were faster than official translations, but now official translations are almost immediate. The fansubs that are still active are because they bring the insider perspective, the amateur, they have a relationship with what is being translated. They understand the story and bring a lot of comments and annotations into certain words and expressions, and even keep some words in the original language which is something important for a manga followers: not to translate everything.

Taking the example of fansubs, when we did the workshop we tried to do a translation with a large amount of people. For this we set up a long table, an exercise of commensality. In the table we distributed the text, each person receiving one section of the book. No one had read the book besides us, so no one had the complete picture of the story, only their fragment. So you could find out what was happening in the plot from the person that was next to you on either side. Some decided to talk but some decided to remain silent and listen to the playlist that María Angélica had made5.

0:27:24.430 --> 0:27:36.380 María Angélica Madero This makes me think about the relationship between translation, digestion and dreaming. The way in which one processes something, some piece of information. Something is “consumed” and generates a hallucinatory output. For example, dreaming, where there's a processing of information that is counterintuitive, completely unexpected.

0:23:45.950 --> 0:23:46.620 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) The instructions were very simple. We talked a little bit about interlingual and intralingual translations. Interlingual between languages, from Spanish to to English or to whatever language you wanted. And then intralingual is to put it on your own words, that could be slang, could be changing even the text to bring your own examples and to bring yourself into it. And not everybody had to translate into the same language.

We also didn't give much instruction on how to use technology if you wanted to. If you want to, you could use it as a support tool. It is there, but not to use it too much, you can also just use it once to get a grasp of what the text is about and then continue from there. From these very open instructions there were very different results.

0:27:24.430 --> 0:27:36.380 María Angélica Madero

That night after the workshop we ended up dancing bachata, salsa and merengue in Zurich, in Colmadon Bar with fellow latin american diaspora.

As we delved into translation, we ended up trying to condensate the method into a “Manifesto for Undertranslation” [see Appendix 1 and 2]. I guess it was because manifestos relate to instructions. And the way that we wanted to do it was also to open metaphorically ideas around undertranslating. This is why the manifesto’s first command is “Undertranslation es ir hasta abajo, a fuego, es playing reggeaton a las 2 de la mañana in a stoic bachata dancefloor”. So there's already no constraints to the way in which we want people to read, interpret and engage with the text. We want to emancipate the text. This connects with the ideas around decoloniality that you mentioned earlier.

0:30:29.850 --> 0:30:48.60 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) The manifesto became a way for us to reflect on the experience of being in Zurich together. On observations, insights, anecdotes. In that way it's still ongoing, always growing with new experiences. Always undertranslated. It's also a homage to the Ultratranslation manifesto by the antenna Collective6, which is also an important reference for us.

Thinking about reflection I also remember how in the workshop in the end everybody shared something about what and how they had translated. In a way we managed to read the whole book. To read it together, was another element we hadn't fully considered beforehand. It was an important and unexpected finding. Bounding the book back, by spoken word.

Finally we bundled up the book together in its original form and sequence. Made an improvised exhibition of the different pens shaped by everybody on the ledge of a window to let them dry. It was a nice moment of closure seeing all of them together, looking at the different shapes and traces.

0:33:2.140 --> 0:33:14.280 María Angélica Madero There are ideas there of the imprint of the subject into the world that I really like about this project. So starting with a singular imprint of the fingertips by shaping something, in the act of translating, and in the act of writing. Taking that sort of radical agency of the subject into a collective sensemaking. And everyone being part of that distributed authorship or that distributed space. And being open to contradictions and being open to interpretations was also part of defining the method, which is paradoxical because methods are sort of non prescriptive algorithms or steps that you can take to find out something.

0:35:26.370 --> 0:35:26.560 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) One of the many things that is still open is how this method can be used for others in different places. How it can take place in all those factories of knowledge. And I think another thing that we have pending is a series of interviews to different people working on translation right now in different contexts in very different ways.

In the course of the project we found many others also interested in this, and it's something that we want to do to bring together through a collection of similar questions.

0:37:22.270 --> 0:37:38.30 María Angélica Madero I think it would be nice to finish this dialogue, maybe inviting everyone to be part of what we’re doing, as it’s not ours. It’s yours. Just do it. It's open source. Just go and use it, and try it out as a workshop or as a collective gathering, or as a way of learning, or teaching, or do it when you’re too lazy to teach a class.

(out of bounds automatic generated translation)

0:38:13.940 --> 0:38:14.770 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) List of joker.

OK, tenemos.

0:38:28.490 --> 0:38:29.400 María Angélica Madero Methoxsalen Mela.

JAMA ajjampur WhatsApp.

0:38:32.450 --> 0:38:34.820 Pinol Arevalo, S. (Santiago) The bodyguard, Dala.

Transcript.

After that, to put the stories and contributions together, participants were invited to collectively imagine the future of coliving within each of the categories and create a shared piece through lino-carving. In an unexpected parallel to many real living situations, the pieces of linoleum that we cut into many funny-shaped pieces, initially intending them to come back together into a neat rectangle, refused to form into such an orderly structure. Instead, the final lino-tapestry ended up taking a shape that none of us had planned or had full control over, making sense only as something collectively decided.

Through this shared visual imagination we hoped to create a starting point for new resistance in our everyday coliving realities.

Appendix 1

DECOLONIAL (RE)MEDIATORS

Un Manifiesto para Subtraducir

You should try talking in my shoes for a mile. —Sofia Vergara

No se pierde nada en la traducción. Siempre todo estaba perdido, mucho antes de que llegáramos. —A manifesto for Ultratranslation by Antena

Appendix 2

DECOLONIAL (RE)MEDIATORS

A Manifesto for Undertranslation

You should try talking in my shoes for a mile —Sofia Vergara Nothing is lost in translation.

Everything was always already lost, long before we arrived. —A manifesto for Ultratranslation by Antena

An intersemiotic translation is any form of translation that uses at least two different semiotic codes, such as the translation from words to images, to numerical codes, or to non-verbal sounds.

Knowledge is singular, when made into plural is not recognised by the text editor where this text was written

Netnography is an adaptation of ethnography for the online world. It’s also called Internet Ethnography.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fansub

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/45LlIho00aYuBVXo1UjYgo?si=89f307c30c564ece

https://antenaantena.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/ultratranslation_eng.pdf

María Angélica is getting rid of categories that limit her this year.

Santiago is an undisciplined artist who situates his practice on the coastline between art and education.