On a fresh spring afternoon in 2017, I met the artist Zoë Paul on the terrace of an Athenian café for an exchange of our artistic interests and practices. There she introduced me to the work of Masanobu Fukuoka (1913-2008), a Japanese microbiologist and farmer, who in the 1950s and 1960s developed what he called natural farming or do nothing farming (自然農法). His agrarian concept is based on a detailed observation of a local ecosystem, from bacteria to soil, plants, insects, animals, and even geology and climatic condition. Farming then happens through carefully moving the balance of said ecosystem towards the production of wished crops, all while maintaining the delicate relationships between zoologic, fungal, and plant beings. Contrary to what the term do nothing may imply, this method is laborious as farmers need to constantly watch that the ecosystem stays in balance and apply their deep knowledge of agrarian techniques. Due to the necessity of instantaneous reactions, Fukuoka considered human culture to be part of this methodology and implied its need for adaptation to the ecosystem. The do nothing refers to the restrain of human design within the system, as the farmer rather follows ecological cycles than adapting the ecosystem to human needs. In contrast do monoculture methods, which bulldoze local conditions until they fit the idea, natural farming is at its core decolonial and ecological, thanks to its reliance on naturally developed ecosystems within their locality.

Do Nothing Curating

Masanobu Fukuoka, Creative Commons

Paul went on to describe her reliance on these thoughts in developing her artistic practice that combines recuperated materials and traditional Greek crafts. In old wells and springs, she recycles wool, just like it was done for centuries, and weaves it into rusty refrigerator parts found in the streets of Athens. She also creates handmade pearl-curtains out of clay balls, all burned to different degrees and colours, with which she creates suspended, Hellenistic drawings. These works, and many more by her, are based on laborious processes and were historically done in groups (of women), but they differ blatantly from Fordist ideas of labour. Rather, the shared work offered a space of communion during which gossip and information were exchanged, as well as checked on the wellbeing of individuals and the community. The product carried thus much more than transactional value, but it was a representation of the very social fabric it was created in. It is work on multiple relationships.

These thoughts then inspired an inquiry into the sustainability of the fast-paced economy of aesthetic innovation within the art world: new works, younger artists, obscure discoveries, the art market never fails to deliver a new bit for consumption. The need to prevail within this attention market promotes digestible aesthetics instead of aesthetics that work within natural and social relationships. This is not solely the fault of a murky art market that only recently started to develop transparency, but of institutions and schools as well. Artists, students, curators do need to distinguish themselves through anticipating or even forming trends, presenting discoveries, etc. All in all, we are all nudged towards aesthetic "innovation" instead of adapting to social and environmental circumstances. The story of how an artist or an artwork came to where they now matter more than their workings in their environment. Entertainment prevails, negotiations disappear. Much later I found Ellen Dissanayake's work, in which she researches the role of art (or "making special", as she calls it) within the daily survival of early humans. Not surprisingly, she hypothesizes art as marking and addressing one's immediate environment, with all its dangers and rewards. The aesthetic form helps mediate the world and constructs it at the same time. It is not hard to draw a line from Dissanayake's theory to contemporary society and art. Even today we struggle with the question of how to witness the world and how that determines our relationship with the world. Though probably not so holistic anymore and rather according to our consumption behaviour. Digestible aesthetics mediate a digestible world. And a sustainable world is mediated through sustainable aesthetics.

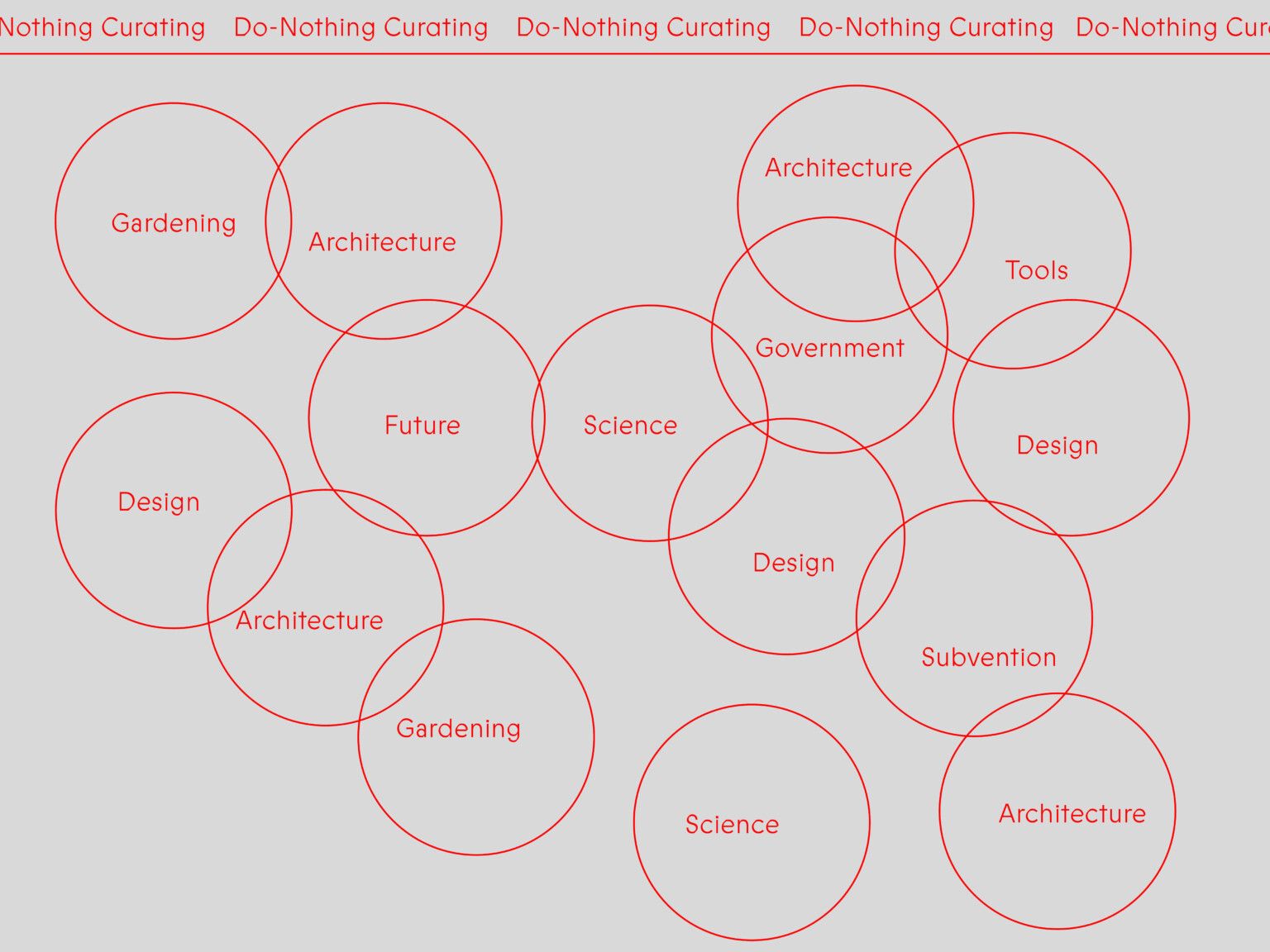

Just like Fukuoka proposed for agriculture, a sustainable model of culture could be based on the close observation of its ecology. But the challenge in determining all relevant factors is the unstable system of relevance; especially contemporary art typically oscillates between local scenes and internationalism. These changing points of view thus add to the difficulty of identifying relevant factors in assessing the art ecosystem. At this point Do Nothing Curating started to take shape, based on the question of how to gain sufficient knowledge on sustainability and culture. The issue lies in the many factors that need to be taken into account, of which locality is a critical one. Aside from personal relationships art is dependent on a multiplicity of factors, that are mutually impacted by the aesthetic forms themselves. Each artwork and its environment, even other artworks, are in a mutual, ecological relationship. This environment includes a vast number of disciplines and expertise which greatly surpasses the abilities of one human brain. Under normal academic circumstances, such an endeavour would be near impossible, so this needed its own approach.

At this point, I received the recommendation by a friend to rather collect the knowledge instead of synthesizing it. The advantage is clear; the expertise is already available; it just needs to be brought together. Reading stands at the core of the concept of the platform and was the main track in designing Do Nothing Curating and the website. It is the main medium of inquiry and observation of the environment as an aesthetic construction. As opposed to artworks of any form, the text can unravel and mediate the complexities contained within the aesthetic form without distracting the reader through the aesthetic experience. Within this project, the text does not create the experience of the environment but solely retell the experience. Additionally, it allows thinking of intertextual relationships as an episteme for environmental knowledge for our future. Here, I speak of intertextual relationships not in the sense of a genealogy of ideas but as an ecology of knowledge. The platform should not just serve as a repository of contributions that are distinguished between recent and old but rather encourage amplifying the impression of the world by reading contributions from different points in time and space. Older texts may still hold the potential to contribute to ongoing debates despite disappearing behind newer insights. For this reason, Do Nothing Curating is thought to reactivate contributions and accept pre-existing contributions.

A major concern remained the realisation of a sustainable world, nonetheless. Texts contribute only so far to the construction of aesthetic experiences. Much like a garden, fruits from this ecology of knowledge may be reaped from time to time. The reading experience is thought to inspire new aesthetic experiences of a sustainable world. This is how Do Nothing Curating aims at the global transformation of the currently exploitative relationship between humans and the environment towards a sustainable one; by inspiring the imagination needed to imagine oneself in such a place. Whether this happens through a new contribution to the platform or by projects independent from this initiative, the platform should offer an environment of inspiration.

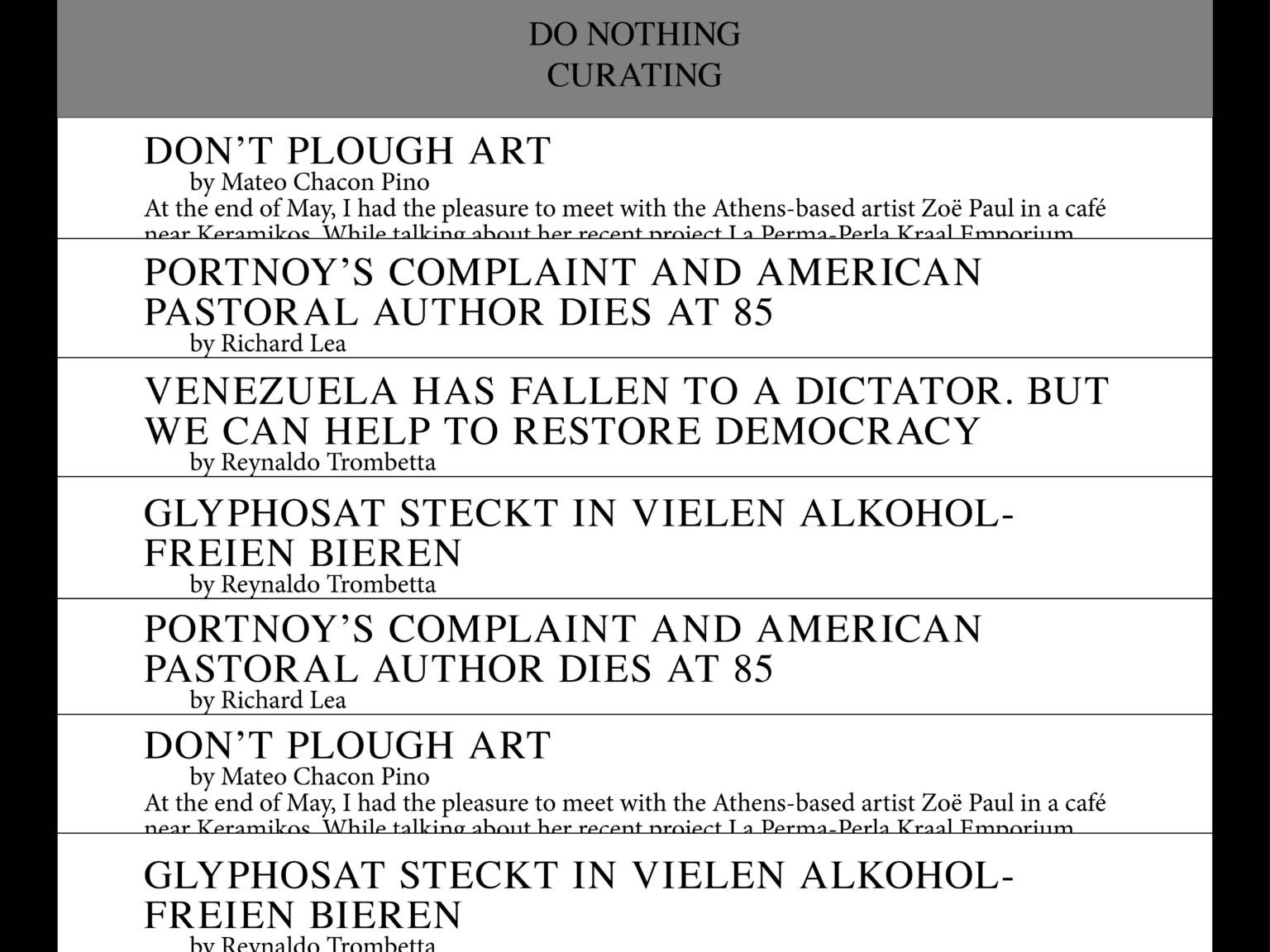

With these ideas in mind the graphic design collective HO-MI, Christian Hofer and Lea Michel, set forth to develop the digital platform for Do Nothing Curating in collaboration with web designer Joseph Kennedy. As inspiration may arise spontaneously and without formal interference, the team focused on two pillars: reading and navigation of the website. The former was interpreted as the goal of a readable presentation of longer texts. This was embodied by a simple design in three colours and a clear layout. HO-MI took inspiration from 20th-century Italian sports gazettes that used to be printed on thin, pink paper. These outlets retold the story of football matches or other athletic events only by text and without accompanying images. The fixed width of the text columns and calm background of the website make reading on different devices (mobile and desktop) equally easy while menu-buttons remain accessible at the borders of the screen. Readers can scroll through the text without being interrupted by images or other aesthetic interventions.

Even before visitors to the website arrive at a text to read, they experience the episteme of the website on the homepage; four random texts are presented in a simple grid upon reaching the platform. By clicking on a centred button, readers can refresh the selection and trigger a new set of four random contributions. With this feature, the website keeps older contributions from being buried behind dozens of pages of newer texts as it may happen with traditional blogging-formats. Nevertheless, the website offers a toggle for a chronological display as well as for search by keywords or full text.

Early Design Sketches, HO-MI www.ho-mi.ch

Do Nothing Curating started publishing in early 2020 as a LEARN at the School of Commons, a platform for self-organized learning and researching at the Zurich Art University ZHdK. This collaboration was the main driver of the activities on and by the platform throughout this year of the pandemic and characterised by questions on archival methods of research and the access of the public to knowledge. An under-discussed aspect remained the editorial aspect, even as Do Nothing Curating commissioned several new contributions, some of which are still to be published. The contributors come from a variety of backgrounds which can be summarized as artists, researchers, and curators.

The range of insights spanned from a description of studio practices with spiders to essays on the metaphorical potential of beehives to the intersection of environmental and indigenous struggle in South America. Each text was written from the author's point of view and methodological framework, proving that various forms of research, artistic, scientific, or philosophical, generate equally valid observations of our relationship to the world. More so, formal rigour showed to be of different characteristics according to the discipline. But the worldbuilding potential of imagination that all contributions showed convinces that a sustainable human existence is possible and within reach.

With this imagination, it was possible to organize several events throughout the year with the School of Commons. A first reaction to the pandemic in early 2020 was an online talk to discuss the strain of lockdowns on environmental projects within the arts with curator Àngels Miralda and artist Matthew C. Wilson. Even before the first outlets jumped on the economic impact the lockdown has had on local art communities, this conversation highlighted how current funding systems were not working as a supporting structure. Rather, it came out, they reinforced market-driven work environments, that artificially maintain a state of precarity in the art world.

In mid-2020, Do Nothing Curating participated in the "Hope Springs Eternal" exhibition organized by Second Nature Design Projects. While the exhibition itself marked the end of a temporary studio building in central Zurich, the platform contributed with a showcase of Venezuelan video artists in collaboration with the artist Ana Alenso. Paralleling the multiple epistemes included in Do Nothing Curating, this showcase brought together video-works on urbanistic research, an artistic depiction of the historic oil market, and a performative poem on the social underbelly of Caracas. The connecting thread was the impact of the nationalised oil industry on everyday life.

Érika Ordosgoitti, corra, 2014, spoken word poetry, 8 min. 2 sec., screengrab

Another event was the commission of a new performance by Mapuche artist Paula Baeza Pailamilla, who managed to enter Switzerland against all odds. After participating in the Berlin Biennial, she spent a few weeks in Zurich to research and develop an artwork based on the migratory nature of plants. A great source of inspiration was the old botanical garden of Zurich, where a variety of non-native plants are exhibited under the sky. What looks like a lush garden from outside is in reality an unnatural exhibit of plant species from opposite parts of the world. Unlike a natural garden, these plants are cared for to keep them from spreading further as the gardeners intend them to. Additionally, this research looked into the language used in local environmental policy aimed at neophytes. These non-native plants arrived in Switzerland through different means but effect all a dramatic change in local biodiversity and ecosystems. This language is characterized by a martial vocabulary, that eerily resembles how migrants have been treated in the Swiss context. These two findings came to be the base for the performance, which consisted of releasing the non-native plants in a loving gesture into the river Sihl to migrate wherever the flow takes them.

Paula Baeza Pailamilla, ANÜMN, 2020, performance, photo: Jonathan Ospina

Do Nothing Curating proved itself at the School of Commons as a working concept. Some editorial processes need refinement, as does the communication of events. Nonetheless, the platform is shaping the discourse of sustainability in the arts. In a way, this project serves as meta-research and as meta-art-production. Its importance lies in the continuous growth of knowledge, as it is not finished at some point. Rather, I would like to see it transform and become alive by itself. The yearlong collaboration with the School of Commons proved the value such a project has, as it offers many uses by readers and contributors alike. In the future, it should see more ongoing projects and regular contributions to sow imagination further and generate even more fruits to reap.

Mateo Chacon-Pino

Mateo is a Colombian-Swiss art historian and curator.